|

Case

study 3

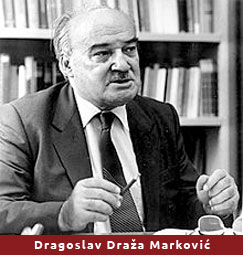

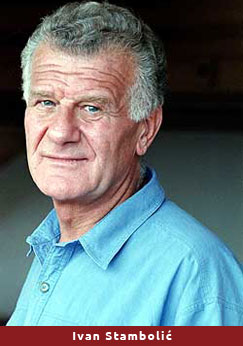

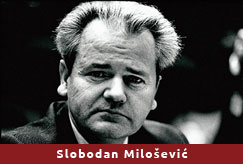

In her books,

Sabrina P. Ramet used the terms

“recentralization” and

“recentralists” to designate the

efforts to restrengthen the powers

of the federal state and the

proponents of such politics in

Yugoslavia during the 1980s1. She

used the term “recentralization” in

that specific meaning to define the

political programme of the most

prominent Serbian politicians,

Dragoslav Draža Marković, Ivan

Stambolić and Slobodan Milošević. On

the trail of this terminology I have

carried out preliminary research

which points to a significant

concurrence of the views of these

politicians about the importance and

role of the federal state within the

Socialist Federal Republic of

Yugoslavia (SFRY). Their recentrist

efforts at the federal level were

also accompanied by the persistent

efforts to reduce the degree of

autonomy enjoyed by the provinces.

In this article, the term

“recentrist” will be used in this

complementary meaning or, in other

words, it will imply the

recentralist efforts both at the

level of SR Serbia and the SFRY

level. In socialist Yugoslavia, the

proponents of the mentioned

political programme were called

“centralists” or, perojatively,

“unitarists” in order to link them

to the discarded ideology from the

time of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

It seems to me that “recentralism”

is a more precise term for defining

the ideology and political concepts

of the mentioned politicians during

the 1970s and 1980s, since it points

to the process of renewed

centralization, namely a return to

the relations prevailing before

Aleksandar Ranković's removal from

office and the adoption of the

constitutional amendments of

1967-1971.

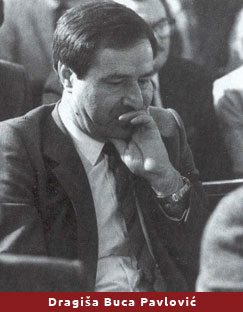

After my

subsequent research into the public

discourse and writings of Dragiša

Buca Pavlović I have decided to

include him in this specific Serbian

school of recentralism. The subject

of this research is devoted to the

public discourse and political

efforts of the four mentioned

politicians. The evolution of their

recentralist concepts will be

perceived on the basis of their

synchronous and diachronous

comparisons in the time period from

the adoption of the first

constitutional amendments

(1967-1971) to the so-called “years

of the solution“ of the Yugoslav

crisis (1987-1990). A special

problem-related aspect of this

article will involve the question of

the framework and extent to which

the recentralist efforts can be

considered as a legitimate demand

for the rearrangement of relations

in the common state and the extent

to which they turned into an

obstacle to the survival of the

common state?

In order to answer

the above question it will first be

necessary to determine the

foundation on which the balance of

the system enabling the survival of

the Yugoslav federation was laid.

This problem will be addressed in

the section following the

introductory part of the article.

The recentralist efforts of

Marković, Stambolić, Pavlović and

Milošević will be analyzed in the

subsequent four sections. The

results of this research and

comparative analyses and conclusions

will be presented in the last, sixth

section. The article is based on the

accessible archival materials in the

Serbian Archives, memoirs and print

media.

Federal Yugoslavia as a “Balance of

Power” System

The thesis about

the Yugoslav federation as the

“balance of power” has been

developed by Sabrina P. Ramet in her

book dedicated to the phenomena of

nationalism and federalism in

socialist Yugoslavia2. According to

this thesis, after the death of the

President of the Presidency of the

SFRY, Josip Broz Tito, the Yugoslav

federation was maintained within the

framework of the system of complex

federal institutions, based on the

consensus principle or, more

precisely, the political will of the

representatives of six federal units

and two provinces, which were

considered the “elements of the

federation” in federal bodies.

Before reaching a consensus the

representatives of the federal units

had to carry out long negotiations

and “harmonize” their views.

Conflicting regional interests and

different short-term “coalitions”

formed by the federal units would

come to the surface just during the

decision-making process.

The

representatives of the republics,

which otherwise had different views

on some issues, supported the

proposed solutions on a case-to-case

basis. Although the opinion prevails

that there was an insurmountable gap

between the political concepts of

the Serbian and Slovenian

leaderships, the two republics still

acted solidarily when some decisions

had to be made. This happened, for

example, when the decisions on the

appropriation of funds for the

underdeveloped Yugoslav regions had

to be made.3 It was probably just due

to the mentioned short-term

coalitions of the federal units that

the relative stability of the system

and “balance of power” within it

were maintained until Slobodan

Milošević came to the foreground of

the Serbian political scene.

In a systemic

sense, however, the greatest

challenges to the institutional

balance, established by the

Constitution of 1974, were still

coming from the ranks of top-level

Serbian and Slovenian party and

state officials. As for the Serbian

side, they included permanent

initiatives for a reduction of the

competences of the autonomous

provinces and recentralization of

federal institutions. As for the

Slovenian side, however, there was a

tendency towards the greater

decentralization of Yugoslavia's

political and state system. The

official demands of some Serbian

politicians for the rearrangement of

relations within the federation and

SR Serbia already date from the time

of the adoption of the first

constitutional amendments of

1968-1971. After the removal of

Marko Nikezić and Latinka Perović

from the Serbian leadership in

October 1972, these efforts became

some kind of SR Serbia's official

programme. In other words, a more or

less constant clash between the

conflicting concepts or, at least,

pronounced discontent with the

existing situation among the Serbian

political elite continued in the

SFRY throughout the period

1968-1990.

In this article,

the “harmonization system“ and

principle of maintaining the

“balance of power“ among the federal

units in federal bodies were adopted

as vital prerequisites for the

survival of the common state.

Everything that could bring these

prerequisites into question was

considered a potential danger to the

system. Proceeding from this

premise, the analysis of the

recentralist concepts of Serbian

politicians will be especially

focused on this aspect. The

outvoting effiorts could create

suspicion among the republics

fearing that they could remain in

the minority. Unilateral actions

taken without prior agreement among

the federal representatives could

also affect the balance of power

within the system and keeping the

federal units together.

The main criterion

for assessing the political

influence and contribution of the

Serbian recentralists will be their

contribution to the preservation of

federal institutions. In this

article, I will try to analyze in

what domain the development of

recentralist concepts could lead the

country to its collapse and to what

extent it represented the justified

demand for a change in the

federal-state relations which was

made by one federal unit.

Dragoslav Draža Marković

The present

perception of Draža Marković's role

in the political life of socialist

Yugoslavia and the initial steps of

Milošević's takeover of power is

mostly positive. This was

contributed by his resolute

opposition to Milošević's candidacy

for the leader of the Serbian party

and Milošević's politics, later on.

