|

Case

study

1

The purpose of

this paper is to analyse how the

political leadership of the

(Socialist) Republic of Serbia

(henceforth the Serbian leadership)

achieved control over the Yugoslav

People’s Army (JNA) in the period

between the late 1980s and early

1992. This control was ‘formally’

established on 3 October 1991, when

the four Serbian and Montenegrin

members of the Presidency of the

Socialist Federal Republic of

Yugoslavia (SFRJ) assumed the right

to act as the provisional SFRJ

Presidency and to give orders to the

JNA, a decision accepted by the JNA

General Staff. However, this control

was in fact established on an

informal basis much earlier.

Although the eight-member SFRJ

Presidency was the Supreme Commander

of the JNA to which the General

Staff of the JNA was formally

subordinate, the Federal Secretary

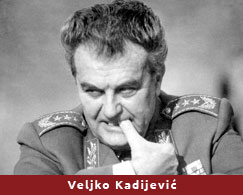

for People’s Defence, Army General

Veljko Kadijević, the most senior

officer of the JNA, came during the

period 1990-91 to treat only its

members from Serbia and Montenegro

as those to whom he had to report

and with whom he had to confer over

strategy. In practise, this meant

that he viewed the Serbian political

leadership in the persons of Serbian

President Slobodan Milošević and

Serbian member of the SFRJ

Presidency Borisav Jović as the

politicians to whom he was

responsible.

Serbia’s political

leadership and the JNA entered the

year 1990 as allies sharing a common

opposition to Kosovo Albanian

autonomism and to Slovenian moves

toward sovereignty, and the common

goal of recentralisation of the

SFRJ. The character of this alliance

was thrown into question in the

spring of that year, however, as the

Serbian leadership abandoned support

for a unified Yugoslavia. They

adopted instead the plan of

“expelling” Slovenia and a truncated

Croatia from the Yugoslav Federation

and establishing a de facto Great

Serbia. Kadijević was in close

contact with Jović and Milošević

throughout this period and was

informed by them of their. Although

Kadijević was ready to embrace their

“Great Serbian” goals, his own

preference was for a military coup

d’état to overthrow the political

leaderships of Slovenia and Croatia

as well as the SFRJ Presidency and

government in order to restore a

centralised, unified Yugoslav state.

He and Chief of the General Staff

Blagoje Adžić wavered between a

“Yugoslav” and a “Great Serbian”

orientation until the second half of

1991. The Serbian and JNA

leaderships were therefore allies

with overlapping but different

concepts of how to respond to the

Yugoslav crisis. The question of a

Great Serbia or a unified Yugoslavia

under military rule was the question

also of whether the Serbian

leadership or the JNA would be the

senior partner in the alliance.

This is a study of

the relations at the very top of the

political and military pyramid. It

focuses in particular on the

relationship between Milošević,

Jović, Kadijević and Adžić, and

relies in particular on the

published memoirs and interviews of

the latter three and of other senior

JNA officers, of which the diary of

Borisav Jović is by far the most

important.1

The origins of the SKS/SPS-JNA

alliance

The origins of the

alliance between the League of

Communists of Serbia (SKS),

subsequently the Socialist Party of

Serbia (SPS)2 and the JNA date back

to long before Milošević’s rise to

power. There was overlap between the

cadres of the two organisations,

personified by Army General Nikola

Ljubičić, who was said to have been

“person number two” in Yugoslavia on

the eve of Tito’s death.3 Ljubičić

served as Federal Secretary for

People’s Defence in 1967-82,

President of the Presidency of the

Socialist Republic of Serbia in

1982-84 and SFRJ Presidency member

for Serbia in 1984-89. In the

opinion of Admiral Branko Mamula,

his successor as SFRJ Defence

Secretary, during the 1980s Ljubičić

strove to control the links between

the JNA and SKS leaderships.4 He

played the decisive role in

Milošević’s assumption of control

over the SKS in 1987. Another such

figure was Colonel-General Petar

Gračanin, JNA Chief of Staff in

1982-85, President of the Presidency

of Serbia in 1987-89, Yugoslav

Minister for Internal Affairs in

1989-92 and a member of the SPS

General Council since 1996. A third

was General Aleksandar Janjić, who

served as JNA commander in Niš and

president of the Partisan veterans’

association for Serbia. Ljubičić,

Gračanin and Janjić were, according

to Mamula, Milošević’s three key

supporters in the JNA’s highest

echelons from 1987.5 The origins of the

alliance between the League of

Communists of Serbia (SKS),

subsequently the Socialist Party of

Serbia (SPS)2 and the JNA date back

to long before Milošević’s rise to

power. There was overlap between the

cadres of the two organisations,

personified by Army General Nikola

Ljubičić, who was said to have been

“person number two” in Yugoslavia on

the eve of Tito’s death.3 Ljubičić

served as Federal Secretary for

People’s Defence in 1967-82,

President of the Presidency of the

Socialist Republic of Serbia in

1982-84 and SFRJ Presidency member

for Serbia in 1984-89. In the

opinion of Admiral Branko Mamula,

his successor as SFRJ Defence

Secretary, during the 1980s Ljubičić

strove to control the links between

the JNA and SKS leaderships.4 He

played the decisive role in

Milošević’s assumption of control

over the SKS in 1987. Another such

figure was Colonel-General Petar

Gračanin, JNA Chief of Staff in

1982-85, President of the Presidency

of Serbia in 1987-89, Yugoslav

Minister for Internal Affairs in

1989-92 and a member of the SPS

General Council since 1996. A third

was General Aleksandar Janjić, who

served as JNA commander in Niš and

president of the Partisan veterans’

association for Serbia. Ljubičić,

Gračanin and Janjić were, according

to Mamula, Milošević’s three key

supporters in the JNA’s highest

echelons from 1987.5

The sense of

“common purpose” between the

political and military elites was

cemented by at least three factors:

1) The system of

“All-People’s Defence” implemented

in Yugoslavia after 1968 assumed the

mobilisation of the entire Yugoslav

population in the struggle against

an external invader and required the

military and Party authorities to

cooperate in this task. The Yugoslav

armed forces were divided between

the JNA and the Territorial Defence

(TO). The latter was organised on a

decentralised basis with TO staffs

for each republic, province and

municipality, commanded by reserve

JNA officers but organised and

funded by the corresponding bodies

of the government and League of

Communists of Yugoslavia (SKJ). This

system necessitated close

coordination in defence preparations

between the SKJ and the JNA,

facilitated by the fact that the SKJ

possessed its own organisation

within the JNA to ensure that the

latter acted according to its party

programme. According to Ljubičić,

writing in the 1970s:

“The organisation of the League of

Communists within the Yugoslav

People’s Army is a part of the

League of Communists of Yugoslavia.

The Communists within the JNA

endeavour that the organisation of

the League of Communists in the JNA

always be competent ideologically

and in action to participate in

advancing the politics of the SKJ,

particularly in the field of

national defence, and that the

adopted politics be creatively and

consistently realised through the

closest conjunction with other

organisations of the League of

Communists.”6

Thus for example

on 19 April 1985 Slobodan Milošević,

President of the City Committee of

the SKS for Belgrade and Bogdan

Bogdanović, President of the

Belgrade City Assembly held talks

with Federal Secretary for People’s

Defence Branko Mamula concerning

defence preparations in Belgrade and

economic cooperation between the

city and the JNA.7

2) The SKS and the

JNA during the 1970s and 80s were

united by their shared fear and

resentment of Kosovo Albanian

nationalism and autonomism. The JNA

General Staff responded to the 1981

uprising of Kosovo Albanians by

disbanding the predominantly

Albanian Kosovo TO and dismissing

80-90% of its troops on suspicion

that they had supported the rebels.

