|

Case

study 3

INTRODUCTION

International

criminal trials do allow individuals

to be held accountable for what may

have been state violence committed

through institutional state

structures and state bureaucracies;

but a focus on individual criminal

responsibility in the investigation

into and prosecution of alleged mass

atrocities has a number of potential

pitfalls. The first is that charging

a single person with extensive

crimes spread over years carries the

risk of ‘over-prosecution’ or even

of distorting the complex historical

and political processes that led to

the mass atrocities in question. The

second pitfall is that isolating a

single political leader as

responsibility for mass atrocities

risks scapegoating an individual for

what was in fact can also be seen as

the criminality of a state and of

state institutions.

Yet, there is no

doubt that Slobodan Milošević, due

to his de jure and de facto powers,

and his role as the leader of all

Serbs by 1990 bears a huge, if not a

crucial responsibility of the

violent disintegration of the SFRY.

The opinion of some historians is

that existing interpretations of the

disintegration of Yugoslavia are

based chiefly on “contradictory and

hardly impartial evidence” such as

witness accounts, personal memoirs,

and Milošević’s own public

statements. This view is sometimes

supported by the assertion that

Milošević was “extremely secretive,

leaving very little documentary

trace,” and that his strategic

decisions were made in the seclusion

of his home, where only his wife and

a small group of advisors were party

to his thoughts.1 The ICTY

investigation into Milošević’s

political and criminal behaviour had

initially found that Milošević

preferred one-on-one meetings and

had suggested that these meetings,

both domestic and international,

were not officially recorded and

archived as prescribed by domestic

laws and regulations. Milošević was

said to have been regularly

accompanied by Goran Milinović, his

Chef de Cabinet, who supposedly made

notes.2 But in 2001, the Prosecution

discovered that there were indeed

records of these meetings; and that

the most interesting – and arguably

most valuable – material was located

in the state archives of the FRY and

Serbia.

THE SLOBODAN MILOŠEVIĆ TRIAL ARCHIVE

Although, there is

some recognition among historians of

the need to explore new material

that has emerged from the ICTY and

government archives, there have been

a few attempts to incorporate that

material in the studies in the

history of the SFRY and its demise.

And, for good reason, because

research of the trial record reveals

a different picture – that Milošević

did at times leave traces, and that

audio and video records in some

cases irrefutably establish the

veracity of certain events or

claims.

Documents tendered

by the Prosecution and pertaining to

Milošević’s state of mind before,

during, and after the wars in

Croatia, BiH, and Kosovo – which

were analysed for this research –

are thus important to the developing

historiography of the conflict.

During the early years of war, in

the period relevant to the Croatia

indictment, telephone intercepts,

records of meetings of the

Presidency of the SFRY (PSFRY), and

a video known as the Kula Camp Video

illustrate the evolution of

Milošević’s state of mind. For the

period covered by the Bosnia

indictment, this evidence again

includes telephone intercepts, but

also records from two FRY state

organs, the Council for

Harmonization of Positions on State

Policy and the Supreme Defence

Council (SDC). For years covered by

the Kosovo indictment, documents

from an ad hoc body known as the

Joint Command were of great value,

but the key piece of evidence shown

at the trial was undoubtedly a video

that featured a Serbian-based

paramilitary group, the Scorpions,

executing civilians taken from

Srebrenica in the summer of 1995.

The Scorpions were re-deployed by

the Serbian Ministry of Internal

Affairs (Ministarstvo Unutrašnjih

Poslova, or MUP) in 1999, when they

again committed crimes against

civilians. Although footage from the

Scorpions Video was shown during the

cross-examination of a Defence

witness, the video was never

tendered into evidence. Yet, what

transpired in the courtroom was the

cause of an unprecedented uproar in

the world and in the region. Documents tendered

by the Prosecution and pertaining to

Milošević’s state of mind before,

during, and after the wars in

Croatia, BiH, and Kosovo – which

were analysed for this research –

are thus important to the developing

historiography of the conflict.

During the early years of war, in

the period relevant to the Croatia

indictment, telephone intercepts,

records of meetings of the

Presidency of the SFRY (PSFRY), and

a video known as the Kula Camp Video

illustrate the evolution of

Milošević’s state of mind. For the

period covered by the Bosnia

indictment, this evidence again

includes telephone intercepts, but

also records from two FRY state

organs, the Council for

Harmonization of Positions on State

Policy and the Supreme Defence

Council (SDC). For years covered by

the Kosovo indictment, documents

from an ad hoc body known as the

Joint Command were of great value,

but the key piece of evidence shown

at the trial was undoubtedly a video

that featured a Serbian-based

paramilitary group, the Scorpions,

executing civilians taken from

Srebrenica in the summer of 1995.

The Scorpions were re-deployed by

the Serbian Ministry of Internal

Affairs (Ministarstvo Unutrašnjih

Poslova, or MUP) in 1999, when they

again committed crimes against

civilians. Although footage from the

Scorpions Video was shown during the

cross-examination of a Defence

witness, the video was never

tendered into evidence. Yet, what

transpired in the courtroom was the

cause of an unprecedented uproar in

the world and in the region.

Materials selected

as evidence by the Prosecution and

Defence in the Milošević case

constitute an unmatched historical

source; and even with some gaps in

the trial record, it incorporates

documents from state archives that

would have otherwise been

unavailable to the public and to

researchers for many decades.

Indeed, some of the trial material

would never have surfaced at all

were it not for the obligation of

states to cooperate with the ICTY,

or more precisely, to provide the

OTP and the Defence with materials

upon request. Still, there remains

trial material that is officially

available and yet inaccessible to

the public; and the

(in)accessibility of ICTY records to

the public is an important issue.

The ICTY Court Record (ICR), an

electronically accessible database,

is sometimes more of a challenge

than an aid to researchers because

it comprises only a selection of

materials, not the full record of

every trial, and remains incomplete

for a number of technical and other

reasons.3

What makes the

Milošević trial record especially

interesting as a source of history

is the fact that it includes

responses by Milošević himself to

every piece of evidence brought

against him. Milošević not only

represented himself in court, and

therefore responded in that capacity

to the evidence presented, but also

made remarks throughout the trial

from the standpoint of a man

attempting to defend his political

and private decisions.

The test for the

introduction of evidence in court is

bound by a strict forensic process,

which consists of presentation of

evidence by one trial party,

followed by cross-examination by the

opposing party, and eventually the

right of re-direct by the first

party. The product of this process –

forensic truth – is different from

historical truth in several ways.

For one, a historian is not bound by

the same forensic process in order

to include a source in a historical

account and instead seeks

corroboration in other available

sources, of a greater variety than

are admissible in a courtroom, and

through this analysis develops a

historical interpretation of an

event. And, over the course of time,

this interpretation might be altered

by other historians, which is

another way in which historical and

legal narratives about the same

topic may differ considerably; as

the latter is captured in closing

arguments and judgements, which are

formed in the normative legal

framework and in rigid court

procedures, and remain fixed in

time.