Marković's bitter opposition to

Milošević is also found in his

memoir published in 2010.4 Ivan

Stambolić also spoke about Marković

with a lot of sympathy. He praised

his wisdom and insightfulness (“an

old fox“) in voicing opposition to

Milošević's candidacy for the leader

of the Serbian party in 1986.5 Today,

Marković's political role is mostly

considered constructive and the

opposite of Serbia's politics

pursued after the Eighth Session of

the Central Committee of the League

of Communists of Serbia (September

1987). The present

perception of Draža Marković's role

in the political life of socialist

Yugoslavia and the initial steps of

Milošević's takeover of power is

mostly positive. This was

contributed by his resolute

opposition to Milošević's candidacy

for the leader of the Serbian party

and Milošević's politics, later on.

Marković's bitter opposition to

Milošević is also found in his

memoir published in 2010.4 Ivan

Stambolić also spoke about Marković

with a lot of sympathy. He praised

his wisdom and insightfulness (“an

old fox“) in voicing opposition to

Milošević's candidacy for the leader

of the Serbian party in 1986.5 Today,

Marković's political role is mostly

considered constructive and the

opposite of Serbia's politics

pursued after the Eighth Session of

the Central Committee of the League

of Communists of Serbia (September

1987).

In contrast to

this affirmative judgement about

Marković's political legacy, we have

obtained completely different

coordinates for his political

biography from his contemporaries

and his memoir. Marković's

contemporary Raif Dizdarević, one of

the leaders of Bosnia and

Herzegovina and later the top-level

federal official, says in his memoir

that Marković had a “reputation as a

nationalistically coloured Serbian

politician“ and that he was “often

[labelled as] the bearer of Greater

Serbian tendencies“.6 In his memoir,

Marković himself reveals that he is

aware that as early as the 1970s he

was considered a “unitarist“ and

“Greater Serbian centralist“ in the

Yugoslav circles.7 By his own

admission, the leaders of Kosovo and

Bosnia and Herzergovina considered

him “Ranković's supporter“ or worse

“than Ranković himself” due to his

advocacy of “the authoritative

bodies within the Federation”.8

Latinka Perović,

Marković's contemporary from the

political opposition camp, does not

miss an opportunity to express

strong criticism of his political

concepts, despite trying to present

a balanced portrait of him in her

works. As for the Kosovo problem,

she argues that there are no

principled differences between his

views and those of Dobrica Ćosić.9

Thus, she holds that his national

sentiments about this problem are so

strong that he can be considered

equal to the most prominent Serbian

nationalist of the time. In her

opinion, there were no essential

differences between nationalism in

the party circles and that outside

of them. Perović is also convinced

that the armed conflicts of the

1990s resulted necessarily from the

common “logic“ of the concepts of

Dobrica Ćosić and Draža Marković

about the rearrangement of the

relations within the Federation and

resolution of the Kosovo problem.

Consequently, regardless of

Marković's bitter opposition to

Milošević's rise to power, he bears

the responsibility for advocating

the concepts that were burdening the

relations within Yugoslavia for

decades.10

Due to significant

differences of opinion about Draža

Marković's political legacy and role

in the process of aggravating the

Yugoslav crisis, an analysis of his

public discourse and the evolution

of his political concepts is of

greatest relevance for dealing with

the questions raised in this essay.

Rethinking the political genesis of

Marković's (re)centralism will begin

with his stance on the adoption of

the constitutional amendments of

1967-1971. Thereafter, the analysis

will be focused on the events

associated with the debates prompted

by the appearance of the so-called

Blue Book in 1977 and the subsequent

evolution of his concepts during the

1980s, marked by a political and

economic crisis.

The first

indications of Marković's

recentralist concepts already

emerged in the first part of the

process involving the adoption of

the amendments of 1967-1969. In

their developed form, the

formulation of these concepts can be

followed in his diary notes written

from December 1970 to May 1971. In

their complete form they were

presented in the exhaustive

interview given by Marković in his

capacity as President of the

Assembly of SR Serbia for Belgrade's

daily newspaper Politika in late

February 1971.11 His recentralism

refers to (1) the proposals for

changing the structure of decision

making in federal bodies and (2)

reconsideration of the

constitutional and legal status of

the provinces forming part of the

Yugoslav federation. These are the

two most frequent themes dealing

with internal political relations in

Marković's diary.

At the time of the

harmonization of the constitutional

amendments (1968-1971), Draža

Marković's recentralist tendencies

referred to the principled demands

that federal bodies should enjoy

full capacity necessary for the

exercise of their functions.

Consequently, he allegedly does not

oppose the reduction of the powers

of the Federation, but holds that

the remaining powers should be

efficiently exercised. In his

interview for Politika, Marković

also says that efficiency in federal

decision making excludes the use of

veto power by the republics,

implementation of an inter-republic

consensus mechanism and

harmonization of each decision. In

his diary note of 5 December 1970,

he also raises the question of

alleged outvoting of which he was

accused by other republics.

“In

recent times, as far as equality is

concerned, the antivoting principle

has often been emphasized not only

in the context of the demands for a

parity composition of some bodies

or, in other words, the demands for

their composition based on

proportional representation (which

depends on their character and

competences), as well as the views

against majority decision making,

against 'outvoting' ... How to make

decisions in that case? Isn't

decision making by majority voting

still the most democratic

decision-making method? In some

cases, the procedure may demand not

only a simple majority, but also a

two-thirds majority and the like. In

any case, however, voting must

remain the method of making a final

decision“.12

In order to

confirm the correctness of his

principled view, Marković also

mentions the conversation of the

country's top officials during their

visit to Romania in November 1971.

On that occasion, Džemal Bijedić

allegedly said in Tito's presence

that he would not have voted in

favour of the voting power of

federal bodies had he known that he

would become the head of government.

Marković told him that he was

against this principle, alhough he

knew that he would not be the head

of government.13 Until the end of

Marković's active involvement in

politics, his political activity

included the efforts towards

increasing the efficiency of federal

bodies, and resistance to the

excessive implementation of the

principle of inter-republic

harmonization.

Apart from the

principled comments on the

inefficiency of federal

institutions, in Marković’s diary

one often comes upon his exclusively

Serbian ethnic reasoning. So, he

ponders over the extent of Serbian

discontent with the constitutional

amendments. At one point he wonders

whether “it is in the interest of SR

Serbia and the Serbian people to

live in such a Yugoslav state which

they wish to create?”14 It seems that

the political elite in Serbia under

Ranković and after his demise

developed a political culture that

continuously supported the idea of

(re)centralism as the only framework

within which the idea of a common

state was possible.15 The

Nikezić-Perović political tandem

represents the only discontinuity

and short-lived departure from such

a political culture and such

political concepts in Serbia.16

In the postwar

period, the Serbian and Yugoslav

communists were distinctly critical

of the centralist and unitarist

concepts of Aleksandar

Karadjordjević and Serbian bourgeois

political parties in interwar

Yugoslavia. After the Brioni Plenum,

the seal of unitarism was clearly

imprinted on the dominant political

culture in Serbia, which was formed

under Aleksandar Ranković's

influence. Draža Marković was aware

of the fact that his political views

were also perceived in such a

perspective of the long duration of

Serbia's 20th century politics. In

his notes he rejects this “imposed”

complex and efforts to burden the

current Serbian politics with such

an “ancestral sin“ of their “Greater

Serbian fathers”.17

Judging by the

frequency of his writing about this

issue during the period 1968-1971,

Marković was mostly preoccupied with

the process of emancipation of the

provinces. Moreover, his critical

observations about the provincial

officials and symbolic status of the

autonomous provinces are so often

found in his diary that his attitude

towards them assumed the proportions

of a personal obsession. The

Albanians are persistently called

“Šiptari”, although this name was

considered derogatory and removed

from official phraseology before

these notes were written. Some

comments reveal a great deal of

suspicion towards the provinces and,

in particular, Kosovo's officials.18

His discontent with a lenient policy

towards the provinces is also one of

his principled criticisms addressed

to Nikezić and Perović at the time

of the escalation of their conflict19.