The General Staff furthermore

strengthened the JNA forces in

Kosovo to guard against the possible

participation of both Albania and

the Kosovo Albanians in a foreign

attack on Yugoslavia.8

3) The JNA officer

corps was disproportionately Serbian

in composition and increasingly so

from the 1980s. In 1987, at the time

of Milošević’s seizure of power

within the SKS, 60% of the JNA

officer corps was Serb, according to

Mamula.9 This imbalance was

heightened by the fact that during

the 1980s most members of the

Partisan generation in the top ranks

of the JNA retired from active

service. This generation had been

genuinely multinational and

Yugoslav-oriented and included, for

example, all four colonel-generals

of Muslim nationality.10 The new

generation of active JNA generals

had not participated in the

multinational Partisan movement and

its political and national

consciousness was therefore much

narrower.

However, so far as

the highest ranks were concerned it

was the Serbs from the central

Croatian regions of Lika, Kordun and

Banija – the location subsequently

of the “Serbian Republic of Krajina”

– and Bosanska Krajina (Western

Bosnia), rather than from Serbia,

who were most over-represented.11 This

reflected the numerically

disproportionate role that Serbs

from Croatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina

played in the Partisan movement of

1941-1945. Of the last three

generals to hold the post of full or

acting SFRJ Secretary for People’s

Defence (the top position in the

JNA) Branko Mamula (1982-88) and

Veljko Kadijević (1988-92) were

Serbs from Croatia12 while Blagoje

Adžić (1992) was a Serb from

Bosnia-Herzegovina. This meant that

while the JNA command could ally

with the Serbian leadership on a

“Great Serbian” basis, its outlook

was somewhat different. However, so far as

the highest ranks were concerned it

was the Serbs from the central

Croatian regions of Lika, Kordun and

Banija – the location subsequently

of the “Serbian Republic of Krajina”

– and Bosanska Krajina (Western

Bosnia), rather than from Serbia,

who were most over-represented.11 This

reflected the numerically

disproportionate role that Serbs

from Croatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina

played in the Partisan movement of

1941-1945. Of the last three

generals to hold the post of full or

acting SFRJ Secretary for People’s

Defence (the top position in the

JNA) Branko Mamula (1982-88) and

Veljko Kadijević (1988-92) were

Serbs from Croatia12 while Blagoje

Adžić (1992) was a Serb from

Bosnia-Herzegovina. This meant that

while the JNA command could ally

with the Serbian leadership on a

“Great Serbian” basis, its outlook

was somewhat different.

Members of the

General Staff in the 1980s believed

that the semi-confederal character

of the Yugoslav state gravely

weakened the JNA. Consequently, in

1987 it adopted measures to

strengthen the JNA vis-à-vis the

republics. The six armies were

replaced by three army groups, in

Kadijević’s words, “whose

territorial division completely

disregarded the administrative

frontiers of the republics and

provinces.”13 The staffs of the

republican and provincial TOs were

subordinated to the staffs of the

three army groups, rather than to

the Supreme Command, and the staffs

of the TO zones to the staffs of the

JNA corps. In this way, republican

influence over both the JNA and the

TO was reduced. According to

Kadijević, ‘It is certain that this

solution, at least up to a point,

removed the already developed

control of the Republics and

Provinces over their Territorial

Defences and greatly reduced their

already legalised influence over the

JNA.’14 In Mamula’s words, ‘This meant

excluding the Republican leaderships

from the system of commanding the

armed forces and armed struggle.’15

The TO forces were

also greatly reduced in size. For

example, the TO of the Socialist

Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina was

reduced from 293,272 soldiers at the

start of 1987 to 86,362 by the end

of 1991. This reduction was made

disproportionately at the expense of

Muslim- or Croat- rather than

Serb-majority okrugs. Thus, for

example, during 1988 the TO for the

Muslim-majority Sarajevo okrug was

reduced by 42.3%, but the TO for the

Serb-majority Banja Luka okrug was

reduced by only 16%.16

The political

outlook, style and methods of

Kadijević and Adžić on the one hand

and Milošević and Jović on the other

were fundamentally different. The

JNA commanders were conservatives

who preferred a recentralised

Yugoslav federation to any radical

overhaul of the Titoist order, while

the Serbian leaders were radicals

prepared to adopt radical methods to

overturn the status quo. According

to Dizdarević, during the late 1980s

Kadijević viewed Milošević’s method

of mass popular mobilisation to

achieve changes at the state level

as unacceptable.17 However, political

developments in this period brought

the leaderships of the JNA and

Serbia together. In 1988, the

General Staff found itself it

conflict with the political

leadership of the Socialist Republic

of Slovenia over the affair of the

“Ljubljana Four”. This conflict

rapidly merged with Serbia’s own

conflict with Slovenia.18 During 1989,

Milošević’s leadership in Serbia

suppressed the autonomy of Kosovo

and Vojvodina and pressed for the

recentralisation of the Yugoslav

state. The Slovenian leadership

reacted by solidarising with the

Kosovo Albanians and introducing, in

September, constitutional changes

designed to give Slovenia

sovereignty within Yugoslavia.19

In January 1989

the Yugoslav and Republican

presidencies discussed possible

candidates for the post of SFRJ

Prime Minister (President of the

Federal Executive Council - SIV) to

replace Branko Mikulić. Kadijević

proposed Milošević for the post and

was authorised by the then President

of the SFRJ Raif Dizdarević, himself

a retired JNA general, to speak with

Milošević about this possibility.

Dizdarević claims in his memoirs

that he favoured Milošević as SFRJ

Prime Minister because he believed

that the latter would create less

trouble and be more easily

controllable if transferred from the

Serbian to the Federal leadership.20

Kadijević, by contrast, wanted

Milošević to assume the post because

‘Assessing that the Yugoslav Federal

leadership lacked, among other

things, a strong and capable

political figure of a Yugoslav

orientation and simultaneously

estimating that in the existing

conglomerate of Federal institutions

the SIV would be able to achieve the

most, after the resignation of

Branko Mikulić I proposed Slobodan

Milošević for President of the SIV.’

However, ‘Milošević and the Serbian

leadership had a different

assessment. There were no

differences in goals, but there were

differences over how to achieve

them. Namely, the positions of the

Serbian leadership and Milošević

were that it was necessary to secure

the unity of Serbia after the

constitutional changes which were

made and in that way to contribute

to the stability of Yugoslavia and

that for that reason Milošević

should remain in Serbia.’21 In January 1989

the Yugoslav and Republican

presidencies discussed possible

candidates for the post of SFRJ

Prime Minister (President of the

Federal Executive Council - SIV) to

replace Branko Mikulić. Kadijević

proposed Milošević for the post and

was authorised by the then President

of the SFRJ Raif Dizdarević, himself

a retired JNA general, to speak with

Milošević about this possibility.

Dizdarević claims in his memoirs

that he favoured Milošević as SFRJ

Prime Minister because he believed

that the latter would create less

trouble and be more easily

controllable if transferred from the

Serbian to the Federal leadership.20

Kadijević, by contrast, wanted

Milošević to assume the post because

‘Assessing that the Yugoslav Federal

leadership lacked, among other

things, a strong and capable

political figure of a Yugoslav

orientation and simultaneously

estimating that in the existing

conglomerate of Federal institutions

the SIV would be able to achieve the

most, after the resignation of

Branko Mikulić I proposed Slobodan

Milošević for President of the SIV.’