At the ICTY, a

discrepancy between the public

perception of responsibility for

mass atrocities and the legal

requirements for proof of the crimes

alleged against an individual such

as Milošević have often led to the

accrual of a great deal of evidence

in order to prove ‘the obvious’ in a

court bound by strict legal rules

and procedures.4 For every general

allegation against Milošević,

probative evidence was needed to

establish that the crime actually

happened and that Milošević was

criminally responsible for it. The

large amount of evidence presented

by the parties during the trial was

also partially due to the changing

world in which we live. Modern

technology made the wars in the

former Yugoslavia into media

spectacles, watched daily on the

television and captured on the

Internet. Minute details of the

conflicts became available and

accessible to the public in nearly

all the world’s languages; and

material from these ‘open sources,’

potentially relevant as evidence,

was almost unlimited.5

Notwithstanding

the huge amount of audio, video, and

written material that exists about

the conflicts and about the role of

Slobodan Milošević in them, ICTY

Prosecutors – unlike their Nuremberg

counterparts – did not have full or

easy access to documentary material

from the archives of the former

leader’s country.6 Documents from the

official archives of the FRY and the

Republic of Serbia, considered more

important from a forensic point of

view than open source materials,

were difficult and sometimes

impossible to obtain.7 This was in

stark contrast to the experience of

prosecutors in Nuremberg, for which

Allied Powers had simply seized the

state and Nazi Party archives of

defeated Germany for use as evidence

in court. Nonetheless, evidence that

did come directly to the ICTY from

state archives in Serbia, the FRY,

the RS, and the RSK makes the

Milošević trial record particularly

valuable, as it includes state

documents that would otherwise have

remained protected for decades or

even longer. Once used in court as

evidence, most of these documents

became public.

The Milošević

trial record comprises transcripts,

material tendered as evidence,

motions on administrative and

procedural matters, and decisions

and judgements of the Trial Chamber

and Appeals Chamber. The record –

the main source for this research –

is so large that it is too

substantial to be analysed in a

single academic study, and it is not

examined in full here. Still,

missing source materials that were

requested but never produced

represent a gap; meaning that the

trial record, while vast, is not

exhaustive. And so, despite its

size, the trial record alone was

insufficient for the task of this

research, and sources from outside

the trial proceedings – known as

extratrial material – were also

analysed.

Extratrial

material originating from the ICTY

and OTP includes investigative and

analytical documentation, such as

reports by in-house investigators,

researchers, and analysts on the

Milošević trial team, which were not

used per se in court proceedings.

ICTY internal policy documents on

topics such as indictment strategies

or how to conduct the trial also

fall under the designation of

extratrial material. In other words,

a considerable amount of extratrial

material was used for the court’s

investigative and research purposes

without becoming a part of the

official trial record. The ICTY

database contains diverse materials

collected by the OTP, from

demographic data on the former

Yugoslavia to media reports that may

have been used in preparation for

cross-examination of Defence

witnesses to seemingly endless

supporting evidence and courtroom

exhibits.8 Access to some of these

materials remains limited to OTP

employees until, or unless, they are

made publicly available, which will

depend on the conclusions of the

Mechanism for International Criminal

Tribunals (MICT).

SCHOLARLY DEBATE ON THE CAUSES AND

CONSEQUENCES OF

THE DISINTEGRATION OF YUGOSLAVIA

The narrative that

developed over the course of the

trial tracked Milošević’s political

motivations, objectives, and

intentions and the trial record

provides a unique chance for

historians to revisit existing

disputes and controversies about

historical details, the legality of

particular political decisions and

actions, and the real nature of

policies implemented by leaders at

both the republic and federal

levels. Many politicians who were in

power at the outbreak of violence in

fact testified as Prosecution or

Defence witnesses.9 Their testimonies

were further enriched by Milošević’s

courtroom performance – his

comments, protestation, denials, and

even his body language regularly

gave away more than he would have

revealed had he not represented

himself.10 The narrative that

developed over the course of the

trial tracked Milošević’s political

motivations, objectives, and

intentions and the trial record

provides a unique chance for

historians to revisit existing

disputes and controversies about

historical details, the legality of

particular political decisions and

actions, and the real nature of

policies implemented by leaders at

both the republic and federal

levels. Many politicians who were in

power at the outbreak of violence in

fact testified as Prosecution or

Defence witnesses.9 Their testimonies

were further enriched by Milošević’s

courtroom performance – his

comments, protestation, denials, and

even his body language regularly

gave away more than he would have

revealed had he not represented

himself.10

The part Milošević

played in events of the 1980s and

1990s has also been explored in a

number of political biographies and

is an important sub-topic of

analysis. However, the most

well-known of these biographies,

written in both English and Serbian,

were published before his trial or

in the same year that it started.11

This means that few authors have

presented the trail of evidence that

was followed in the courtroom to

establish responsibility for the

break-up of Yugoslavia and, more

importantly, the violence that

followed.

Did Milošević

genuinely try to save Yugoslavia?

Did he, together with others,

inadvertently cause its

disintegration through a series of

well-intended blunders?12 Or, did he

actively work to re-draw its

borders?

A majority of

authors agree that Milošević played

a central role in events that

unfolded in the former SFRY between

1987 and 1999. For the purposes of

this study, three categories of

interpretations of Milošević’s role

in the disintegration of Yugoslavia

have been identified:

intentionalist, relativist, and

apologist.13 ‘Intentionalists’ see

Milošević as having dictated the

pace of the Yugoslav crisis through

well-articulated and planned

objectives that drove the other

republics away.14 According to this

view, violence was used cynically

and practically with a clear

purpose. The intentionalist

perspective is that violence against

non-Serbs was the result of a

pre-meditated strategy – the success

of which is irrelevant – to secure

Milošević’s promise of “All Serbs in

a Single State” at any cost.15

Alternative to

this are authors who tend to see

Milošević as an intelligent and

ruthless politician but not a good

tactician or strategist, whose

politics were mostly reactive.16 These

‘relativists’ see Milošević’s

policies as responses to

developments that were driven by

leaders of Slovenia, Croatia, BiH,

and Kosovo, and by the international

community. From this standpoint,

Milošević genuinely wanted to

preserve Yugoslavia but did not

succeed.17 Relativists perceive

Milošević as an immensely ambitious

politician who endeavoured to

achieve more than he was capable of;

and his rule has been cast by

authors in this camp as a sequence

of mistakes and failures – at the

national and international levels.18

The violence that accompanied the

disintegration of Yugoslavia is thus

explained as resulting from a

complicated interplay of many

factors, leading to an escalation of

the crisis that was beyond the

control of Milošević alone.

‘Apologists’ share

the opinion held by relativists

regarding the role of the republics

that sought independence and of the

international community in the

disintegration of Yugoslavia. Yet

they not only see his goal to

preserve Yugoslavia as

well-intentioned but also defend his

politics and decision-making in

general.19 They downplay Milošević’s

calculating and ruthless side to

recast him as a somewhat clumsy,

wayward, and inconsistent

authoritarian leader who merely

failed to deliver on promises he

made.20

In fact,

apologists frame Milošević as an

atypical authoritarian ruler who

could have secured his power by

force but was willing, instead, to

compromise his initial goals.21

Apologists also dismiss arguments

about the influence of Greater

Serbia ideology on Milošević or on

Serbia’s involvement in the ethnic

cleansing in Croatia, BiH, or

Kosovo. They stress that it was NATO

that committed grave crimes in

Serbia and Kosovo, for which nobody

has been held accountable. And, as

to Milošević’s domestic criminality,

some apologists say that there has

been no definitive proof of his

personal involvement in

assassinations that took place

during his rule; and some go further

in their absolution of him, arguing

that even if he did play a role in

these murders, there were “not many

such examples.”22 Apologists see

Milošević as having been a true

statesman who resisted foreign

pressure.23

TRIAL EVIDENCE AND HISTORICAL

NARRATIVE ON SERBIA’s ROLE IN

DISINTEGRATION OF the SFRY

For the purpose of

this study, the Slobodan Milošević’s

ICTY trial archive record will be

analysed in search for the material

about three events that are still a

matter of historical controversies

as it has still be contested if the

events ever took place or if they

did happen what is their historical

and political significance. As

illustration the historical

significance of the mass atrocities

trial archives, three events will be

examined by using the material

available in the ICTY trial record

of the Slobodan Milošević’s

unfinished trial: (1) Greater Serbia

as Serbian State Ideology in the

1990s (2) the SANU Memorandum – an

ideological blueprint for Serbia’s

politics under Slobodan Milošević?