In the mentioned

interview with Politika in March

1971, Marković expressed significant

reservations about the emancipation

of the provinces and their promotion

into almost equal constituents of

the Yugoslav federation. Allegedly,

he does not oppose the further

increase of autonomous rights at the

provincial level, which can be

viewed in the context of the general

process of deetatization. However,

he holds that this process should be

regulated by the relevant changes in

the republican constitution. In this

way, the problem related to the

scope of provincial autonomy would

be resolved in the context of the

arrangement of relations within SR

Serbia and not by decisions imposed

from outside. With the exception of

this clear critical stance on

inteference in the relations within

the republic, his interview with

Politika mostly reveals his doubts

and reservations about these issues.

The only true criticism of the

constitutional amendments can be

found in his diary notes. As for the

status of the autonomous provinces,

Marković is actually bothered by the

essential and protocol problems. He

writes that during Tito's visit to

Kosovo in 1971 he did not notice any

flag of the Republic of Serbia.20 In

addition, not one representative of

the Republic of Serbia was invited

to attend the ceremonial session

dedicated to the proclamation of the

Constitution of the Autonomous

Province of Kosovo on 27 February

1974.21 Here is how Marković sees the

protocol imposed by the provincial

authorities during Tito's visit to

Kosovo in April 1975: In the mentioned

interview with Politika in March

1971, Marković expressed significant

reservations about the emancipation

of the provinces and their promotion

into almost equal constituents of

the Yugoslav federation. Allegedly,

he does not oppose the further

increase of autonomous rights at the

provincial level, which can be

viewed in the context of the general

process of deetatization. However,

he holds that this process should be

regulated by the relevant changes in

the republican constitution. In this

way, the problem related to the

scope of provincial autonomy would

be resolved in the context of the

arrangement of relations within SR

Serbia and not by decisions imposed

from outside. With the exception of

this clear critical stance on

inteference in the relations within

the republic, his interview with

Politika mostly reveals his doubts

and reservations about these issues.

The only true criticism of the

constitutional amendments can be

found in his diary notes. As for the

status of the autonomous provinces,

Marković is actually bothered by the

essential and protocol problems. He

writes that during Tito's visit to

Kosovo in 1971 he did not notice any

flag of the Republic of Serbia.20 In

addition, not one representative of

the Republic of Serbia was invited

to attend the ceremonial session

dedicated to the proclamation of the

Constitution of the Autonomous

Province of Kosovo on 27 February

1974.21 Here is how Marković sees the

protocol imposed by the provincial

authorities during Tito's visit to

Kosovo in April 1975:

“Throughout that time they were

occupied with how to leave the

impression that are were fully

autonomous and that everything seems

as if there is a direct relationship

between Kosovo and the SFRY. In this

context, M. Bakalli's otherwise

absurd and funny demand to inspect

an honour guard together with the

President is characteristic. They

are completely obsessed with

statehood. How hard it is for them

to say “SR Serbia” and express their

belonging to SR Serbia. With their

emphasized, even overemphasized

'Yugoslavism' and commitment to the

SFRY, Tito and LCY, they try to blur

the fact that the autonomous

provinces 'form part of SR Serbia'”.22

The work on the

Blue Book and its presentation at

closed party forums in early 1977

reflect the culmination of

Marković's frustrations with the

constitutional and legal status of

the Serbian provinces. This internal

document, whose preparation was

commissioned by the Presidency of SR

Serbia (headed by Marković) in 1976,

reveals the illogicalities and

contradictions concerning the scope

of provincial and republican

competences within SR Serbia. In the

case of the Assembly of SR Serbia,

the authors of the Blue Book find it

problematic that its legislative

activity is almost exclusively

confined to the territory of

so-called Serbia proper and that the

provincial delegates also

participate in its composition and

bodies. However, they are the

delegates of the regions of the

republic “whose problems, as a rule,

are not addressed in the republican

assembly“. Under such circumstances,

it is difficult for these delegates

“not to feel estranged from their

own delegate base“. The authors of

the Blue Book hold that “at this

point the entire delegate system

begins to lose its real sense”.23 In

almost the same critical way the

authors of the Blue Book comment on

the scope of powers exercised by the

Presidency of Serbia, which is

confined to Serbia proper and whose

composition also includes provincial

officials24.

As for the

Republican Executive Council and

other republican bodies, the authors

of the Blue Book conclude that,

despite the constitutional

defiunition of SR Serbia as a state,

they do not exercise their powers in

the autonomous provinces.25 This

problematizes both the

constitutional and legal status of

Serbia and the proclaimed equality

of the Serbian people in the

Yugoslav community. Here is how this

question was raised in the Blue

Book:

“Considering the pronounced

tendencies towards weakening the

unity of the Republic as a whole and

increasingly distinct

differentiation of three separate

regions, loosely or only formally

interconnected, the question that

imposes itself is whether the

Serbian people – on terms of

equality with other Yugoslav peoples

– exercises its historical right to

a nation state within the Yugoslav

federation, which is based on the

principle of national

self-determination.”26

This argumentation

is additionally deepened by the fact

that the territory of Serbia proper,

as the only territory where the

powers of the Republic are

exercised, was not adequately

defined in a legal or

socio-political sense. The authors

of the Blue Book hold that this is

another reason leading to the

“political inequality of working

people and citizens from the

narrower territory of the Republic”.27

Consequently, this internal document

pointed most directly to the defects

in the statehood of SR Serbia and

alleged inequality of the Serbian

people in the system of

institutions, formed under the

constitutional amendments and

constitution of 1974. In the face of

significant opposition in the

republic and at the federal level,

the debate about the Blue Book was

put ad acta by the end of June. As

Marković concludes, the debate

“ended by taking a `Solomonic`

stance as if the Blue Book does not

exist”.28

In his diary note

of 29 June 1977, Marković emphasizes

the significance of the Blue Book

because it pointed to significant

constitutional, legal and state

problems: “The problem was opened in

Tito's time. It is now being

discussed.”29 In these two sentences,

perhaps even inadvertently, the

author compromised the form of

diary, in which one keeps an

authentic daily record of events and

does not mention some later events,

based on one's subsequent

experience. It is evident that the

diary note of June 1977 was added

later on, certainly after Tito's

death. Un view of this fact, one can

only speculate what other additions

were made to these “diary” notes.30

From 1978 to 1982,

Draža Marković was the President of

the Federal Assembly and then the

President of the Central Committee

of the LCY. At the Fourteenth

Session of the Central Committee of

the LCY, in October 1984, he came

forward as a prominent advocate of

the recentralist rearrangement of

the country. His speech and exchange

of retorts with his Slovenian

colleagues Andrej Marinc and France

Popit summarize and fuly develop his

views on the improvement of the

efficiency of federal bodies. His

retorts were prompted by Marinc's

negative comments on the first draft

of changes to the long-term

stabilization programme prepared by

Serbia, and the interview given by

Borislav Srebrić, Vice-President of

the Federal Executive Council, for

the Sunday edition of Borba ten or

so days before the session of the

Central Committee of the LCY. The

mentioned first draft demands

greater powers for federal bodies,

while Srebrić, in his interview,

criticizes the widely used consensus

principle in federal decision

making.31

In his interview,

Srebrić explained the technical

problems encountered by the federal

authorities in their efforts to be

efficient given the burden of

“harmonization” preceeding every

operational decision making.

Consensus is also problematized not

only as a burden in the

decision-making process, but also as

something being essentially contrary

to the democratic principles: “The

question that imposes itself here is

whether consensus is a democratic or

antidemocratic form due to outvoting

the minority”.32 Such reasoning could

not be more congruent with the

concepts advocated and developed by

Draža Marković during the previous

fifteen years. At the session of the

Central Committee of the LCY, the

consensus problem gave him an

opportunity to summarize his

recentralist arguments once again in

his polemic with the Slovenian

representatives.

The most original

part of Marković's argumentation

involved arguing that insistence on

census-based decision making was

actually unconstitutional. According

to Marković, the authors of the 1974

constitution anticipated the

consensus process for a limited

number of issues of general

importance and not for making all

decisions at all federal levels.

Such a use of consensus turned into

its opposite:

“[...] one good principle, which

should guarantee equality and

protect certain interests, was

extended and turned into its

opposite. We have an opposite effect

because we wanted to be `more

constitutional` than anticipated

under the Constitution, ‘more equal’

than written in the Constitution and

‘more democratic’ than we agreed

upon [...] because we extend the

equality issue beyond the

Constitution. [...] We criticize the

Federal Executive Council for its

indecisiveness and failure to come

up with proposals. The Federal

Executive Council acts tacitly

according to the unanimity

principle, contrary to the

Constitution. This is the best

example of how acting beyond the

Constitution is as unconstitutional

as acting less than anticipated

under the Constitution33.

As for the

“democratic spirit” of the

implementation of the consensus

principle, Marković's reasoning is

identical with that of Srebrić.

Majority vote decision making which

is, in Marković's opinion, “most

democratic”, became so undesirable

in Yugoslav institutions that it was

pejoratively called “outvoting“.

Under conditions of economic crisis,

which was deepening the gap between

rich Slovenia and the less developed

southern republics, it seems that

Marković and other Serbian officials

were convinced that they could win

support for a more efficient federal

intervention from the less developed

ones. This issue will be dealt with

in more detail in the subsequent

part of this article.

Ivan Stambolić

Throughout his

active involvement in politics, when

he exercised party and state

functions, Ivan Stambolić advocated

recentralist ideas with respect to

both the status of the autonomous

provinces and relations within the

Federation. This conclusion imposes

itself even after a superficial

insight into the contents of his

public speeches and interviews in

the media during the period

1981-1987. Should we analyze the

frequency and intensity of his

advocacy of these views, they could

be associated with some concrete

phenomena and events in the society.

Namely, Stambolić took a harder line

on Kosovo and the provinces in

general as a response to the 1981

protests in Kosovo. Throughout his

active involvement in politics, when

he exercised party and state

functions, Ivan Stambolić advocated

recentralist ideas with respect to

both the status of the autonomous

provinces and relations within the

Federation. This conclusion imposes

itself even after a superficial

insight into the contents of his

public speeches and interviews in

the media during the period

1981-1987. Should we analyze the

frequency and intensity of his

advocacy of these views, they could

be associated with some concrete

phenomena and events in the society.

Namely, Stambolić took a harder line

on Kosovo and the provinces in

general as a response to the 1981

protests in Kosovo.

Tito's death and

the overtly hostile character of the

Kosovo protests finally provided

scope for republican officials to

reconisder the status of the

provinces. Ivan Stambolić also

testified quite unambiguously about

this issue in his “answers” to the

questions of journalist Slobodan

Inić. In this text of a memoir

genre, published in 1995, Stambolić

directly related the gradual

strengthening of Serbia's position

in Yugoslavia's internal politics to

Tito's death and the 1981 protests

in Kosovo.34 In his memoir, Raif

Dizdarević also holds that the

Kosovo revolt served as a trigger

for the Serbian leaders to take a

more resolute stance at the federal

level.35

On the other hand,

Stambolić's calls for a more

efficient federal intervention and

change in the relations within the

Federation became more frequent

since September 1984, when the

Federal Institute for Social

Planning revealed the data showing

that the economic growth of

so-called Serbia proper was lagging

behind other Yugoslav republics in

relative terms.36 From that moment

until the discontinuation of the

functions of the federal state, the

top Serbian officials were almost

unanimous in their calls for the

recentralization of federal

institutions. In this part of the

article we will first analyze

Stambolić's political views and

decisions concerning the autonomous

provinces and then his efforts to

strengthen the influence of federal

bodies.

Stambolić's speech

at the session of the Central

Committee of the LCS on 6 May 1981,

in the aftermath of the Albanian

revolt in Kosovo, was completely in

the spirit of proving the

correctness of the politics towards

the provinces, which was advocated

by the authors of the Blue Book.37 It

is probable that he also

persistently referred to 1977

because he wished to avoid

insistence on 1974, which would

imply the reconsideration of the

constitution itself. In Stambolić's

speech there is also a taste of

bitterness due to the leniency of

the then Serbian leaders who failed

to persist in getting to the bottom

of the provincial problems.

Stambolić is openly critical of the

then compromise involving doing

nothing about the autonomy of the

provinces. He views it as the

acceptance of an “illusion” that

something was agreed upon. In his

speech, he referred even four times

to “several months of debating in

1977”:

“When

we were considering the causes and

effects of the 1981 events in Kosovo

at the joint session of the

Presidencies of the Central

Committee of the LCS and SR Serbia,

which was convened these days,

Comrade Minić pleaded for `putting

those problems on the agenda as they

are so as to perceive their essence

and undertake to resolve them`.