However, ‘Milošević and the Serbian

leadership had a different

assessment. There were no

differences in goals, but there were

differences over how to achieve

them. Namely, the positions of the

Serbian leadership and Milošević

were that it was necessary to secure

the unity of Serbia after the

constitutional changes which were

made and in that way to contribute

to the stability of Yugoslavia and

that for that reason Milošević

should remain in Serbia.’21

Up until January

1990 Borisav Jović as Serbia’s

representative on the SFRJ

Presidency, Slobodan Milosević as

President of the Presidency of the

Socialist Republic of Serbia, Veljko

Kadijević as SFRJ Secretary for

People’s Defence and Petar Gračanin

as SFRJ Secretary for Internal

Affairs tended to see eye to eye

over policy. They consulted with

each other and coordinated their

political moves.22 All four were Serbs

and all four were Communist

opponents of political

liberalisation, Federal

decentralisation and Kosovo Albanian

and Slovenian autonomism. On 1-12

August Kadijević, Jović, Milošević

and Bogdan Trifunović (chairman of

the SKS Central Committee) went on

holiday together, along with their

respective families. Jović writes

that on this occasion “I see the

views of the JNA and Veljko

Kadijević regarding the future of

Yugoslavia: 1) he will defend it at

any price; 2) there must be an

efficient federal state; 3) he

accepts the free-market orientation;

4) he condemns dogmatism. Thus, he

has all the same positions as

Serbia. This certainly puts us close

to the Army.”23

The culminating

move of the SKS-JNA alliance against

Slovenia and in favour of a

recentralised Federation took place

at the 14th Extraordinary Congress

of the SKJ on 23 January 1990, when

the SKS attempted to outvote and

isolate the Slovene delegation and

browbeat it into accepting the SKS’s

policies, and therefore leadership,

within the Party. Milošević and

Jović relied upon the JNA to help

achieve this. They met at

Milošević’s residence on 10 January

along with Gračanin, Trifunović and

President of the Serbian Assembly

Zoran Sokolović to discuss their

strategy. Jović records their

conclusions as being that “The main

battle should be played out at the

14th Congress of the SKJ, to

preserve the integrity of the SKJ

and democratic centralism, at least

statutorily (formally). The goal is

to isolate the Slovenes, to keep

Croatia and Macedonia and possibly

Bosnia-Herzegovina as well from

joining them. JNA representatives

will be the standard bearers and we

will back them, so that we are not

leading the way, because that could

have a negative effect on the Croats

and Macedonians. The Army accepts

this sort of role.”24 The move against

the Slovenes at the 14th Congress

nevertheless failed to achieve its

desired ends, since the Slovenian

and Croatian delegations walked out,

marking the end of the SKJ’s

existence as a unified Party.

Serbia and the JNA turn against a

unified Yugoslavia

Following

Milošević’s defeat at the 14th

Congress, the policy of the SKS

shifted away from support for a

recentralised Yugoslav Federation

and toward, on the one hand,

acceptance of the SFRJ’s break-up,

and on the other, a Great Serbian

strategy. On 21 March 1990, Jović

suggested to Milošević that

‘Yugoslavia can do without Slovenia.

That will make it easier on us. We

will also have an easier time with

the Croats without them around.’

Jović noted that Milošević agreed

with him.25 In April-May 1990,

non-Communist nationalist parties,

which favoured independence for

their respective republics and with

which the Serbian regime was

unwilling to coexist, won elections

in both Slovenia and Croatia. Jović

writes that on 27 June 1990 he held

a discussion with Kadijević on how

to treat Slovenia and Croatia in the

new circumstances: Following

Milošević’s defeat at the 14th

Congress, the policy of the SKS

shifted away from support for a

recentralised Yugoslav Federation

and toward, on the one hand,

acceptance of the SFRJ’s break-up,

and on the other, a Great Serbian

strategy. On 21 March 1990, Jović

suggested to Milošević that

‘Yugoslavia can do without Slovenia.

That will make it easier on us. We

will also have an easier time with

the Croats without them around.’

Jović noted that Milošević agreed

with him.25 In April-May 1990,

non-Communist nationalist parties,

which favoured independence for

their respective republics and with

which the Serbian regime was

unwilling to coexist, won elections

in both Slovenia and Croatia. Jović

writes that on 27 June 1990 he held

a discussion with Kadijević on how

to treat Slovenia and Croatia in the

new circumstances:

“This situation with Croatia is a

reprise of what has already happened

and is still happening with

Slovenia. They want to preserve the

Yugoslav market but break up the

Yugoslav state. Given the course of

events, we conclude that we must

immediately formulate tactics for

further action. I tell Veljko

[Kadijević] that my preference would

be to expel them forcibly from

Yugoslavia, by simply drawing

borders and declaring that they have

brought this upon themselves through

their decisions, but I do not know

what we should do with the Serbs in

Croatia. I am not for the use of

force; rather, I should like to

present to them a fait accompli. We

should come up with a course of

action in this direction, with a

variant of holding a referendum

before the final expulsion, on the

basis of which it would be decided

where to place the borders. Veljko

agrees.”26

According to

Jović, Milošević expressed agreement

for this policy the following day,

28 June:

Conversation with Slobodan Milošević

on the situation in the country and

in Serbia. He agrees with the idea

of ‘expelling’ Slovenia and Croatia,

but he asks me whether the military

will carry out such an order ? I

tell him that it must carry out the

order and that I have no doubts

about that; instead, the problem is

what to do about the Serbs in

Croatia and how to ensure a majority

on the SFRY Presidency for such a

decision.

Sloba has two ideas: first, that the

‘amputation’ of Croatia be effected

in such a way that the Lika-Banija

and Kordun opstinas, which have

created their own community, remain

with us, whereby the people there

later declare in a referendum

whether they want to stay or go; and

second, that the members of the SFRY

Presidency from Slovenia and Croatia

be excluded from the voting on the

decision, because they do not

represent the part of Yugoslavia

that is adopting this decision. If

the Bosnian is in favour, then we

have a two-thirds majority. Sloba

urges that we adopt this decision no

later than one week hence if we want

to save the state. Without Croatia

and Slovenia, Yugoslavia will have

around 17 million inhabitants, and

that is enough for European

circumstances.27

Colonel-General

Konrad Kolšek, who at the time was

commander of the Zagreb-based 5th

Military Oblast, suggests in his

memoirs that the plan to ‘expel’

Slovenia and Croatia from Yugoslavia

can be dated to the previous summer:

‘The idea was probably actualised

already in August 1989 from Kupari,

where Milošević, Kadijević, Jović

and Trifunović gave themselves the

right, that in secret and on the

basis of political interests, divide

Yugoslavia. For that, they had

neither the constitutional nor the

moral right, nor authorisation from

the peoples of Yugoslavia. All that

which they did, they did secretly,

contrary to the law and the

Constitution and at their own

discretion.’28

Kadijević’s

support for this policy is confirmed

in his own memoirs, in which he

claims that the JNA’s strategy for

dealing with what he termed

“internal aggression” went through

successive phases.

“Phase 1 – up until the victory of

the right-wing

nationalist-separatist forces in the

multiparty elections in Slovenia and

Croatia [in the spring of 1990].

Those circumstances required a

concept of the use of the armed

forces on the basis of the task of

safeguarding the territorial

integrity of the country as a whole

and the creation of conditions for

its democratic transformation.

Phase 2 begins after the victory of

the national-secessionist forces in

Slovenia and Croatia and the

measures of the international

community that supported their

secession and exit from Yugoslavia.

With the start of this situation,

the tasks of the armed forces were

modified in the internal sphere in

the direction of creating the

conditions for the peaceful

resolution of the Yugoslav crisis,

including the peaceful exit from the

Yugoslav state of those Yugoslav

nations that so wished. [our

emphasis].”29

Kadijević writes

that the occasion of the change in

the JNA’s goals was in April 1990.