(3) the Karađorđevo meeting of March

1991and the premeditated plans to

partition Bonsia and Herzegovina

GREATER SERBIA AS SERBIAN STATE

IDEOLOGY in the 1990s

Questions about

Milošević’s role in the collapse of

the SFRY are most relevant where

they concern how it became violent.

When, why, and by whom was violence

unleashed? And for what purpose? In

scholarly literature, the outbreak

of violence has often been ascribed

to Greater Serbia ideology and

efforts to create a Serb state. Some

authors hold that Milošević’s plans

corresponded with the historical

goals of Greater Serbia ideologues

but that his political choices

actually had no basis “in any

particular scheme.”24 Criminal

investigations into the language of

leaders attempt to uncover

derogatory and racist words that

might represent prejudice or hatred

toward members of a targeted enemy

group. This evidence is essential to

revealing the state of mind of an

accused, needed to establish

criminality. To prove a criminal

case, both the words and deeds of an

accused are equally important.

Although actus reus – the criminal

act itself, such as killing or rape

– is an essential starting point for

every criminal investigation,

proving the criminality of a

political leader focuses more on

mens rea, the criminal mind, which

must be shown to have led to or

accompanied the actus reus.

Throughout the Milošević trial,

witnesses who were once close to or

engaged in political negotiations

with him testified that there was

often a discrepancy between

Milošević’s words and deeds. So,

what were Milošević’s true

intentions and why did he try to

obscure his political goals? Was it

because he knew that the creation of

a single state for all Serbs could

be achieved only through violence

against non-Serbs? Questions about

Milošević’s role in the collapse of

the SFRY are most relevant where

they concern how it became violent.

When, why, and by whom was violence

unleashed? And for what purpose? In

scholarly literature, the outbreak

of violence has often been ascribed

to Greater Serbia ideology and

efforts to create a Serb state. Some

authors hold that Milošević’s plans

corresponded with the historical

goals of Greater Serbia ideologues

but that his political choices

actually had no basis “in any

particular scheme.”24 Criminal

investigations into the language of

leaders attempt to uncover

derogatory and racist words that

might represent prejudice or hatred

toward members of a targeted enemy

group. This evidence is essential to

revealing the state of mind of an

accused, needed to establish

criminality. To prove a criminal

case, both the words and deeds of an

accused are equally important.

Although actus reus – the criminal

act itself, such as killing or rape

– is an essential starting point for

every criminal investigation,

proving the criminality of a

political leader focuses more on

mens rea, the criminal mind, which

must be shown to have led to or

accompanied the actus reus.

Throughout the Milošević trial,

witnesses who were once close to or

engaged in political negotiations

with him testified that there was

often a discrepancy between

Milošević’s words and deeds. So,

what were Milošević’s true

intentions and why did he try to

obscure his political goals? Was it

because he knew that the creation of

a single state for all Serbs could

be achieved only through violence

against non-Serbs?

Since 19th

century, Greater Serbia ideology is

associated with territorial

expansionism, advocating that the

Serbian state be enlarged to the

south (into Macedonia and Kosovo)

and to the west (into BiH and

Croatia). Early proponents of a

Greater Serbia aspired to expand

Serbian borders into Ottoman and

then Habsburg territories – which

had ethnically mixed populations

with large numbers of non-Serbs –

and the Prosecution argued that this

history of efforts to enlarge

Serbian territory was one of mass

atrocities against those non-Serb

populations. In establishing

Milošević’s criminal state of mind,

it was essential for the Prosecution

to present evidence on his adoption

of this ideology that has long

inspired attempts by Serbian

political elites to create an

ethnically-defined Serbian state;

efforts known to frequently have

been accompanied by violence.25

Greater Serbia Ideology and a

History of Violence:

From Terrorism to Mass Atrocities

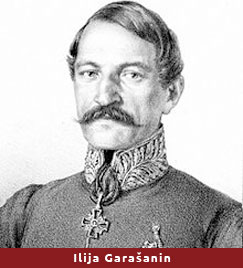

Expert witnesses

for both the Prosecution and Defence

addressed the history of the Greater

Serbia concept. Prosecution Expert

Witness on history Audrey Budding

credited the term to Serbian

politician Ilija Garašanin

(1812-1874), who wrote a short

nationalistic manifesto in 1844

known as Načertanije (The Outline),

which identified the borders of a

future Serbian state.26 The document

was kept secret until it was finally

published in 1906.27 Since Garašanin’s

time, there has been much debate

over his ideology and what the

notion of Greater Serbia implies. Is

it a unified South Slavic state

incorporating a large number of

non-Serbs, or a Serbian national

state meant to unite Serbs and

connect all predominantly Serb

territories? In other words, does it

reflect Yugoslavism or Serb

nationalism? Expert witnesses

for both the Prosecution and Defence

addressed the history of the Greater

Serbia concept. Prosecution Expert

Witness on history Audrey Budding

credited the term to Serbian

politician Ilija Garašanin

(1812-1874), who wrote a short

nationalistic manifesto in 1844

known as Načertanije (The Outline),

which identified the borders of a

future Serbian state.26 The document

was kept secret until it was finally

published in 1906.27 Since Garašanin’s

time, there has been much debate

over his ideology and what the

notion of Greater Serbia implies. Is

it a unified South Slavic state

incorporating a large number of

non-Serbs, or a Serbian national

state meant to unite Serbs and

connect all predominantly Serb

territories? In other words, does it

reflect Yugoslavism or Serb

nationalism?

In his Opening

Statement, Milošević asserted that

the concept of Greater Serbia had

been invented for a propaganda

campaign launched by the

Austro-Hungarian Empire. When

Ottoman territory conquered by

Christian powers was redistributed

in 1878 by the Congress of Berlin,

BiH became an Austro-Hungarian

protectorate, to the great

consternation of the adjacent

emerging Kingdom of Serbia.28 Between

1878 and 1914, the relationship

between the Kingdom of Serbia and

the Austro-Hungarian Empire was

dominated by a rivalry over BiH

territory, which worsened when

Austro-Hungary annexed BiH in 1908.

Milošević cited that rivalry as the

reason the Austro-Hungarian Empire

had devised the “Greater Serbia”

concept, in order to accuse the

Kingdom of Serbia of expansionism.29

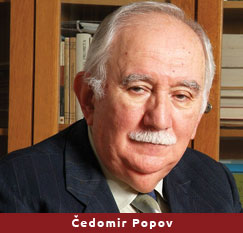

Čedomir Popov, a

Defence witness on the topic,

similarly claimed that the concept

of Greater Serbia was a consequence

of the power struggle for territory

between the Austro-Hungarian

monarchy and the Serbian kingdom. He

testified that the “myth” of Greater

Serbia ideology had been fostered as

a scare tactic, saying it:

...was nurtured and further

developed after the 1878 Berlin

Congress, acquiring the character of

a never-ending political and

religious campaign. The aim of this

campaign and the creation of the

myth was threefold; to prevent the

creation of a Serbian state within

its national borders, to conceal the

fact that Austria possessed some of

the Serbian and Balkan territories

and aspired to others, and to open

the routes to a Catholic missionary

campaign among the Orthodox

population of Southeastern Europe.