However, the debates conducted in

1977 took the opposite course – some

comrades wanted to resolve the

problems without clarifying their

essence. […] At that time, we failed

to say clearly and resolutely that

SAP Vojvodina and SAP Kosovo had

their republic, their state union –

SR Serbia.”38

In this speech,

Stambolić was very critical of the

period of developing the relations

with the provinces from 1977

onwards, which was marked by their

significant estrangement. He argues

that in 1981, the Republic of Serbia

cooperated more successfully with

other Yugoslav republics than with

its own provinces. One can observe

the influence of the analyses

contained in the Blue Book in

Stambolić's highlighting the

illogicalities of the delegate

system under which the provincial

delegates and officials also

participate in solving all political

and economic problems of so-called

Serbia proper, while republican

officials rarely have a chance to

visit any of the two provinces.

Stambolić's suggestive tone seems to

imply that things must return to the

year 1977 and that Serbia's

arguments and principledness must

now be at a much higher level.

The tone of

Stambolić's speech at the session of

the Central Committee of the LCS,

held in December 1981, was similar.39

He referred a few times to 1977 as a

turning point in the politics

towards the provinces. Stambolić

speaks more specifically about the

“great responsibility” of the

Serbian leadership (“our great

responsibility”) for the wrong

assessment of the constitutional and

legal status of the provinces. He

adds that the attempt to raise a

counterrevolution in Kosovo in 1981

would not have been a surprise for

the Serbian leadership if the

mentioned assessments made in 1977

had not been so wrong. Stambolić

also calls for the unity of the

Republic and strongly condemns the

manifestations of separatism among

the Kosovo and Vojvodina

leaderships. In an indirect way he

also points out that in the period

after Tito's and Kardelj's deaths it

is necessary to find new solutions

for the provinces.40

Otherwise, in the

already mentioned book Put u bespuće

(Road to Nowhere), Stambolić, like

Draža Marković, showed a significant

degree of frustration over the

formal protocol and procedural

issues in Kosovo. He writes that the

visits of republican officials were

preceded by long negotiations as if

it was the question of inter-state

relations. Stambolić was also

embittered by the fact that at

provincial meetings which he

attended as the top republican

official, that is, the President of

the Presidency of the Republic of

Serbia, he was formally greeted at

the very end of the protocol list,

“after the last provincial official

in the list”.41 Like Draža Marković,

Stambolić's political biography from

the period 1981-1986 shows that he

was also occupied to a significant

extent with the status of the

provinces within SR Serbia. Otherwise, in the

already mentioned book Put u bespuće

(Road to Nowhere), Stambolić, like

Draža Marković, showed a significant

degree of frustration over the

formal protocol and procedural

issues in Kosovo. He writes that the

visits of republican officials were

preceded by long negotiations as if

it was the question of inter-state

relations. Stambolić was also

embittered by the fact that at

provincial meetings which he

attended as the top republican

official, that is, the President of

the Presidency of the Republic of

Serbia, he was formally greeted at

the very end of the protocol list,

“after the last provincial official

in the list”.41 Like Draža Marković,

Stambolić's political biography from

the period 1981-1986 shows that he

was also occupied to a significant

extent with the status of the

provinces within SR Serbia.

The issue

concerning the autonomous provinces

was unavoidably brought up at the

18th Session of the Central

Committee of the LCS, which was held

in November 1984. In his speech,

Stambolić insisted again on a “more

complete constitution of SR Serbia

as a republic”. His logic was

simple. Namely, what contributes to

the strengthening of one republic

also contributes to the

strengthening of the SFRY. His

well-known metaphor about

“co-tenants and subtenants” was also

recorded at this session. This

metaphor emphasizes quite clearly

that the provinces cannot be

subordinated to the republic, not

can they be equal with it:

“The

Socialist Autonomous Provinces and

nationalities are not subtenants in

Serbia, nor are we its co-tenants.

Either relationship would be

disastrous for the unity of the

Republic. It probably only seems to

me that the advocacy for a unified

SR Serbia and the autonomy of its

provinces established by the

Constitution – causes more fear

among some people than the slogan

`Kosovo Republic`.”42

It seems that from

1986 onwards, Stambolić's rhetoric

concerning Kosovo was partially

softened. Instead of resolute

demands and frustration over the

situation, there was also mention of

the positive examples of cooperation

between the republics and provinces

in his speeches. At that time and

later on, Stambolić explained this

“progress” in the relations by a

favourable climate that was created

after the political generational

change in Kosovo.43 Stambolić was

evidently pleased with Kosovo's

party leaders rallied around Azem

Vllasi and Kaqusha Jashari since May

1986. He emphasized that these cadre

changes were the result of the

correct politics towards Kosovo

which was conducted by the

republican authorities over the past

five years. In his subsequent

memoir, Stambolić gave numerous

examples of a thaw in the mutual

relations, cooperation and

reciprocity: from common legislation

to economic and political

cooperation. He especially pointed

to the statutory consolidation of

the LC organization in the entire

territory of the Republic in that

period.44

Regardless of the

political generational change in

Kosovo and positive changes in

mutual communication, Stambolić

continued to work with undiminished

ardour on constitutional changes

involving the reduction of

provincial powers through the

negotiations with other republics.

As for the key issues of the

Republic's constitutional

consolidation, Stambolić's efforts

can be followed until the end of his

active political involvement. Less

than ten days before the Eighth

Session of the Central Committee of

the LCS, he presented his exposé to

all councils of the Serbian Assembly

in which he explained the proposed

changes to the Constitution of SR

Serbia. He previously obtained the

consent of the leaders of other

republics and both provinces.45

As for the

recentralist demands at the federal

level, Stambolić considerably

expanded the programme advocated by

Draža Marković. It became more

complex, more concrete and more

comprehensive. In an ideological

sense, his concepts contained a lot

of reference to the workers'

self-management principles, so that

the proposed changes at the federal

level remained within the prevalent

value system. In the mentioned May

1981 speech, he used the truism

“togetherness and unity based on

self-management” instead of

insisting on state unity. Stambolić

pitted the model of “self-managing

economies”, based both on the

autonomy and togetherness

principles, against the concept of

“national economies” under which he

understood the economies at the

republican and provincial levels.46

In his interview

to the Zagreb daily Vjesnik in

September 1981, in the same context

of criticizing the self-sufficiency

of the republican and provincial

economies, Stambolić warned that the

“pluralism of self-managing

interests” would turn into the

“pluralism of nationalized

interests”.47 Thus, Stambolić tried to

legitimize the Serbian recentralist

positions which, in other republics,

were understood as leaning towards

etatism. Moreover, he accused others

of the sin of etatism – at both the

republican and provincial levels.

His affirmation of self-management

ideology in overcoming particular

etatisms found its unexpected

expression in his advocacy for the

“state of self-managing delegate

assemblies”. Namely, in the report

submitted at the session of the

Central Committee of the LCS in

September 1984, Stambolić called on

the municipalities to stand against

being “closed within organizations

of associated labour, the republics

and provinces within their

municipalities and regions, and the

federation within the republics and

provinces”. Stambolić also made a

distinction between the notions of

etatism and state, so that his

ideal-type state was a “state based

on self-management and a delegate

system in the form of federation,

including republics, provinces and

municipalities”.48

In his report

submitted to the Belgrade City

Committee of the League of

Communists in October 1983,

Stambolić critically perceived the

effects of the “absence of

self-managing unification”. Namely,

he held that, apart from

self-managing decentralization and

emancipation, “true deetatization”

also implied the process of

unification and cerntralization “no

matter how paradoxical it sounds”.