On 3 April, Kadijević as Federal

Defence Secretary proposed a series

of measures to restore the authority

of the Federal centre that Ante

Marković as Federal Prime Minister

rejected. “In my assessment that was

the last chance to attempt to

safeguard Yugoslavia in its exising

borders”, writes Kadijević; “When

that attempt failed then the Supreme

Command modified the tasks of the

JNA so that in the new conditions

they were: 1) to defend the right of

the nations that wished to live in

the common state of Yugolavia; 2) to

attempt to enable a peaceful divorce

with those Yugoslav nations that did

not wish to live any longer in

Yugoslavia.”30

The JNA becomes the ally of Serbia

and Montenegro

In order to carry

out its self-assumed policy of

“defending Yugoslavia” according to

its own preferred strategy, the JNA

command had to disregard Federal

institutions and constitutional

procedures that obstructed this

strategy, regardless of the legal

implications. According to

Kadijević, it was the JNA’s policy

“Acting through state institutions –

the Presidency of the SFRJ, the

Assembly of the SFRJ and the SIV –

not to allow the interference of

these institutions in the affairs of

the Army contrary to their

constitutionally and legally

confirmed authority.” Kadijević

claims that there were many such

attempts at interference,

“particularly on the part of the

SIV”.31 In Kadijević’s opinion,

Yugoslav Prime Minister Ante

Marković had an “anti-Serb stance”

and “destructive politics”.32 What

this meant in practice was that the

leadership of the JNA itself decided

how to ‘defend Yugoslavia’, and did

so in collaboration with those it

considered its allies (above, all

the leadership of Serbia), bypassing

or obstructing where necessary those

it considered its enemies. In order to carry

out its self-assumed policy of

“defending Yugoslavia” according to

its own preferred strategy, the JNA

command had to disregard Federal

institutions and constitutional

procedures that obstructed this

strategy, regardless of the legal

implications. According to

Kadijević, it was the JNA’s policy

“Acting through state institutions –

the Presidency of the SFRJ, the

Assembly of the SFRJ and the SIV –

not to allow the interference of

these institutions in the affairs of

the Army contrary to their

constitutionally and legally

confirmed authority.” Kadijević

claims that there were many such

attempts at interference,

“particularly on the part of the

SIV”.31 In Kadijević’s opinion,

Yugoslav Prime Minister Ante

Marković had an “anti-Serb stance”

and “destructive politics”.32 What

this meant in practice was that the

leadership of the JNA itself decided

how to ‘defend Yugoslavia’, and did

so in collaboration with those it

considered its allies (above, all

the leadership of Serbia), bypassing

or obstructing where necessary those

it considered its enemies.

Regarding the SFRJ

Presidency that comprised the JNA’s

formal Supreme Commander, Kadijević

claimed that it was comprised of

three categories of people: those

“solidly in favour of Yugoslavia”;

those who were “the fiercest enemies

of the unity of Yugoslavia”; and

those who were “vacillators who

fluctuated from situation to

situation” but were essentially

“unreliable in all critical

situations”.33 In this context

Kadijević chose to disregard his

constitutional obligation to obey

the SFRJ Presidency as a whole and

to work with its members

selectively, according to his own

political preferences:

“Those three categories of people

were supposed collectively to make

decisions, so that we were in a

situation of putting forward our

analyses and proposals also before

representatives of the enemy side.

Of course, we could not do this and

did not do this. But that made the

leading and command of the armed

forces more complex and made it

still more difficult and

complicated. Thus, for example, when

it was a question of planning and

issuing written Directives,

Decisions or Orders of the Supreme

Command, we were not able to

function in a way that more or less

all armies in the world normally

functioned, because every such

written document would immediately

have fallen into the hands of the

enemy. Therefore we were forced to

function in a completely different

manner.”34

This bias in

favour of some members of the

Supreme Command and against others

was expressed still more forcefully

by Adžić in memoirs published in

June 1992, when he stated that

“Treason existed, but in the

Presidency of the SFRJ – the

behaviour of Stipe Mesić, Janez

Drnovšek, Vasili Tupurkovski and

Bogić Bogičević. Those are pure and

orthodox traitors, foreign hirelings

and spies.”35 In other words, the

Chief of Staff of the JNA believed

all the non-Serbian and

non-Montenegrin members of his own

Supreme Command were the enemy. A

third high-ranking JNA officer to

bear witness to the “selective

loyalty” of the JNA top brass was

Major-General Aleksandar Vasiljević

who in the period 1991-92 served

successively as Deputy Chief and

Chief of the Security Administration

of the Federal Secretariat of

People’s Defence, better known as

the “Counter-Intelligence Service”

(KOS). In an interview published in

June 1992, Vasiljević recalls that

the JNA plan to overthrow the

governments of Slovenia and Croatia

in the spring of 1992 was not

revealed to all members of the

Supreme Command, since “At that time

the state leadership included some

people to whom such things could not

have been confided. I am not sure

whether the plan was discussed in

the state Presidency, but I believe

that Bora Jović was informed of

everything that was planned.”36

On 4 July 1990

Jović and Kadijević discussed the

possibility of the JNA “defending

the integrity of the country” with

or without Presidency approval.

According to Jović, Kadijević

informed him that:

“The military will do everything

possible to prevent unconstitutional

actions, to the greatest possible

legal extent, but if the Presidency

is unable to provide such a

decision, then other options must be

sought. We must come to an agreement

on this. They [the JNA] have worked

out a plan for Kosovo, Slovenia and

Croatia in this regard. A plan for

use of the military for the entire

country is also being drawn up and

will be ready in a few days,

although it will not be necessary in

the rest of the country, unless a

state of emergency is declared

throughout the country.

I ask him what these “other options”

are. He responds that if the

Presidency is unable to do its job

and adopt a decision on defending

the integrity of the country, the

military would carry out the order

of a group of members of the

Presidency, even though they do not

constitute a qualified majority."

[our emphasis]37

This passage

suggests that on this occasion

Kadijević took a major step toward

the transformation of the JNA from a

genuinely Yugoslav army under the

command of the 8-member collective

Federal Presidency, into one that

considered itself under the command

“of a group of members of the

Presidency”, i.e. its Serbian and

Montenegrin members. This did not

yet mean that the JNA had definitely

decided on a Great Serbian

orientation, but it did mean that it

had come to see itself as a

political ally of the Serbian

leadership, treating the non-Serbian

and non-Montenegrin republican

leaderships as its enemies. The

hostility of the JNA leadership in

particular to the Slovenian and

Croatian leaderships was the polar

opposite of its close friendship

with the Serbian leadership, with

which it coordinated its actions.

On 19 July 1990,

Jović records that Lieutenant

Colonel General Vujasinović, head of

the Military Office of the SFRJ

Presidency, asked him how to respond

to the request of Stipe Mesić,

Croatia’s member of the SFRJ

Presidency, to see the plans for the

JNA’s annual military exercises.

Vujasinović told Jović that he

suspected that Mesić intended to

show the plans to Tuđman. Jović

writes that “I tell him

[Vujasinović] that he [Mesić] can

request them in writing. Tell him

that you can give them to him only

on the basis of a decision by the

Presidency.” At the meeting of the

Presidency that day both Mesić and

Janez Drnovšek, the Slovenian

member, requested to see the plans.

Jović records that “We coldly agree

that they can be obtained from the

General Staff. I then ordered Gen.