No effort was spared to spread the

myth about a Greater Serbian

threat...30

A number of

Defence witnesses repeated the

explanation Milošević and Popov

offered for the negative connotation

attached to the term Greater Serbia,

asserting it was a foreign invention

meant to discredit Serbia – an

emerging political power in the late

19th century – and prevent its

westward expansion.31 Defence Expert

Witness Kosta Mihailović also

brought up the role of two

well-known Serbian socialists,

Dimitrije Tucović (1881-1914) and

Svetozar Marković (1846-1876), who

he claimed contributed to a negative

appraisal of the term by applying it

to Serbian expansionist policies in

the second half of the 19th and

beginning of the 20th centuries, and

whose views he said were due to

“unyielding” ideological positions

that were “one-sided.”32

Čedomir Popov also

claimed that Načertanije had not

advocated aggression and therefore

should not be seen as having

instigated violence.33 Instead, Popov

argued, Garašanin’s plan focused on

integrating lands claimed by Serbia

on linguistic and religious grounds

– BiH, Northern Albania

(specifically Kosovo and Metohija),

and Montenegro – allowing Serbia to

unite all Serbs while leaving the

door open to other South Slavic

nations, including Bulgarians as

well as Croats from Slavonia,

Croatia, and Dalmatia. According to

Popov, Garašanin’s primary aim was

to liberate Serbs in the Balkans

from Ottoman rule, invoking their

“sacred historical right” based on

the pre-Ottoman legacy of the 14th

century Serbian state under Tsar

Dušan the Mighty.34

Asked by the

Prosecution to comment on the

proposition that a future Serbian

state as envisaged by Garašanin

would have been based on historic,

ethnic, religious, linguistic, and

geostrategic criteria and be led by

a Serb dynasty, Popov replied that,

indeed, Načertanije advocated the

national interest of Serbs, but he

said that similar nationalist and

irredentist35 conceptions “prevailed

throughout Europe in the 19th

century” and that “Serbs also had

the right to espouse such an idea.”36

In his Expert Report, Popov

characterised Greater Serbia

ideology as a myth that had been

“nourished, fostered, and spread” to

destabilise Serbia, which he claimed

in court was meant to enforce a

stereotype against Serbs as

hegemonic. When Milošević asked if

he in fact saw Serbia as a “victim

nation and a victim state,” Popov

said that he did.37 His answer

reflected the ideological framework

of Serb victimhood by which Serb

nationalist elites had mobilised

social action in Kosovo in the

1980s.

A History of Expansion of the

Serbian State by Force, 1912-1941

The Balkan Wars, 1912-1913

Serbian state

borders were redrawn twice during

the Balkan Wars, waged in 1912 and

1913, in which emerging Balkan

states fought the Ottoman Empire.

Serbia extended its borders south,

to Vardar Macedonia (a region now in

northern Macedonia) – also known as

Old Serbia because it was part of

the medieval Kingdom of Dušan the

Mighty – and into Kosovo and parts

of Sandžak. These conquests meant

that the Kingdom of Serbia

incorporated large numbers of

non-Serbs.38

In his Expert

Report, Defence witness Kosta

Mihailović wrote that Serbian

socialist Dimitrije Tucović had

asserted at the time of the Balkan

Wars that Serbia’s 1912 military

incursion into the northern parts of

Albania proved it was trying to

conquer that territory as well, with

aspirations to gain an outlet to the

Adriatic Sea. Mihailović contested

this, saying that it was in fact the

threat of the creation of a Greater

Albania that had spurred the start

of the Balkan Wars in the first

place.39 But it wasn’t just the

Albanians who had expansionist

ideas, and the danger of competing

irredentist or separatist claims had

been recognised in the late 19th

century by another Serbian

socialist, Svetozar Marković, who

drew attention to the hypocrisy of

Serbia for asserting the right to an

exclusive state in the Balkans but

denying that right to others.

Marković was also quoted by

Mihailović in his Report, though

Mihailović dismissed Marković’s

concerns by asserting that “it can

be reasonably assumed that he did

not know the real intentions of

[Serbian] policy.”40 In his Expert

Report, Defence witness Kosta

Mihailović wrote that Serbian

socialist Dimitrije Tucović had

asserted at the time of the Balkan

Wars that Serbia’s 1912 military

incursion into the northern parts of

Albania proved it was trying to

conquer that territory as well, with

aspirations to gain an outlet to the

Adriatic Sea. Mihailović contested

this, saying that it was in fact the

threat of the creation of a Greater

Albania that had spurred the start

of the Balkan Wars in the first

place.39 But it wasn’t just the

Albanians who had expansionist

ideas, and the danger of competing

irredentist or separatist claims had

been recognised in the late 19th

century by another Serbian

socialist, Svetozar Marković, who

drew attention to the hypocrisy of

Serbia for asserting the right to an

exclusive state in the Balkans but

denying that right to others.

Marković was also quoted by

Mihailović in his Report, though

Mihailović dismissed Marković’s

concerns by asserting that “it can

be reasonably assumed that he did

not know the real intentions of

[Serbian] policy.”40

The Serbian

conquest of territory in Kosovo

during the Balkan Wars involved

atrocities committed by Serbian and

Montenegrin soldiers, which some

observers saw as a systematic

attempt by the Serbian military to

alter the demographic balance of the

region in order to justify the

incorporation of Kosovo into the

Serbian state.41 On this issue,

Prosecution Expert Witness Budding

referred to the Carnegie Endowment’s

1914 Report of the International

Commission to Inquire into the

Causes and Conduct of the Balkan

Wars, which chronicled these

atrocities:

Houses and whole villages reduced to

ashes, unarmed and innocent

populations massacred en masse,

incredible acts of violence, pillage

and brutality of every kind – such

were the means which were employed

and are still being employed by the

Serbo-Montenegrin soldiery, with a

view to the entire transformation of

the ethnic character of regions

inhabited exclusively by Albanians.42

Defence witness

Čedomir Popov recognised that

atrocities had been committed by

Serbian forces; but he contended

that they were only in response to

attacks by Albanian units, which he

claimed were motivated by the

Albanian majority’s refusal to

accept Serbian authority.43

Slavenko Terzić,

who was called by the Defence as an

Expert Witness on the history of

Kosovo, notably omitted any

reference to the Balkan Wars in his

Expert Report. Yet, this particular

episode in the history of Kosovo and

Serbia is undeniably significant

because, in 1913 – after almost 500

years – Serbia repossessed Kosovo

from the retreating Ottoman Army and

incorporated its territory into the

expanding Kingdom of Serbia. In the

Prosecution’s cross-examination,

Terzić was asked why he hadn’t

mentioned these historical events,

including mass atrocities committed

against Kosovo Albanians by Serb

soldiers, in his Report. Terzić

accepted that the Carnegie

Endowment’s accounting of the extent

of the atrocities was probably

accurate, but said that they were

the expected consequences of war. He

rejected the Prosecution’s

suggestion that these atrocities

resulted from a Serbian government

plan to ethnically cleanse that

territory, concluding that such a

plan would have been implemented if

it existed.44 Terzić also failed to

mention the Serbian government’s

Kosovo colonisation programme in his

Report, though it was significant

for having offered certain economic

privileges to Serbs who were willing

to settle in Kosovo after 1913. As

Audrey Budding explained, the

purpose of the programme was to

change the ethnic composition of

Kosovo in favour of Serbs; but the

scheme never really worked and

Kosovo Albanians maintained a

majority.45

The First World War, the London

Treaty of 1915, and a Greater Serbia

In questioning

Čedomir Popov, the Prosecution

pressed the matter that some of the

first Greater Serbia ideologues had

advocated violence for the purpose

of unifying Serb-claimed

territories, asking about the early

20th-century organisation known as

both “Unification or Death”

(Ujedinjenje ili smrt) and the

“Black Hand” (Crna ruka). Popov

corroborated that, indeed, a member

of the organisation had assassinated

Aleksandar Obrenović – the last king

of the Obrenović Dynasty – in 1903.