According to Stambolić, if there was

no this second unifying component,

the system would rush into the

danger of “decentralized etatism”.49

This was one more effort to present

the Serbian leaders' recentralist

tendencies as something being

consistent with the core ideological

premises on which Yugoslav socialism

was based.

In his criticism

of the use of the consensus

principle in decision making,

Stambolić went considerably further

than Draža Marković. Whereas

Marković's crtiticism only referred

to the decision-making process in

the Federation, Stambolić pointed

out that decision-making problems

also existed at the work

organization level. In fact,

decision making was only efficient

in the republics and provinces. In

that context, at the Eighteenth

Session of the Central Committee of

the LCS, held in November 1984,

Stambolić stated that “there can be

no more self-management in the

Federation than in the republics and

provinces”.50 He found the explanation

for these anomalies in the uneven

and inadequate development of the

self-management principles at

different societal and state levels.

Here is Stambolić's reasoning at the

Counselling Session of the LCS CC,

held on 22 October 1984:

“How

does our decision-making system work

today, from the basic organization

to the Federation? Excluding the

republican and provincial levels

where decisions on the most

important issues are made very

simply, very easily, quickly and,

sometimes, even rashly, so that they

are resolutely implemented without

any greater difficulty, in our

society – from the basic cell to the

Federation – a decision is made with

great difficulty and slowly. Haven't

we blocked associated labour, its

ability to decide and conduct a

policy? Haven't we also blocked the

decision-making ability at the

federal level? Hasn't this slowdown

in the development of

self-management led to a wrong

reproduction of the republic and the

province, thus aggravating the

functioning of the Federation?”51

As for the

“harmonization” principle, Stambolić

pointed to the adverse effects of

its implementation in almost all

fields of decision-making in the

Federation. According to Stambolić,

the consensus principle spread from

being used in determining and

managing the general development

aims where it was justified and

necessary, to being used in the

field of implementation and even

implementation control. He also said

that the federal councils turned

into “inter-republic committees”,

while the development of “republican

and provincial sciences” being in

service of upholding the political

views of their communities, also

made progress.52

The Counselling

Session, where Stambolić presented

these views, was also convened in

order to discuss the polemical tone

of the debate at the Fourteenth

Session of the Central Committee of

the LCY, which was held the previous

week. In the preceding part of this

article, we pointed to the

differences between the views of

Draža Marković and the Slovenian

members of the Central Committee.

Stambolić also emphasized and gave

unconditional support to Marković.

Moreover, he arbitrarily promoted a

great number of Marković's views as

the position taken by the Central

Committee of the LCY. It is evident

that the Serbian leaders were

unanimous in their criticism of the

principle of consensus decision

making in federal bodies. It also

seems that their stance against the

excessive use of consensus was also

supported by other republics. In the

letter sent by the Presidency of the

SFRY to the Federal Assembly on 13

November 1984 regarding the

determination of the country's

socio-economic development in 1985,

there was also a recommendation in

line with Marković’s and Stambolić’s

reasoning.53

As it seems, this

fact shows that the Serbian cadres

had a broader Yugoslav concept

within which they expected to win

support for their views and changes

in the economic relations in the

country. Namely, as the inflationary

tendencies in Yugoslavia were

gaining momentum, the gap between

the less developed republics and the

developed ones, primarily Slovenia,

was deepening. In his memoir, Raif

Dizdarević described with some

bitterness the negotiations with the

Slovenians about the structure of

development policy in Bosnia and

Herzegovina, which they wanted to

condition. Dizdarević also

criticized the Slovenian policy of

“preserving the acquired positions

and privileged status in the

economy“. Namely, the inflationary

tendencies inflicted damage to the

republics in which the “power

industry, basic industry and

production of raw materials,

intermediates and food were

dominant“, since the prices of their

products were set by the federal

government. Such was the economic

structure not only in Bosnia and

Herzegovina, but also in Serbia and

other less developed republics.54 As it seems, this

fact shows that the Serbian cadres

had a broader Yugoslav concept

within which they expected to win

support for their views and changes

in the economic relations in the

country. Namely, as the inflationary

tendencies in Yugoslavia were

gaining momentum, the gap between

the less developed republics and the

developed ones, primarily Slovenia,

was deepening. In his memoir, Raif

Dizdarević described with some

bitterness the negotiations with the

Slovenians about the structure of

development policy in Bosnia and

Herzegovina, which they wanted to

condition. Dizdarević also

criticized the Slovenian policy of

“preserving the acquired positions

and privileged status in the

economy“. Namely, the inflationary

tendencies inflicted damage to the

republics in which the “power

industry, basic industry and

production of raw materials,

intermediates and food were

dominant“, since the prices of their

products were set by the federal

government. Such was the economic

structure not only in Bosnia and

Herzegovina, but also in Serbia and

other less developed republics.54

On the other hand,

the Slovenian economy mostly

produced finished products for the

market, so that it earned profit

under inflationary conditions.

Namely, the retail prices of these

products were not

government-controlled, which the

representatives of other republics

considered as a specific kind of

monopoly and underserved privilege.

Dizdarević says that the Bosnian

side used this argumment against

Slovenia's criticism of its economic

policy. The only way to change such

economic relations was to resort to

government intervention, However,

the typical Slovenian response to

the leaders of Bosnia and

Herzegovina was to label them as the

proponents of etatism. Namely,

France Popit argued with a dose of

arrogance that agreeing to etatism

was something which, as a rule, was

resorted to by underdeveloped ones,

since “he who lives a hard life is

always ready to support the etatist

measures that will improve it”.55

The proposed

positions for the mentioned

Fourteenth Session of the Central

Committee of the LCY in 1984

involved the criticism of the

preservation of monopoly. Namely, it

was necessary “to stand resolutely

against those defending their

undeservedly acquired positions,

that is, their monopoly and

privileged status”. We learn about

this from the speech of Andrej

Marinc, the Slovenian member of the

Central Committee of the LCY, who

dismissed these demands if “such a

formulation refers to the more

developed republics and autonomous

provinces or exporting organizations

of associated labour”.56 As for the

abolition of a monopoly status in

price formation, in his keynote

address at the Seventeenth Session

of the Central Committee of the LCS

on 28 September 1984, Ivan Stambolić

spoke about the need for the “faster

removal of sectoral and territorial

price disparities” at the federal

level.57 The Serbian leaders probably

expected to win support for their

projects from the less developed

republics should the consensus

principle be eliminated from

collective decision making at the

Yugoslav level. Namely, the economic

advantages of so-called monopoly and

privileges were enjoyed only by

Slovenia and probably, to a degree,

Croatia. This means that the Serbian

efforts to change the status quo

within the Yugoslav framework could

win support. However, before

Slobodan Milošević came to power in

Serbia such outvoting was not an

item on the agenda of the Serbian

leaders.