Vujasinović to take the plans from

the General Staff to his office and

to inform them individually that

they can take a look at the plans in

his presence, but that they cannot

make any notes or copies.”38 The

passage indicates that high-ranking

JNA officers followed the orders of

Jović, as Serbia’s member of the

SFRJ Presidency, disregarding the

orders of the Croatian and Slovenian

members. On 19 July 1990,

Jović records that Lieutenant

Colonel General Vujasinović, head of

the Military Office of the SFRJ

Presidency, asked him how to respond

to the request of Stipe Mesić,

Croatia’s member of the SFRJ

Presidency, to see the plans for the

JNA’s annual military exercises.

Vujasinović told Jović that he

suspected that Mesić intended to

show the plans to Tuđman. Jović

writes that “I tell him

[Vujasinović] that he [Mesić] can

request them in writing. Tell him

that you can give them to him only

on the basis of a decision by the

Presidency.” At the meeting of the

Presidency that day both Mesić and

Janez Drnovšek, the Slovenian

member, requested to see the plans.

Jović records that “We coldly agree

that they can be obtained from the

General Staff. I then ordered Gen.

Vujasinović to take the plans from

the General Staff to his office and

to inform them individually that

they can take a look at the plans in

his presence, but that they cannot

make any notes or copies.”38 The

passage indicates that high-ranking

JNA officers followed the orders of

Jović, as Serbia’s member of the

SFRJ Presidency, disregarding the

orders of the Croatian and Slovenian

members.

Following the

transformation of the SKS into the

SPS in June-July 1990, the SKJ

organisation in the JNA reconsituted

itself on 19 November as a separate

political party in its own right,

the ‘League of Communists - Movement

for Yugoslavia’ (SK-PJ), which

claimed to be the SKS’s successor.

Its founding congress, at the Sava

Centre in Belgrade, was attended,

among others, by Kadijević, Adžić,

Mamula, Ljubičić, Gračanin, Deputy

Federal Secretary for People’s

Defence Stane Brovet and Milošević’s

wife Mirjana Marković. According to

its founding proclamation, the SK-PJ

‘supports all parties, movements and

individuals which are oriented

towards Yugoslavia, socialism and

brotherhood and unity among the

Yugoslav nations’.39 At its first

conference on 24 December, the SK-PJ

elected an eight-member Executive

Committee, including several current

and serving JNA officers and

admirals, one of whom was Mamula,

and Mira Marković.40 The SK-PJ

provided an additional institutional

basis for the collaboration between

the leadership of Serbia and the

JNA.

On 25 February

1991, Kadijević presented to Jović

his plan for a resolution of the

crisis. Kadijević believed that

“Serbia, Montenegro, the Army and

the Serb parties in Bosnia and

Herzegovina and Croatia are for

Yugoslavia; Slovenia and Croatia are

against Yugoslavia; Macedonia and

Bosnia-Herzegovina are wavering,

politically they are more inclined

toward the Slovene and Croatian

plan, but that does not guarantee

their survival and future.”41

Consequently, according to Jović:

“The military’s basic idea consists

of relying firmly on the forces that

are for Yugoslavia in all parts of

the country and through combined

political military measures

overthrowing the government first in

Croatia and then in Slovenia. For

these activities, we must take

advantage of the sphere of defence

where they have committed serious

criminal acts. In the wavering

republics (Macedonia and Bosnia and

Herzegovina) we must use combined

political measures – demonstrations

and revolts – to overturn the

leadership or to turn them around in

the right direction. These

activities would presumably be

combined with certain military

activities. This entire campaign

should be led by those members of

the SFRJ Presidency who have opted

for this course, with backing from

the military. All federal

institutions that accept this course

will be included in the campaign,

while the others will be removed

from power... Mass rallies should be

organised in Croatia against the

HDZ, Bosnia-Herzegovina should be

mobilised “for Yugoslavia”, and in

Macedonia the planned rally to

overthrow the pro-Bulgarian

leadership should be staged. There

should be mass rallies of support in

Serbia and Montenegro. Gatherings in

Kosovo should be banned.”42

This passage shows

that the JNA considered only those

SFRJ Presidency members that

supported its course (i.e. those

from Serbia and Montenegro) as its

legitimate commander, while its

support for Federal institutions was

conditional upon their acceptance of

its programme for Yugoslavia. The

Serbian leadership was able to rely

upon this bias in order to use the

JNA against its enemies. Thus when

Jović on 28 February presented the

JNA plan to Milošević, the latter

stated that the Serbian and

Montenegrin members of the SFRJ

Presidency should assume the role of

the JNA’s supreme commander

regardless of whether they had a

majority in the Presidency or not:

“Asked what we should do if we do

not achieve an adequate majority on

the Presidency for the necessary

decisions, he [Milošević] thinks

that we should adopt a decision with

those members who are “for” and that

the military should “obey”. He finds

it logical that we “get rid” of

anyone who opposes such action by

the Presidency.”43

Kadijević appears

to have been the individual within

the JNA most responsible for its

transition from a Yugoslav to a

Great Serbian army. According to

Dizdarević, “It is indisputable –

and this should be emphasised once

more – that Veljko Kadijević played

the key role in the betrayal of the

Army and its placement in the

service of the armed realisation of

the Great Serbian pretensions.”44 His

craven loyalty to the Serbian

leadership was not necessarily

representative of the JNA officer

corps as a whole. According to

Dizdarević there were many among the

JNA top brass who were dissatisfied

with Kadijević’s acquiescence in

Milošević’s Serbian-nationalist

course – he refers in particular to

Admiral Petar Simić and General

Simeon Bunčić.45 Mamula claims that in

1987 he viewed the danger that

Milošević posed to the stability of

Yugoslavia as being equal to that

posed by the Slovenian leadership.

He claims further that opposition to

Milošević among the higher ranks of

the JNA was greater than among the

republican leaderships; he refers in

particular to General Jovičić,

President of the SKJ organisation

within the JNA, and to General M.

Đorđević.46 Kadijević appears

to have been the individual within

the JNA most responsible for its

transition from a Yugoslav to a

Great Serbian army. According to

Dizdarević, “It is indisputable –

and this should be emphasised once

more – that Veljko Kadijević played

the key role in the betrayal of the

Army and its placement in the

service of the armed realisation of

the Great Serbian pretensions.”44 His

craven loyalty to the Serbian

leadership was not necessarily

representative of the JNA officer

corps as a whole. According to

Dizdarević there were many among the

JNA top brass who were dissatisfied

with Kadijević’s acquiescence in

Milošević’s Serbian-nationalist

course – he refers in particular to

Admiral Petar Simić and General

Simeon Bunčić.45 Mamula claims that in

1987 he viewed the danger that

Milošević posed to the stability of

Yugoslavia as being equal to that

posed by the Slovenian leadership.

He claims further that opposition to

Milošević among the higher ranks of

the JNA was greater than among the

republican leaderships; he refers in

particular to General Jovičić,

President of the SKJ organisation

within the JNA, and to General M.

Đorđević.46

The identification

of individuals within the JNA

command with Milošević’s programme

was therefore not automatic. In his

memoirs, Mamula claimed that in 1988

he lectured Kadijević – his

successor as SFRJ Minister of

People’s Defence - on the necessity

that “the JNA maintain its

all-Yugoslav standing and prestige.

Whoever attempts to dispute this –

Serbia, Slovenia or some third party

must know in advance that it will

not pass… To accept an asymmetry

toward certain republics and nations

would mean accepting the destruction

of the country.” However, Mamula

recalls that “I felt that the worms

of doubt were preying on Kadijević.”47

The latter was, Mamula suggests, on

the one hand ambitious and

self-willed and on the other hand

lacked the confidence to assume

complete responsibility for radical

action on the part of the JNA.48 The

implication is that Kadijević was

prepared to take unconstitutional

action on behalf of the JNA but was

afraid to do so alone, thus falling

in behind Milošević and Jović in

order to share the responsibility.