Obrenović was known for having

cultivated a good relationship with

Austro-Hungary, then seen by Serb

nationalists as the major obstacle

to territorial expansion and a

specific challenge to territorial

aspirations in BiH. The same group

was also involved in the

assassination of Franz Ferdinand in

Sarajevo in 1914.46 In questioning

Čedomir Popov, the Prosecution

pressed the matter that some of the

first Greater Serbia ideologues had

advocated violence for the purpose

of unifying Serb-claimed

territories, asking about the early

20th-century organisation known as

both “Unification or Death”

(Ujedinjenje ili smrt) and the

“Black Hand” (Crna ruka). Popov

corroborated that, indeed, a member

of the organisation had assassinated

Aleksandar Obrenović – the last king

of the Obrenović Dynasty – in 1903.

Obrenović was known for having

cultivated a good relationship with

Austro-Hungary, then seen by Serb

nationalists as the major obstacle

to territorial expansion and a

specific challenge to territorial

aspirations in BiH. The same group

was also involved in the

assassination of Franz Ferdinand in

Sarajevo in 1914.46

Popov, who had

initially rejected the Prosecution’s

proposition that Greater Serbia

ideology was linked to violence, was

challenged to admit that terrorism

had indeed marked early attempts at

Serbian irridentism. He agreed that

the assassinations of King

Aleksandar and Archduke Franz

Ferdinand represented a shift toward

support for a more violent approach

by the Black Hand, which he

described as a paramilitary

organisation comprised of active

army officers of the Serbian Royal

Army. The objective of the group, he

said, was Serbia’s unification with

Serbs from Bosnia, an aim which he

claimed was fully supported by

Bosnian Serbs.47 Popov denied that the

assassination of Archduke Ferdinand

in 1914 was an expression of Greater

Serbia ambitions, though, asserting

that Bosnian Croats and Bosnian

Muslims were members alongside

Bosnian Serbs of Young Bosnia (Mlada

Bosna), the organisation that

actually carried out the

assassination. According to Popov,

Young Bosnia representatives sought

support from the Black Hand when

they were refused assistance from

the Serbian government.48 The

assassination was of course seen as

triggering the outbreak of the First

World War, during which the

Austro-Hungarian Empire

disintegrated and after which BiH

became part of a newly formed

Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

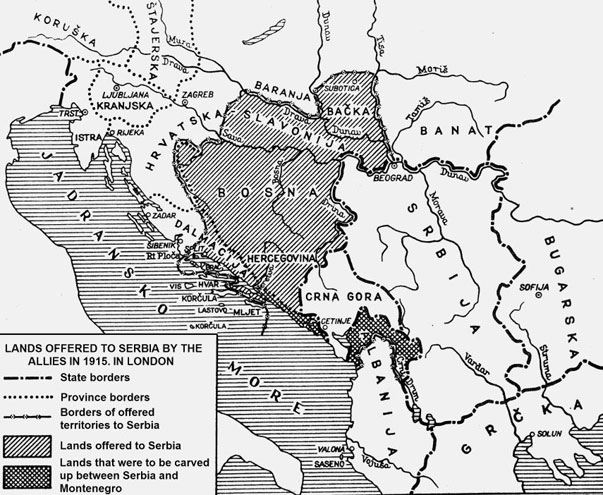

The Defence

position was that Serbs had never

aspired to form a Greater Serbia,

and had even rejected an enlarged

state when it was offered to them in

the 1915 London Treaty, preferring

instead to form a joint state with

the Slovenes and Croats. Milošević

introduced this notion in his

Opening Statement in August 2004,

stressing that the Serbs had

rejected the London Treaty despite

promises by the Allies to expand

Serbia to include territories in BiH

and Croatia:

To make the irony and absurdity even

greater and to make the lies and

injustice against the Serbian people

even worse...it is well known that

in 1915, the allies of Serbia, in

the so-called London Treaty, offered

Serbia, after winning the war, an

extension of its territory to Bosnia

and Herzegovina, parts of Dalmatia,

parts of Slavonia, and so on and so

forth. There are documents to show

all this. But Serbia did not do

this. Serbia instead embraced and

espoused Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes

alike from the former territories of

the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and

this is how the Kingdom of Croats,

Serbs and Slovenes was created,

later on to be called Yugoslavia.

This option taken by the Serbian

state to create a common state of

Yugoslavia rather than their own

state provided protection to our

Croatian and Slovenian brothers. We

protected them from territorial

fragmentation. And also, after they

had been part of a defeated state,

they became part of the winning

camp.49

Popov

contextualised the London Treaty

historically and politically, saying

that Austro-Hungary was the enemy

state and its territory had been

offered to Italy by the British in

order to get Italy involved in the

war on the side of the Allies.

According to Popov, Serbia was not

involved at all in these secret

negotiations; but the British had

agreed with Italy to the division of

a considerable part of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire, with the

rest going to either Serbia or a

common Serb, Croat, and Slovene

state.50 Further, Popov testified,

there were two London Treaty Maps,

the second of which dealt

specifically with Serbia. This

second map captured changes made to

the first, he said, and marked the

territories offered up to Serbia,

including Macedonian territory, as

compensation for the fact that

Serbia had lost Dalmatia to Italy.51

Popov explained that Serbia was also

offered Bosnia, Eastern Slavonia,

Bačka, Srem (Syrmia), and the part

of Dalmatia from north of Split up

to the Planck peninsula. He

commented that this was more

territory than Serbia ever

considered rightfully due.52

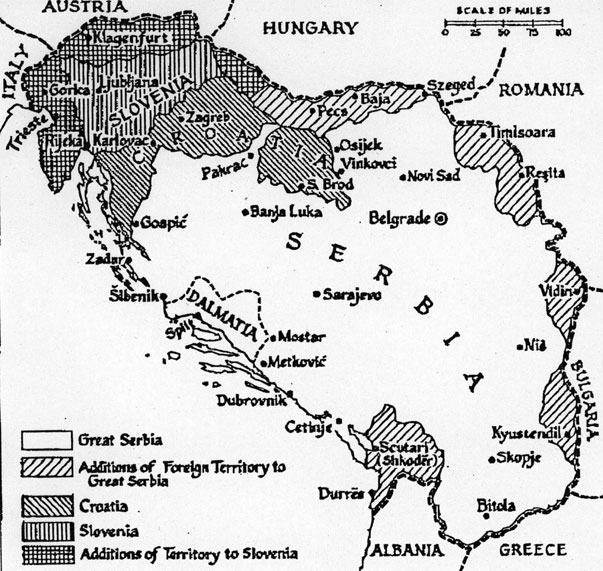

Map 2: London

Treaty Map showing land offered to

Serbia in 1905 by the Allied Forces

The First Yugoslavia or Greater

Serbia?

The contention of

the Defence was that the London

Treaty could have secured what was,

in effect, a Greater Serbia, but

that the Kingdom of Serbia had

rejected this prospect because it

chose instead to liberate Slovenes,

Croats, and Serbs who lived under

Austro-Hungarian rule. Popov

testified that Serbia’s war aims had

been laid out in the 1914 Niš

Declaration and favoured the

creation of a common Yugoslav state.53

However, Prosecution Expert Witness

Budding offered a different

interpretation of these events,

saying that Serbian political elites

in fact saw a common state as an

expanded Serbian state, not as a

Yugoslav state, which was then a

fundamentally new concept. Budding

testified that, at the time, the

notions of Greater Serbia and

Yugoslavia were synonymous, at least

in the minds of political decision

makers. According to her, the Niš

Declaration was a continuation of

Serbia’s pursuit of the unification

of all Serbs.54

Croat representatives in the

negotiations that preceded the

creation of the first Yugoslav state

advocated for a confederation;

though they eventually compromised

with the Serbs and established the

Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and

Slovenes under the Serb royal

dynasty of Karađorđević.55 As Audrey

Budding noted, there were Serbian

intellectuals who also saw the

importance of making a distinction

between a common state and the

expansion of Serbian domination, and

pushed for a federal state that

would decentralise power.56 In 1929,

the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and

Slovenes changed its name, becoming

the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, or the

First Yugoslavia. The state was

troubled by inter-ethnic relations

and growing Serbo-Croatian conflict.