There is one more

element of Stambolić's centralism

that is somewhat illogical and needs

attention. Namely, he often insisted

on the unhindered movement of goods

and services within the entire

Yugoslav space. Consequently,

Stambolić pleaded for a unified

Yugoslav market, although he

represented the interests of the

republic whose level of economic

development was slightly below the

Yugoslav average. One would expect

that such a doctrine was advocated

by the economically more developed

republics that could take full

advantage of free trade. It seems

that in this case, whether

consciously or not, Stambolić gave

priority to political reasoning

rather than to economic logic. After

all, his arguments about this

specific self-managing economic

liberalism were more ideological and

political than economic:

“[...] the tendencies towards

squeezing out the market almost

always strengthen etatism, while the

suppression of the unity of the

Yugoslav market led in many ways to

the strengthening of decentralized

etatism, which can easily become the

basis of nationalism. When we wrote

down in the Constitution that

economic relations should be

regulated by self-management

agreements and compacts, we were

guided by the revolutionary aim to

increasingly harmonize different

interests on a self-management

basis. [...] Instead of resolving

the conflicts of material interests

on a unified Yugoslav market, which

is the locus of such conflicts, they

are again transmitted to political

relations between the republics and

provinces, where they do not belong

and often turn into interethnic,

that is, republican and provincial

misunderstandings and clashes.”58

Consequently, the

recentralists advocated the idea of

“togetherness” at all costs and

under all circumstances. As an

ardent proponent of the

strengthening of federal powers and

state unity within SR Serbia,

Stambolić enjoyed almost the same

reputation as Draža Marković in the

Yugoslav circles. Namely, he was

also aware that in other republics

he was considered a nationalist. At

the time of the Eighth Session,

Stambolić had no significant support

from other parts of Yugoslavia.59

Dragiša Buca Pavlović

It seems that the

political messages and warnings of

Dragiša Buca Pavlović (1943-1996),

the forgotten veteran of the fight

against nationalism and tragic hero

of the Eighth Session, have not lost

their topicality to this day. In his

public appearances in September

1987, Pavlović was the first to

point to the structural problems and

disastrous impact that Milošević's

inflammatory political rhetoric,

irresponsible print media and

“patriotic” intellectual elite would

have on overall social relations.

Dragiša Buca Pavlović held the

position of President of the

Belgrade City Committee of the LCS

for a relatively short time or, more

exactly, from May 1986 until the 8th

Session. The general public mostly

does not know that Pavlović’s

removal from this position was the

key item on the agenda of the Eighth

Session. The speech delivered by

Buca Pavlović on that occasion was

probably the last defence of the

most significant achievements and

values of Yugoslav socialism on the

Serbian political scene. It seems that the

political messages and warnings of

Dragiša Buca Pavlović (1943-1996),

the forgotten veteran of the fight

against nationalism and tragic hero

of the Eighth Session, have not lost

their topicality to this day. In his

public appearances in September

1987, Pavlović was the first to

point to the structural problems and

disastrous impact that Milošević's

inflammatory political rhetoric,

irresponsible print media and

“patriotic” intellectual elite would

have on overall social relations.

Dragiša Buca Pavlović held the

position of President of the

Belgrade City Committee of the LCS

for a relatively short time or, more

exactly, from May 1986 until the 8th

Session. The general public mostly

does not know that Pavlović’s

removal from this position was the

key item on the agenda of the Eighth

Session. The speech delivered by

Buca Pavlović on that occasion was

probably the last defence of the

most significant achievements and

values of Yugoslav socialism on the

Serbian political scene.

Pavlović was the

first to recognize the phenomenon

now recognized as the tabloidization

of print media in growing hysteria

and irresponsible and flammable

texts published in Politika and

Politika ekspres, beginning with the

event at Kosovo Polje in 1987 and,

in particular, the massacre in the

military barracks in Aleksinac in

September of the same year. The new

trends in the editorial policies of

the Politika publications followed

the changes in public rhetoric,

whose main protagonist was Slobodan

Milošević. During the period od

socialism, the principles including

inter-ethnic respect and extreme

caution in broaching the theme such

as inter-ethnic relations were

patiently cherished. These

principles, respect and the rules of

the proclaimed policy of brotherhood

and unity were also reflected in

journalism. It is surprising how the

whole system could turn into its

opposite within just a few months in

1987. Milošević’s first open critic

was also the first kadrovik to be

ousted by Milošević on his road to

power. The removal of Pavlović and,

later, Stambolić from the Serbian

political scene meant the removal of

the last sincere supporters of

leftist ideas whch, as a political

option, did not (and does not) exist

in (post)transition Serbia.

On the basis of

the foregoing, Pavlović should have

been the political opposite of

Slobodan Milošević in every respect.

However, for the purposes of this

study and in the context of the

defined terminological designations,

Pavlović will be considered as part

of the recentralist school of

thought to which Milošević also

belonged. During the short period of

his involvement in so-called high

politics, At party forums, Pavlović

also expressed his views on the

autonomy of the provinces and

functioning of the federation. With

respect to these issues, he followed

Ivan Sambolić's political course

which, as interpreted by Pavlović,

was formulated in a more abstract

and more academic way. It is evident

at first glance that, when speaking

about these issues, Pavlović

referred even more to the

ideological postulates of workers'

self-management.

In dealing with

the problems of the non-functioning

of a unified Yugoslav market and

“autarkicity” of the Yugoslav

economies, Pavlović held that it was

the question of an unconstitutional

takeover of the “supreme

arbitration” powers by the republics

and provinces. According to

Pavlović, the “supreme arbitration”

right only belongs to “associated

workers” who promote their relations

within the system of a “pluralism of

self-managing interests”. Pavlović

labelled everything else as etatism

at the national, regional,

municipal, republican or provincial

level, or the level of organization

of associated labour. He held that

the closing off of the autarkic

circles of the economy was not only

as an anomaly of the system, but

also something that posed a threat

to the overall development of

socialism in the country:

The

pooling of labour is something quite

different than the

“republicanization-provincialization”

or “ourization“ of the economy. Will

we slow down or speed up our

progress toward socialism and

communism if the economies of the

republics, provinces and regions

continue to develop as more or less

autarkic economic structures? Does

“autarkization” lead us to socialism

or somewhere else – probably

backwards?60

In dealing with

the economic emancipation trends in

the federal units and absence of

direct investments from the more

developed republics to the less

developed ones, Pavlović criticized

these phenomena proceeding from the

basic positions of Marxism. Namely,

the tendencies towards closing the

eonomies were explained as the

efforts of “people to appropriate

surplus labour for themselves”.61

Although it was not explicitly said,

this line of reasoning equated the

egoism of the provincial and

republican nomenclatures with the

behaviour expected under conditions

of classical capitalism. Bearing in

mind the dominant ideology of

workers' self-management, this was

probably the sharpest possible

criticism of the ideological

opponents. In dealing with

the economic emancipation trends in

the federal units and absence of

direct investments from the more

developed republics to the less

developed ones, Pavlović criticized

these phenomena proceeding from the

basic positions of Marxism. Namely,

the tendencies towards closing the

eonomies were explained as the

efforts of “people to appropriate

surplus labour for themselves”.61

Although it was not explicitly said,

this line of reasoning equated the

egoism of the provincial and

republican nomenclatures with the

behaviour expected under conditions

of classical capitalism. Bearing in

mind the dominant ideology of

workers' self-management, this was

probably the sharpest possible

criticism of the ideological

opponents.