Mamula recalls:

“Damjanović [Colonel Milan

Damjanović, Chief of Security in the

Cabinet of the Minister] requested

at the end of 1988 that I receive

him. We met, and he conveyed to me

his observations from his holiday in

Kupari on the extremely close

relations between Milošević and

Kadijević. He knew my opinion on

Milošević and his circle and wanted

to report to me that Kadijević was

changing his position. When I once

again spoke with Damjanović some

time at the end of 1989 he assured

me that that year during their joint

holiday in Kupari Kadijević and

Milošević agreed on the political

and military engagement of the JNA

for the resolution of the Yugoslav

crisis. He proposed to me that I

engage myself decisively. He was

certain that I could do that and

that the majority of generals and

officers would support me.

Regardless of the possible

intentions of the security service

and Damjanović personally, his

currying of favour and expectations,

it is beyond doubt that Kadijević

had gone over to Milošević and that

the JNA was entering the dangerous

waters of a uninational, Great

Serbian orientation. Nothing worse

could have happened to the JNA and

Yugoslavia. In this way was

determined everything else that

happened in the succeeding years.”49

In Mamula’s

opinion, Kadijević declaration for

Milošević amounted to a betrayal of

the JNA:

“The JNA was not supposed either to

retain or expel anybody from

Yugoslavia. Its constitutional role

was extremely clear – to defend the

territorial integrity and

constitutional order of the country

until the Yugoslav nations agree

otherwise. There could be no

question of allowing Milošević or

anybody else to tailor Yugoslavia

with the assistance of the JNA and

establish a new state construction

in order that all Serbs live in a

single state. Yet that was precisely

the policy that was adopted.”50

The reason why

Kadijević “abandoned the Yugoslav

option and accept the Great Serbian”

Mamula explains as follows:

“But since the unsure and afraid as

a rule seek to hide behind the skirt

of the stronger, and Milošević and

the awakened Serb nationalism

appeared to be stronger, so

Kadijević decided. By all

assessments this occurred in 1989.

All the later resistance of General

Kadijević and General Adžić in

particular, of which Jović writes

exhaustively, was only the Way of

the Cross up Calvary to the

crucifixion.”51

Reasons of

neo-Communist solidarity, ethnic

bias and spinelessness aside,

Kadijević had two further reasons

for favouring Serbia. The first was

that the Serbian leadership, unlike

its Croatian and in particular

Slovenian counterparts, expressed

full support for and goodwill

regarding the JNA; it did not treat

the JNA as an occupying army or

threaten its economic or political

privileges. The second reason was

that the Serbian leadership remained

formally committed to the survival

of a Yugoslav state, even if this

“Yugoslavia” was in practice to

consist solely of Serbian and

Montenegrin lands. As Vasiljević

recalls, "the option for which the

leadership of Serbia declared was a

Yugoslav state. This attracted the

Army like a magnet to Serbia.”52

The SKS and JNA as uncertain allies,

April 1990 – March 1991

Jović’s diary

suggests that at least until March

1991, he and Milošević were prepared

to go along with JNA plans to impose

military rule in Slovenia and

Croatia so as to preserve the unity

of the country by force. On 23 March

1990 Milošević as President of

Serbia and Kadijević as Federal

Secretary for Defence held official

talks at which they publicly

affirmed a shared policy regarding

recentralisation of the Yugoslav

Federation, action against “Albanian

separatism” in Kosovo and “support

for the development of the Yugoslav

People’s Army as the united, joint

armed forces of all the nations and

nationalities, working people and

citizens of the SFRJ.”53 On 26 April

Jović and Kadijević met in private

and agreed on the need for the SFRJ

Presidency to adopt a resolution “to

force observance of the SFRJ

Constitution and federal laws

throughout the country, including

Slovenia and Croatia, by all means

possible, including political ones,

but by force if necessary.” Jović

writes that “As far as the break-up

of Yugoslavia is concerned, I

propose to him [Kadijević] that we

propose the emergency adoption of

laws on the procedure for seceding

from Yugoslavia, because that is

absolutely essential if we want to

avoid civil war. He agrees.”54 This

may have represented a genuine

readiness on the part of the Serbian

political leadership to accept a

unified Yugoslavia under military

rule as an acceptable alternative to

a Great Serbia, but more likely it

was a mere tactical means of

ensuring JNA action against Croatia

as a prelude to direct moves to

establish a Great Serbia. Jović’s diary

suggests that at least until March

1991, he and Milošević were prepared

to go along with JNA plans to impose

military rule in Slovenia and

Croatia so as to preserve the unity

of the country by force. On 23 March

1990 Milošević as President of

Serbia and Kadijević as Federal

Secretary for Defence held official

talks at which they publicly

affirmed a shared policy regarding

recentralisation of the Yugoslav

Federation, action against “Albanian

separatism” in Kosovo and “support

for the development of the Yugoslav

People’s Army as the united, joint

armed forces of all the nations and

nationalities, working people and

citizens of the SFRJ.”53 On 26 April

Jović and Kadijević met in private

and agreed on the need for the SFRJ

Presidency to adopt a resolution “to

force observance of the SFRJ

Constitution and federal laws

throughout the country, including

Slovenia and Croatia, by all means

possible, including political ones,

but by force if necessary.” Jović

writes that “As far as the break-up

of Yugoslavia is concerned, I

propose to him [Kadijević] that we

propose the emergency adoption of

laws on the procedure for seceding

from Yugoslavia, because that is

absolutely essential if we want to

avoid civil war. He agrees.”54 This

may have represented a genuine

readiness on the part of the Serbian

political leadership to accept a

unified Yugoslavia under military

rule as an acceptable alternative to

a Great Serbia, but more likely it

was a mere tactical means of

ensuring JNA action against Croatia

as a prelude to direct moves to

establish a Great Serbia.

The first joint

Serbian-JNA military action outside

of Serbia took place on 17 May 1990,

when Jović writes that “We take

measures to ensure that weapons are

taken from civilian TO depots in

Slovenia and Croatia and transferred

to military depots. We will not

permit TO weapons to be misused in

any conflicts or for forcible

secession. Practically speaking, we

have disarmed them. Formally, this

was done by the head of the General

Staff, but it was actually under our

order. Extreme reaction by the

Slovenes and Croatians, but they

have no recourse.”55 This move was

unconstitutional and was carried out

by the Serbian and JNA leaderships

working actively to undermine the

1974 SFRJ Constitution which, in

their opinion, was responsible for

the current crisis. According to

Kadijević “One of the most

significant measures of paralysing

the pernicious constitutional

concept of the armed forces was the

decision on confiscating the arms of

the Territorial Defence and their

placement under JNA control. Many

rose up against this decision,

particularly the Slovenes.”

[Kadijević’s emphasis]56

It appears that

the disarming of the TO in Slovenia

and Croatia formed part of the

preparations for the JNA’s planned

attack on both republics. According

to Kadijević:

“To paralyse the Territorial Defence

to the maximum extent in those parts

of the country where it could be

used as a base for the establishment

of the armies of the secessionist

republics or secessionist forces.

With this goal in mind the entire

Territorial Defence was disarmed

prior to the start of the armed

conflict in Yugoslavia. Besides

this, through part of the officer

corps of the Territorial Defence we

endeavoured to keep it to a maximum

extent outside the control of the

secessionist political leaderships.

We partly succeeded in this,

everywhere more than in Slovenia. Of

course, we used the Territorial

Defence of the Serb parts in Croatia

and Bosnia-Herzegovina in actions

together with the JNA.” [our

emphasis]57

The disarmament of

Slovenia and Croatia could have

served as a prelude either to

military rule in both republics or

to the forcible withdrawing of

borders on a Great Serbian basis.