Still, Serbia did engage in

political dialogue with Croats and

Slovenes and treated them as equal

nations; but its relationship with

other ethnic groups – the Bosnian

Muslims, the Macedonians, and the

Kosovo Albanians – remained

problematic.

An extreme example of how some Serbs

felt the non-Serb population should

be dealt with was found in yet

another document that remained

hidden away from the public for

years, at the Institute for Military

History in Belgrade, titled “The

Resettlement of the Arnauts”

(Iseljavanje Arnauta).57 The term

‘Arnauts’ was used to denote ethnic

Albanians, and the document

recommended moving the Albanian

population to Turkey and paying the

Turkish government as compensation

for resettlement costs. The proposal

was written by Vasa Ćubrilović, then

a junior historian who was known for

his Young Bosnia membership at the

time of the assassination of Franz

Ferdinand. Ćubrilović wrote the

document when he was an Assistant

Professor at the University of

Belgrade and presented it at a

session of the Serbian Cultural Club

in 1937. The Club was an

establishment for the elite,

including prominent Serb

politicians, high-ranking military

personnel, and intellectuals with

considerable influence over politics

and public opinion.

The Second World War and the

Historical Legacy of

Moljević’s

“Homogeneous Serbia”

The disintegration of the First

Yugoslavia in 1941 and its partition

among the Third Reich, Italy, and

neighbouring Nazi satellite states –

such as Hungary and Bulgaria –

redrew the map of Yugoslavia

considerably. Croatia was rewarded

with more territory for its alliance

with the Third Reich, extending its

borders to the east by annexing BiH

and Syrmia and reaching as far as

the suburban town of Zemun in the

vicinity of Belgrade. The Serbs, on

the other hand, were left by Nazi

Germany with a Serbian state that

was much smaller than the new

Independent State of Croatia

(Nezavasina država Hrvatska, or

NDH). The NDH was led by the extreme

right Ustasha movement, which

started exterminating Serbs, Roma,

Jews, and Communists in the

Jasenovac concentration camp in

order to change the ethnic

composition of the NDH in favour of

Croats.

In both Nazi Serbia and the NDH,

several Serb Chetnik guerrilla units

were active. The Chetnik guerrillas

under the command of Colonel Draža

Mihailović were considered by Allied

Forces to be a royal army and were

seen as an official resistance

movement until 1943, when Tito’s

victorious communist guerrillas,

known as the Partisans, became the

only recognised resistance movement

on the territory of the former

Kingdom of Yugoslavia. One of the

ideologues of the Chetnik guerrilla

movement was Stevan Moljević

(1888-1959), a lawyer from Banja

Luka who was a member of the Serbian

Cultural Club. In 1941, he authored

a pamphlet titled “Homogeneous

Serbia” (Homogena Serbia), which

revitalised Greater Serbia ideology

in the political and military

context of the Second World War and

the changing European State System.

Map 3: Moljević’s Map of Greater

Serbia. From Izvori Velikosrpske

Agresije,

page 146, Exhibit P807.

Asked by Milošević to comment on

Moljević’s contribution to the

Chetnik movement and Greater Serbia

ideology, Čedomir Popov testified

that it was Ustasha terror against

Serbs in the NDH that led to the

Chetnik movement. He described the

Chetniks as an incoherent group, but

said that, for some time, Draža

Mihailović’s movement indeed seemed

to have adopted Moljević’s ideas.

According to Popov, Moljević

envisaged a Greater Serbia that

would encompass even more territory

than offered by the London Treaty in

1915:

...Moljević envisaged that this

should be a homogenous Serbia from a

national point of view along the

following lines: The non-Serb

population will be allowed to leave

on their own or will be exchanged

for those Serbs which remain outside

this Greater Serbia. This programme

was rejected by the Chetniks

themselves. It was revised at the

so-called Sveti Sava Congress in the

village of Bar in January 1944 when,

under pressure exerted by the Allies

and because of the general feeling

that prevailed among the Allies, a

decision was made to create a

federative Yugoslavia with Serbia at

its centre.58

The historical importance of the

Moljević map for the development of

Greater Serbia ideology is in its

demarcation of a Western border

running from the Northern Croatian

town of Virovitica, through

Karlovac, to Karlobag in the South

of Croatia. The Prosecution asked

Popov to comment on Moljević’s map,

and in particular on the proposed

boundary, which would have left

Croatia as a very narrow strip of

territory beyond the projected

Virovitica-Karlovac-Karlobag (V-K-K)

line. Popov asserted that this

border was not accepted by all

Serbs,59 and indeed, that’s possible;

but the V-K-K line grew to be seen

by many as a potent and enduring

representation of Greater Serbia

ideology and proved relevant to the

war in Croatia in 1991.

The SANU MEMORANDUM - AN IDEOLOGICAL

BLUEPRINT FOR

SERBIA’S POLITICS

UNDER SLOBODAN MILOŠEVIĆ?

It is hard to find any literature on

the Yugoslav crisis that does not

make note of connections between the

SANU Memorandum and the political

programme introduced by Milošević,

but there are various perspectives

on the nature of these connections.

One view is that the Memorandum

served as the “blueprint” for

Milošević’s war policies.60 Another is

that it more generally advocated “a

reformed federation.”61 And

alternative to both of these is the

view that the Memorandum can be seen

as an “explicit post-Yugoslav

Serbian national program.”62 Some

authors argue that the Memorandum

did not advocate the dissolution of

Yugoslavia, the creation of a

Greater Serbia, or ethnic cleansing,

and that no connection has been

established between the authors of

the Memorandum and Milošević.

According to some authors at the

time of the Memorandum’s

publication, Milošević’s views were

no different from other Serbian

communist leaders.63 Nonetheless, some

ICTY witnesses talked in court about

the importance of the SANU

Memorandum, and the polarised

narratives that unfolded followed

the fault lines of pre-existing

scholarly debate on the importance

of the Memorandum. And once again,

this courtroom narrative was

significantly shaped by Milošević’s

active participation in court,

discussing his position on the SANU

Memorandum with several of its

authors who appeared as Defence

witnesses.64

In 1985, Serbian political leaders

approved a proposal by members of

the Serbian Academy of Sciences and

Arts (SANU) that they contribute to

solving the profound social,

economic, and political crises

facing Yugoslavia and the Republic

of Serbia at the time. Stambolić

consented to the endeavour because

he firmly believed that science

should be part of those efforts. The

SANU leadership organised several

expert teams, each of which analysed

different aspects of the crisis and

made proposals for how to resolve

them.65 The product of this work – the

SANU Memorandum – took Stambolić by

surprise, and he qualified it as an

“obituary for Yugoslavia.”66 He felt

that the recommendations advanced in

the document were contrary to the

interests of Serbs in Yugoslavia,

whom he felt were best served by a

common state. Stambolić was one of

the first communist officials to

criticise the Memorandum in public,

warning against the dangers of

attempts to “unite” Serbs on the

ruins of Yugoslavia, and saying

presciently that this would lead to

conflict with other Yugoslav nations

and with the rest of the world. In 1985, Serbian political leaders

approved a proposal by members of

the Serbian Academy of Sciences and

Arts (SANU) that they contribute to

solving the profound social,

economic, and political crises

facing Yugoslavia and the Republic

of Serbia at the time. Stambolić

consented to the endeavour because

he firmly believed that science

should be part of those efforts. The

SANU leadership organised several

expert teams, each of which analysed

different aspects of the crisis and

made proposals for how to resolve

them.65 The product of this work – the

SANU Memorandum – took Stambolić by

surprise, and he qualified it as an

“obituary for Yugoslavia.”66 He felt

that the recommendations advanced in

the document were contrary to the

interests of Serbs in Yugoslavia,

whom he felt were best served by a

common state. Stambolić was one of

the first communist officials to

criticise the Memorandum in public,

warning against the dangers of

attempts to “unite” Serbs on the

ruins of Yugoslavia, and saying

presciently that this would lead to

conflict with other Yugoslav nations

and with the rest of the world.