As for the

autonomous provinces, Pavlović

elaborated, in essence, the concepts

developed by Draža Marković and Ivan

Stambolić. We also find the elements

of the constitutional and legal

arguments relating to the formation

of a unified economic and state

space within SR Serbia and

insistence on the equality of SR

Serbia with other republics within

the federation. He used the social

development plan of SR Serbia as an

example and insisted that this

document should refer to the entire

Serbian territory. Namely, the

relevant legal regulations

stipulated that social development

plans should be adopted by

“socio-political communities”, while

the territory of Serbia proper was

never and nowhere defined as such a

community. Pavlović said that the

development plan of SR Serbia was

not adopted for a decade due to

formal legal reasons and opposition

to it in the provinces, this

pointing to the significant degree

of disempowerment of this republic

compared to other Yugoslav

republics.62

Much of Pavlović's

argumentation relating to the

settlement of the Kosovo problem

referred to cooperation with Kosovo

institutions.63 This is not surprising

in view of the fact that the short

period of his involvement in

politics coincided with the

mentioned generational change in the

Kosovo leadership and change in

Stambolić's rhetoric on the Kosovo

problem. As for political, cultural

and economic cooperation with

Kosovo, Pavlović's views mostly

corresponded to those of Ivan

Stambolić during the period

1986-1987. Pavlović also spoke

exhaustively about cooperation with

Kosovo at the Eighth Session when

such rhetoric was already considered

“obsolete” by the nationalist group

rallied around Slobodan Milošević.64

Slobodan Milošević

Milošević belonged

to the narrow circle of Serbian

leaders since late 1983. However, he

did not display any special interest

in the so-called Kosovo problem

until his visit to Kosovo Polje in

April 1987. In the collection of his

public speeches, the Kosovo problem

was mentioned for the first time at

the conference of the Presidents of

the Regional Committees of the LCY

in June 1986. Milošević also spoke

about Kosovo at his meeting with the

political activist group from

Kragujevac in December 1986.

Although Stambolić already softened

his rhetoric on Kosovo to a

significant extent, Milošević still

used the “old” vocabulary to

designate the events in Kosovo

immediately after the rebellion in

1981. Whereas Stambolić pointed to

the possible ways of cooperation

with the new provincial leadership,

Milošević simply labelled these

events as a “counterrevolution” and

the settlement of the problem as the

“elimination of the consequences of

a counterrevolution”.65 Apart from

casually mentioning the situation in

Kosovo on these two occasions, where

one can recognize the embryo of

Milošević's harsh rhetoric in the

future, it seems that at the

beginning of his political career he

was not much concerned about the

problems of Serbia's southern

autonomous province. Milošević belonged

to the narrow circle of Serbian

leaders since late 1983. However, he

did not display any special interest

in the so-called Kosovo problem

until his visit to Kosovo Polje in

April 1987. In the collection of his

public speeches, the Kosovo problem

was mentioned for the first time at

the conference of the Presidents of

the Regional Committees of the LCY

in June 1986. Milošević also spoke

about Kosovo at his meeting with the

political activist group from

Kragujevac in December 1986.

Although Stambolić already softened

his rhetoric on Kosovo to a

significant extent, Milošević still

used the “old” vocabulary to

designate the events in Kosovo

immediately after the rebellion in

1981. Whereas Stambolić pointed to

the possible ways of cooperation

with the new provincial leadership,

Milošević simply labelled these

events as a “counterrevolution” and

the settlement of the problem as the

“elimination of the consequences of

a counterrevolution”.65 Apart from

casually mentioning the situation in

Kosovo on these two occasions, where

one can recognize the embryo of

Milošević's harsh rhetoric in the

future, it seems that at the

beginning of his political career he

was not much concerned about the

problems of Serbia's southern

autonomous province.

Ivan Stambolić

also spoke of Milošević's lack of

interest in Kosovo. According to

him, Milošević allegedly tried to

convince him to let the provinces

alone and turn attention to the

settlement of the Yugoslav problems.66

Today, it may sound paradoxical that

his later opponents Draža Marković,

Ivan Stambolić and Buca Pavlović –

the politicians removed from

politics by Milošević due to their

alleged opposition to the settlement

of the Kosovo problem – were much

more concerned about the problem of

the provinces. In that initial

period, Milošević's recentralism was

reflected in his advocacy of a

unified Yugoslav market and more

efficient performance of federal

bodies. Milošević was especially

concerned about the market

integration problem, which he

tackled in almost every public

speech. These arguments, in their

fully developed form, are found in

Milošević's and Stambolić's speeches

at the Seventeenth Session of the

Central Committee of the LCS, so

that it is difficult to establish

its authorship.67 In any case, in the

subsequent period Milošević insisted

much more on this, largely

ideological concept of self-managed

integration than Stambolić.

In further text, I

will analyze some characteristic

points made by Milošević in his

rhetorical advocacy of the

self-managed integration of the

Yugoslav market. At the mentioned

session, which was held er 1984, he

designated the obstacles to the

functioning of a unified market as

the “essential political question

posing a threat to the survival of

the system”. Milošević declared all

obstacles unconstitutional because

they violated Article 254 of the

Constitution of the SFRY,

sanctioning the placing of economic

agents in an unequal position for

any reason. At the Eighteenth

Session of the Central Committee of

the LCS, which was held in November

1984, he devoted his attention

almost entirely to the problems

arising from the non-integrated

system of self-managing

organizations (BOALs, work

organizations, self-managing

communities of interest, provinces,

republics, municipalities, etc.),

whose “administrations defend the

rights of `their` working class from

each other”. Milošević insisted that

he was speaking in the name of the

working class and its interests:

“Workers are massively aware of

that. The worker does not accept

that he must change the bus at the

border between two republics, or

even two municipalities, when he

does not have to do that when

travelling abroad. The peasant does

not accept that the police wait for

him at the republican-provincial

border in order to search his

baggage. Our man does not agree with

the situation that two trains

carrying the same goods pass each

other on adjacent tracks; one train

carries exports, while the other

carries more expensive imports.”68

The last sentence

shows that his insistence on a

unified market also implied export

restrictions. This topic was also

broached by Ivan Stambolić in his

interview with the newspaper

Komunist in August 1985. He said,

for example, that wheat from

Vojvodina was exported, while at the

same time Kosovo and Serbia proper

had to import it at a higher price.

Trepča exported its ore, while the

Copper Rolling Mill in Sevojno and

Cable Factory in Svetozarevo did not

have it for their needs.69 These

products and intermediates should be

preserved for economic agents in the

country, that is, Serbia proper.

Consequently, Milošević and

Stambolić pleaded for a variation of

Fichte's “closed commercial state“,

which could be considered their

principled commitment if there was

no constant reference to the

building of an export-oriented

economy. If there economic efforts

were successful, the greatest

benefit would be derived by the

economically more developed

republics, primarily Slovenia. The

Serbian recentralists' imperatives