Although the Serbian leadership had

definitely decided on the latter,

the JNA leadership continued to

hedge its bets, discussing with its

Serbian counterpart both

possibilities. Nevertheless, the two

allies proceeded to coordinate

action against their common enemies.

On 3 August Kadijević reported to

Jović on the JNA’s plans vis-à-vis

Slovenia. Three days later Kadijević

and Jović met again to discuss the

JNA proposals to be put before the

SFRJ Presidency.58 On 10 August Jović,

Kadijević, Milošević, Trifunović and

their families spent a day on an

excursion to the Adriatic island of

Mljet. They agreed regarding SFRJ

Prime Minister Ante Marković, to

whom Kadijević as Defence Secretary

was formally subordinate, that “We

definitely have to get rid of him.”59

The JNA was

suspicious of the anti-Communist

Serb rebels in Croatia under the

leadership of the Serbian Democratic

Party (SDS). Nevertheless its

hostility to the Croatian

authorities and their efforts at

self-armament as well as its

friendship with the Serbian

leadership ensured that whatever its

intentions, in practise it came down

on the side of the SDS against the

Croatian leadership. On 17 August

JNA jets, sent on the order of Adžić

as Chief of Staff, intercepted three

helicopters of the Ministry of

Internal Affairs (MUP) of the

Republic of Croatia that were

attempting to intervene against the

Serb rebels at Knin. On the same day

JNA troops were sent on to the

streets of Knin to defend the town

against advancing Croatian MUP

forces.60 Vuk Obradović, official

press spokesman of the Federal

Secretariat for People’s Defence

(SSNO) and then or subsequently a

key SPS supporter in the JNA, issued

a statement denying that JNA jets

had intercepted Croatian MUP

helicopters and claiming that “the

Army unswervingly follows the policy

of brotherhood and unity and its

function and responsibility

determined by the SFRJ

Constitution.”61 The JNA claimed to be

preventing violence between Croatian

and rebel-Serb forces; in practice

it acted as a military umbrella for

the latter. By February 1991, at the

latest, the JNA commanders were

fully behind the Serbian

leadership’s defence of the Serb

rebels in Croatia. According to

Jović, Kadijević argued during their

meeting of 25 February 1991 that “In

Croatia, the Serbian Krajina should

be strengthened institutionally and

politically and its secession from

Croatia should be supported (not

publicly, but in de facto terms).”62

Kadijević therefore viewed the SDS’s

Krajina parastate as an integral

part of his strategy against

Croatia.

In the crisis

occasioned by the efforts of the

Croatian leadership to create

independent armed forces for the

republic the Serbian leadership and

JNA collaborated in a manner that

overrode other state organs at the

Federal level. On 23 November 1990,

Kadijević consulted with Jović over

the planned arrest of General

Špegelj, Croatian Minister of

Defence, asking him whether the

Croatian government and Yugoslav

Prime Minister Ante Marković should

be informed beforehand. They agreed

to inform the Croatian government,

but not Marković.63 Kadijević

therefore chose to act in secret

from the head of the government of

which he was a member. On 15 January

1991 Jović and Kadijević discussed

military measures to be taken

against Croatian forces: In the crisis

occasioned by the efforts of the

Croatian leadership to create

independent armed forces for the

republic the Serbian leadership and

JNA collaborated in a manner that

overrode other state organs at the

Federal level. On 23 November 1990,

Kadijević consulted with Jović over

the planned arrest of General

Špegelj, Croatian Minister of

Defence, asking him whether the

Croatian government and Yugoslav

Prime Minister Ante Marković should

be informed beforehand. They agreed

to inform the Croatian government,

but not Marković.63 Kadijević

therefore chose to act in secret

from the head of the government of

which he was a member. On 15 January

1991 Jović and Kadijević discussed

military measures to be taken

against Croatian forces:

“The Serbs in Croatia are

surrendering their weapons, the

Croats are not. They must be taken

by force, by applying the law. We

are considering all circumstances

and variants. Every one of them

leads to resistance and bloodshed.

If they offer resistance, then we

must crush them.”64

On account of

Kadijević’s loyal support Jović felt

completely confident in his ability

to threaten his Croatian opponents

with the JNA. On 18 January 1991

Jović brokered an agreement with

Stipe Mesić, Croatia’s

representative on the Yugoslav

Presidency, for the peaceful

surrender of Croatian weapons to the

JNA. Jović threatened Mesić in the

name of the JNA:

“I try to convince him that they are

working against their own interest

by deciding not to surrender the

weapons, because the military will

take them by force. I explain to him

the procedure for putting

individuals on trial, which will

eventually indicate the

responsibility of the top

leadership. If they resist, then we

will crush them by force.”65

Neither partner in

the alliance, however, favoured a

peaceful resolution of the crisis;

both sought an armed showdown with

Croatia. Although Mesić did agree

that Croatia would surrender 20,000

submachine guns, the agreement was

opposed by Milosević and the JNA.

Jović writes:

“I inform Slobodan of the agreement

by telephone. He blows his top. He

says all sorts of things: We will be

cheating our people, this will be

deception, betrayal, all sorts of

things. As if he would rather have

us take the weapons by force that

have them surrendered voluntarily. I

ask him directly: Does he want

bloodshed over a matter that we

might be able to resolve peacefully

? In his opinion this is not a

solution. The guilty parties must be

punished.”66

Jović records the

following day that the JNA agreed

with Milošević on this question:

“I speak with Veljko and Adžić at

the SSNO. They are preoccupied by

the same issues as Slobodan. The

army must not lose esteem among the

people. They are not satisfied with

taking control of 20,000 submachine

guns.”67

That day Kadijević

and Adžić showed Jović the film they

had made documenting the Croatian

armaments programme. The three of

them then “reached an agreement” on

action against the Croats in which

they rejected the idea of a “violent

overthrow of the authorities” in

favour of “the variant of thwarting,

weakening and compromising the

current HDZ [Croatian Democratic

Community] authorities”. Even if the

Croats were to agree to surrender

the weapons, “we will apply a

special variant of exposing the HDZ

policy, weakening their authorities

and thwarting their tactics. As part

of that, everything necessary will

be done to discredit the Croatian

authorities as a result of the

illegal arms build-up and their

anti-Yugoslav policy.”

This amounted to

political collaboration at the

expense of the legal and legitimate

authorities of a constituent

republic of the SFRJ. Furthermore,

the fact that the agreement aimed at

“weakening and compromising” the

Croatian authorities rather than

overthrowing them outright suggests

that the policy favoured by the

Serbian leadership had gained the

upper hand over that of the JNA,

since Milošević and Jović needed the

HDZ regime in place in Zagreb if

they were to engineer the

dismemberment and expulsion of

Croatia from the Federation. By

contrast, the overthrow of the HDZ

regime would have pre-empted the

possibility of establishing a Great

Serbia.

On 25 January

Kadijević, at Jović’s request,

presented before the SFRJ Presidency

a proposal to authorise the JNA to

disarm Croatian armed formations. At

the same time the JNA was placed on

high alert. Nevertheless the

Presidency rejected Kadijević’s

proposal by three votes to four,

with Drnovšek, Mesić and Bogičević

voting against, denying the Serbian

and Montenegrin members the overall

majority of five votes that they

needed. Following the setback

Belgrade TV broadcast the film made

by the KOS showing Croatian Defence

Minister Špegelj describing his

preparations for war with the JNA.