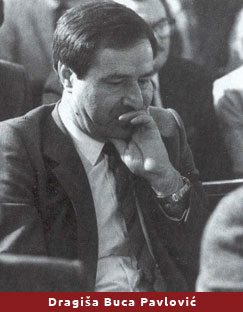

In the months following a ‘leaked’

disclosure of the Memorandum in

1986, it was the topic of discussion

at all Party forums. Unlike fellow

politicians Stambolić and Dragiša

Pavlović, Milošević remained silent;

he was diligent about not speaking

against the Memorandum in public,

though he did allow for some

criticism of it by others in less

public settings.67 And while he never

commented on the contents of the

Memorandum itself, Milošević

defended the Academy on a number of

different occasions, saying that it

was only natural that an institution

of the highest intellectual and

moral standards would deal with

solving complex issues like the

Yugoslav crisis.68

The Prosecution mentioned the SANU

Memorandum only briefly in its

Opening Statement, referring to the

threat it had alleged faced Serbs in

Kosovo and Croatia and how that

rhetoric contributed to creating

fear among Serbs.69 But the Memorandum

kept cropping up in evidence as the

trial went on, progressively

revealing its importance as an

apparent blueprint for the political

programme that had been implemented

by Milošević. The central arguments

in the Memorandum were based on the

notion that economic and political

systems had suffered negative

consequences as a result of the 1974

Yugoslav Constitution, by which the

Federation had become a

confederation. According to the

Memorandum’s authors, the 1974

Constitution made the Yugoslav

political system “a textbook case of

inefficiency” and they argued that

the only way out of the crisis was

to abandon the political and

economic systems that were based on

that Constitution.70 They also

identified three additional issues

confronting Serbia in the

Federation: its economic

underdevelopment, its unresolved

relationship with the state and the

provinces, and “the genocide in

Kosovo.”71 These and other very

serious charges painted a dim

picture of life for Serbs and

included accusations that the Serb

population in Kosovo and Croatia had

been threatened by “physical,

political, legal, and cultural

genocide” that had directly affected

the ethnic balance in the Yugoslav

Federation.72 The conclusion of the

Memorandum’s authors was that the

root of both the Yugoslav crisis and

the Serbian crisis lay in

Yugoslavia’s decentralisation. They

called for transforming Yugoslavia

and referred, though only in

passing, to the possibility of its

collapse.73

The Memorandum’s one-sided emphasis

on Serbian victimisation was

reflected in all forms of public

debate in the years that followed.

But Prosecution Expert Budding

suggested that the content of the

Memorandum was not its most relevant

feature; she considered it most

significant for the way in which it

had been introduced to the public

and how it had polarised Serbian

political leadership.74 Budding also

drew attention to the fact that,

unlike previous critics of the 1974

Constitution, the authors of the

SANU Memorandum catalogued

pre-existing grievances together

with one important and

groundbreaking new inference – that

Serbs might be able to do without

Yugoslavia.75

Authors of the Memorandum Appear as

Defence Witnesses

In his Opening Statement in February

2002, Milošević said that the

indictments against him accused not

just him but the whole Serb nation,

beginning with the Serbian

intelligentsia and members of the

SANU. He defended the SANU and the

Memorandum, saying that Serbian

academics had responsibly and

authoritatively described the

situation in Kosovo.76 Though he had

hardly ever spoken publicly of the

Memorandum and it was difficult to

prove that he had even read it, its

role in shaping his ideology became

clear when Milošević called some of

its most prominent authors to the

stand for his Defence. The fact that

they were asked to appear spoke

volumes despite his reticence.77

Professor Kosta Mihailović, an

economist who was among the

Memorandum’s authors, was an advisor

to Milošević at all major

negotiations in the early 1990s; he

testified as an expert witness on

the topic of Serbia’s economic

sluggishness in the First Yugoslavia

(1918-1941), and also about the

Memorandum and Milošević’s attitude

toward it. In 1993, Mihailović had

co-authored a book titled Memorandum

of the Serbian Academy of Sciences

and Arts: Answers to Criticisms in

which he and Vasilije Krestić – a

Professor of History and fellow SANU

member who was responsible for the

part of the Memorandum that

addressed the history of genocide

against Serbs – explained why and

how the Memorandum was written.

While Mihailović confirmed in his

testimony that there was indeed a

link between the ideas in the

Memorandum and the views of

Milošević on legal, political, and

economic aspects of the crisis, in

the book, he and Krestić denied that

this was anything but coincidental: Memorandum and Milošević’s attitude

toward it. In 1993, Mihailović had

co-authored a book titled Memorandum

of the Serbian Academy of Sciences

and Arts: Answers to Criticisms in

which he and Vasilije Krestić – a

Professor of History and fellow SANU

member who was responsible for the

part of the Memorandum that

addressed the history of genocide

against Serbs – explained why and

how the Memorandum was written.

While Mihailović confirmed in his

testimony that there was indeed a

link between the ideas in the

Memorandum and the views of

Milošević on legal, political, and

economic aspects of the crisis, in

the book, he and Krestić denied that

this was anything but coincidental:

The insinuation that Slobodan

Milošević was carrying out a

national agenda contained in the

Memorandum is a pure fabrication.

This claim was inspired by the

course of events and the

anti-Serbian propaganda’s need to

keep the official and unofficial

organs of Serbia under a constant

barrage of accusations.... Another

charge against the Memorandum is

that it served as a springboard for

Slobodan Milošević’s policies. There

is nothing strange in the fact that

he may have seen some of the

problems and solutions in the same

or similar light as the document in

question. It is more likely that he

did not learn about the existence of

these problems for the first time

from the Memorandum, but that he

found in it confirmation for some of

his own personal observations.78

The booklet also shed light on the

few criticisms Milošević had

actually expressed about the

Memorandum:

...some facts suggest that he was

critical of the authors of the

Memorandum more out of compliance

with the party discipline than out

of personal conviction. During the

political witch hunt in Serbia, it

was noted that his criticisms were

rare and relatively mild. After

assuming the key political position

in Serbia, finding himself able to

influence the direction of political

action, he stopped the campaign

against the Memorandum. The

importance of this is not diminished

by the fact that he had stopped the

attacks against the Serbian Academy

as part of the democratisation of

society, an official change of heart

toward the intelligentsia, freedom

of speech and the introduction of a

multiparty system.79

The publication – or rather, public

disclosure – of the Memorandum had

been the subject of controversy

itself. The authors maintained that

it was leaked without their

knowledge. Others claimed that it

was deliberately leaked in order to

generate interest among Serbs for

the topics it discussed. A second

controversy centred on the version

of the text that was published. Was

the 1986 publication an unfinished

version as the authors claimed? Or

was this label used as a way to

brush off and deter criticism by

claiming that this first published

version was not the final,

authorised text?

Kosta Mihailović addressed this

point in his testimony, saying that

uproar over the Memorandum was

unjustified, and all the more so

because the version that was leaked

was unedited. He explained that

there were initially twenty copies

printed, of which sixteen were meant

for the contributors and members of

the commission, along with copies

for each of three consultants –

Dobrica Ćosić, Ljuba Tadić, and

Jovan Đorđević – leaving one copy

undistributed.80 Mihailović stressed

that this unauthorised draft of the

text was not approved as the final

version.

In response, the Prosecution

produced an analysis that compared

the leaked “unauthorised” version

from 1986 with the official version

published in Memorandum of the

Serbian Academy of Sciences and

Arts: Answers to Criticisms seven

years later. Only six small

differences existed between the two,

and mostly in language, not in

substance.81 Mihailović readily

accepted the Prosecution’s findings

and stated that he was personally

aware of only one change in the

section on economics that he

authored, which appeared to be the

result of a typing error. He

admitted that if there were any

differences between the two

versions, they could be only minor.

On the question of the leak, he

insisted that the document had been

leaked without the authors’

involvement, and that their

intention was never to make it

public.82 Mihailović attributed the

leak to Professor Jovan Đorđević’s

son-in law, a journalist at the

daily Večernje Novosti who allegedly

spotted the draft text at Đorđević’s

house and published it in the

newspaper.83 This explanation is

unlikely, though, as it was quite

inconceivable in the communist

system that any journalist would

dare, or be able, to publish such an

explosive text without consent of

their editor-in-chief and the

backing of at least a handful of

politicians. Both the political

system and the media were tightly

controlled by the League of

Communists.

The publication of the Memorandum

led to a buying frenzy, with

photocopies sold at every street

corner in Belgrade. The Prosecution

suggested that this leak had been

manipulated and compared the

clandestine nature of it to the

treatment of Načertanije, which was

written in 1844 but kept secret

until it was published for general

consumption for the first time in

1906. But Mihailović rejected the

Prosecution’s suggestion that

secrecy had helped generate popular

interest in either of those

documents.84 He insisted that the

Memorandum was meant to be a

non-public document, written to

animate the political establishment.85

In his Expert Report, Prosecution

Expert Witness on propaganda Renaud

de la Brosse qualified the

publishing of the Memorandum as a

“deliberate leak” and suggested that

its appearance in a daily newspaper

in several instalments could not

have occurred without the approval

of at least some members of the LC.86

Just how broad support for the

Memorandum was in Serbia became

apparent at the Eighth Session of

the Central Committee, held in

September 1987, when it divided the

Serbian leadership into Stambolić

and Milošević blocs. A majority of

delegates supported Milošević

against Stambolić and Dragiša

Pavlović, the two most vocal critics

of the Memorandum, and the standoff

that ensued exposed proponents and

opponents of a new policy course.87

The wave of political purges that

followed allowed Milošević to

quickly rid the government of anyone

who did not readily accept this new

political direction.88 In his Expert Report, Prosecution

Expert Witness on propaganda Renaud

de la Brosse qualified the

publishing of the Memorandum as a

“deliberate leak” and suggested that

its appearance in a daily newspaper

in several instalments could not

have occurred without the approval

of at least some members of the LC.86

Just how broad support for the

Memorandum was in Serbia became

apparent at the Eighth Session of

the Central Committee, held in

September 1987, when it divided the

Serbian leadership into Stambolić

and Milošević blocs. A majority of

delegates supported Milošević

against Stambolić and Dragiša

Pavlović, the two most vocal critics

of the Memorandum, and the standoff

that ensued exposed proponents and

opponents of a new policy course.87

The wave of political purges that

followed allowed Milošević to

quickly rid the government of anyone

who did not readily accept this new

political direction.88

The Influence of the SANU Memorandum

on

Post-Communist Serbian State

Ideology

The SANU Memorandum reflected

criticism that had been expressed by

Serbian elites since the adoption of

the 1974 SFRY Constitution, which

was seen by some as disadvantageous

to Serbia because it partitioned the

republic into three

political-administrative parts by

making the provinces of Kosovo and

Vojvodina federal units. To

contextualise the aims of the 1974

Constitution, Audrey Budding

explained that in the 1950s and

1960s, Serbia had dominated the

Kosovo political scene. At the time,

Aleksandar Ranković, a Serbian

communist functionary who held

significant influence, made

centralisation of the Federation and

of Serbia a dominant political goal.

Ranković had risen to the highest

political ranks by serving as the

first Head of the Communist State

Security Service (UDBA). Even when

he moved on to more visible

political functions – making an

impressive political career in

post-WWII Yugoslavia by becoming

Vice-President of the Federation –

he continued to control the Secret

Service. Ranković was eventually

dismissed from the Party in 1966

for, among other things, disloyalty

to Tito and espousing Serbian

unitarism. He was accused of abusing

the power he had over the security

services, including by allegedly

putting Tito himself under

surveillance, as well as for

unlawful use of the police in

Kosovo. Some of his contemporaries

later claimed that Ranković had been

loyal to Tito but had gotten himself

into trouble trying to secure his

position as Tito's heir.

Nonetheless, Ranković was labelled a

Stalinist, a centralist, and a Serb

nationalist, and the post-Ranković

period brought democratisation and

decentralisation of the Party and

the state, with changes in the

balance of power in Kosovo in favour

of its Kosovo Albanian majority.89

Addressing the criticism by Serbian

intellectual elites of the

Constitution of 1974, Budding

explained that the first changes to

the status of Kosovo and Vojvodina

came with three sets of

constitutional amendments passed

between 1968 and 1971, in which

Serbia’s autonomous provinces were

given greater independence from

Serbia and greater decision-making

power at the federal level. The most

radical of these changes were passed

in 1971, when a twenty-three member

collective federal presidency was

introduced, with three

representatives from each republic

and two from each province, and Tito

as the 23rd member. The 1974

Constitution reduced that number to

nine: one representative from each

republic and province, and Tito as

the ninth member.90 The composition of

the Presidency changed once again in

1980, after Tito’s death, to an

eight-member body, since no one

replaced Tito as the singular head

of state.

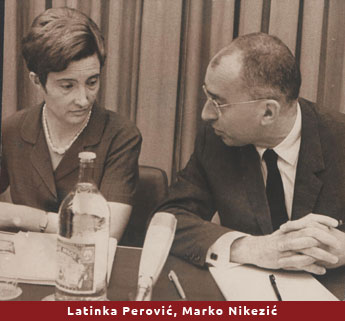

Serbian communist liberals led by

Marko Nikezić and Latinka Perović,

who were in power until 1972,

welcomed decentralisation. Still,

many Serbian intellectuals and

sitting communist politicians

resisted the changes. According to

Budding, there were two groups of

opponents to decentralisation:

Yugoslav unitarists were ardent

Yugoslavists who saw

decentralisation as weakening the

original Yugoslav concept; and the

‘particularists’ had been early

proponents of Yugoslavism but sought

unity in Serbdom when they felt a

common state was being undermined.

This latter group remained

preoccupied with the unity of the

Serbs, rejecting the idea that they

should be divided among different

federal units, and began raising

concerns about the rights of Serbs

outside Serbia.91 One of the most

articulate critics of

decentralisation was Dobrica Ćosić,

who was still a member of the Party

and of the communist establishment

at the time. When Ćosić became

marginalised for his criticism of

decentralisation, he moved his

activities to the Serbian Literary

Cooperative, the so-called Zadruga,

of which he was elected president.92 Budding, there were two groups of

opponents to decentralisation:

Yugoslav unitarists were ardent

Yugoslavists who saw

decentralisation as weakening the

original Yugoslav concept; and the

‘particularists’ had been early

proponents of Yugoslavism but sought

unity in Serbdom when they felt a

common state was being undermined.

This latter group remained

preoccupied with the unity of the

Serbs, rejecting the idea that they

should be divided among different

federal units, and began raising

concerns about the rights of Serbs

outside Serbia.91 One of the most

articulate critics of

decentralisation was Dobrica Ćosić,

who was still a member of the Party

and of the communist establishment

at the time. When Ćosić became

marginalised for his criticism of

decentralisation, he moved his

activities to the Serbian Literary

Cooperative, the so-called Zadruga,

of which he was elected president.92

The most serious and explicitly

political condemnation of the

decentralisation amendments came

from the Law Faculty of the

University of Belgrade. At a Faculty