Milošević, as the President of

Serbia in de facto control of

Belgrade TV, had broadcast the film

at the precise moment of the

Presidency meeting to strengthen

Kadijević’s hand. Nevertheless

Kadijević’s proposal still failed to

receive a majority of Presidency

votes.68

Jović and

Milošević however remained confident

that they could use the JNA to

accomplish their goals. According to

Jović, Milošević told him on 26

January that ‘once the military

“covers” Serb territory in Croatia

we no longer have any reason to fear

the final outcome of the Yugoslav

crisis.’69 Jović himself believed

that:

“The best thing right now would be

for us to use the strength that we

have at our disposal (the army) and

the democracy that we want to impose

(an expression of popular will) to

ensure both a peaceful way out of

the crisis and a favourable solution

for the Serb nation, as well as for

all others if that is possible. Let

the Croatians impose their war if

that is what they want, and it

appears that it is. We will then

have to defend ourselves, we will

have to defend the Serb nation,

which does not want to leave

Yugoslavia by force.”70

In this period the

ideological affinity between the

allies was readily paraded. On 21

December 1990 the SFRJ Presidency

led by Jović as President received a

delegation of the armed forces of

the SFRJ led by Kadijević, in

connection with 22 December – the

Day of the JNA. On this occasion,

Jović praised the JNA and its

defence of Yugoslavia and warned

that “the SFRJ Presidency will not

tolerate the Federation’s

constitutional competencies and

those of its organs in the realm of

People’s Defence and the armed

forces being infringed upon. It will

resolutely defend the unity of the

armed forces and its system of

management and command. It will not

tolerate any formation of parallel

armed forces because this directly

threatens the SFRJ’s constitutional

order and integrity.” Kadijević

responded by thanking the Presidency

for the greeting received and

promising that “The members of the

army are firmly committed to a

united Yugoslavia as the shared

democratic homeland of its citizens

and equal nations and nationalities.

The JNA is exercising its social

role successfully as it is capable

of carrying out tasks stemming from

its function endorsed by the SFRJ

Constitution.”71

The strength of

this alliance was indicated in two

separate incidents in early March

1991. Milorad Vučelić, one of

Milošević’s key propagandists, wrote

publicly at this time that “it would

be best” if “the forces of the

Yugoslav Peoples Army occupied the

ethnic space of the threatened Serb

nation, or to be more precise

positioned itself on the borders of

the current Serb autonomous oblast

of Krajina and guaranteed all human

and civic rights to the Serb nation

and the citizens that live on this

territory.”72 On 6 March, two days

before Vučelić’s article appeared in

print, Jović commanded the JNA to

intervene in Croatia in defence of

the Serb rebels: The strength of

this alliance was indicated in two

separate incidents in early March

1991. Milorad Vučelić, one of

Milošević’s key propagandists, wrote

publicly at this time that “it would

be best” if “the forces of the

Yugoslav Peoples Army occupied the

ethnic space of the threatened Serb

nation, or to be more precise

positioned itself on the borders of

the current Serb autonomous oblast

of Krajina and guaranteed all human

and civic rights to the Serb nation

and the citizens that live on this

territory.”72 On 6 March, two days

before Vučelić’s article appeared in

print, Jović commanded the JNA to

intervene in Croatia in defence of

the Serb rebels:

“Lately we have been too occupied

with Pakrac and other events in

Croatia. I ordered the use of force

without convening the Presidency,

because it was Sunday. The members

of the Presidency were not in

Belgrade. Janez and Vasil grumbled a

little, but the decision was

nevertheless affirmed.”73

The Serbian

leadership was able to rely on the

JNA against its Serbian domestic

opponents as easily as against the

Croats and on 9 March Jović ordered

JNA intervention to crush opposition

demonstrations in Belgrade: “I

consult with the members of the

Presidency whom I can reach by phone

(everyone except Mesić and

Drnovšek). I order Veljko to send

the military out into the streets

and occupy the space in front of all

threatened state institutions.”74

Strains in the SKS-JNA alliance,

April 1990 – March 1991

The differences in

the positions of the SKS and JNA

leaderships nevertheless made for a

difference in outlook. The politics

of the SKS under Milošević were

based on the perception that

Serbia’s rights were being violated

by an “anti-Serbian coalition” of

Slovenes, Croats, Kosovo Albanians,

Bosnian Muslims and Macedonians that

determined Yugoslav policy at the

Federal level. Milošević’s policy

therefore involved asserting

Serbia’s rights, as he saw them,

against the rest of Yugoslavia. By

contrast, Kadijević and other senior

figures in the JNA sought to

strengthen the powers of the Federal

organs (above all of the JNA itself)

at the expense of the powers of the

republics. Already in 1989 there

were signs that, despite their

alliance, the views of the SKS and

JNA leaderships did not wholly

converge. On 19 September 1989,

Jović and Kadijević conferred and

agreed that the JNA had a

constitutional obligation to protect

the SFRJ Constitution but could do

so only through the SFRJ Presidency

as its Supreme Commander.75 Jović and

Milošević rapidly became

dissatisfied with what they

perceived as Kadijević’s failure to

adopt more resolute measures against

the Slovenes and his reliance upon

constitutional-legal mechanisms to

halt their push for sovereignty: “We

believe the Slovenes will not

listen. We feel that this is the

beginning of the end of Yugoslavia.”76

The radical steps

that the Serbian leadership took to

cut the Gordian knot of internal

SFRJ relations and reorder them

according to Serbian state interests

were not necessarily easy for the

JNA top brass to swallow, committed

as it was to the existing order of a

unified Yugoslavia under a Communist

government. On 7 June 1990, Jović

writes that “Veljko Kadijević is

worried and despairing over the

decision by the Serbian leadership

to form a Socialist Party. He feels

that this represents the definitive

disintegration of Yugoslavia, that

the Americans have achieved their

goal in Serbia as well, that they

have removed the SKJ from the

historical scene.”77 In Jović’s view

Kadijević’s politics were weak,

anachronistic and blind toward the

need for change. Following his

conversation with Kadijević on 4

July 1990, Jović notes that “Veljko

does not even mention our agreement

on the 27th of this month [i.e. 27

June] to expel Slovenia and Croatia

from Yugoslavia”,78 suggesting that he

(Jović) doubted Kadijević’s

commitment to this project. On 13

July 1990 Jović writes that “Veljko

Kadijević reports to me on new

aspects in the development of the

situation and on military

preparations. I am beginning to

doubt the value of all these reports

of his when he does not demonstrate

any real determination to do

anything radical to interrupt the

negative trends.”79 The passage

indicates both Kadijević’s view of

the Serbian member of the Yugoslav

Presidency as an authority to which

he had to report, and the latter’s

lack of confidence in Kadijević.

Kadijević at the same time disagreed

with Jović over the question of

arming the Serb population of

Croatia. Jović writes that “The

Serbs in Croatia have begun to

organise into partisan detachments.

For now, that knowledge is based on

statements by individuals. The Serbs

in Serb municipalities have asked

that TO weapons be turned over to

them. I tell Veljko that that should

have been done, but he does not

agree.”80

Despite his

apparent acquiescence in Jović’s

plan to expel Slovenia and Croatia

from Yugoslavia, during the first

months of 1991 Kadijević’s preferred

goal was the military overthrow of

the governments of both republics in

order to retain them forcibly within

Yugoslavia. By contrast, Jović and

Milošević were never enthusiastic

about this strategy, both because

they doubted the resolution of the

JNA and, it would seem, because they

needed Tuđman and the HDZ in power

in Croatia to act as their partners

in the redistribution of Croatian

and Bosnian territory, as well as to

provide the “Ustasha” bogeyman that

would justify a campaign to “defend”

the Serbs outside Serbia.

Nevertheless, the plans of both the

Serbian leadership and of the JNA

required the disarmament of Croatian