|

Case

study 2

In a passageway in

the centre of Ljubljana, for 25

years now there has been a graffiti

depicting a sinking ship named

Yugoslavia. During that time, many

other new graffiti and tags have

been added around it, but the image

has in essence remained intact. I

view it as a symptom of the

ambivalent, even polyvalent

relationship of Slovenians towards

their Yugoslav and socialist past.

In this study, my

starting point is this very feature

of contemporary urban culture, one

of the hundreds that I have

photographed during the last several

years or whose photos I have

received from other “graffiti

hunters”. As Barthes (1992, 15)

says, each photograph brings about

“something threatening”, it “brings

back death”. Among the heap of

graffiti and street art that I have

photographed or obtained by other

means, I am interested in this

research in the opposite: “bringing

back life” – the motive therein, the

existence of “Yugoslavia after

Yugoslavia”. In short: I was

fascinated by a picture of it in a

field quite neglected by research –

the contemporary subculture of

graffiti and street art. In other

words, I wondered what its

relationship to the former common

state, its socialism, anti-fascist

struggle, its leadership, and its

ideology was: both in a positive,

affirmative sense, and in a

negative, hostile manner. The

central question of my research was

how contemporary authors of graffiti

and street artists (de)construct the

Yugoslav era; what kind of

pro-Yugoslav or anti-Yugoslav

graffiti and street art there is;

what antagonisms they reflect and

create at the same time. In short:

what the walls of the post-Yugoslav

homelands say about the homeland

that was former Yugoslavia. Or if we

were to use Foucault’s terminology:

What kind of political subjectivity

is created in this process? In this

regard, this analysis is

complementary with other analyses

dealing with the construction and

presentation of the Yugoslav era in

advertising, popular culture,

design, art, and last but not least,

political discourse.

I. Introduction and Definitions of

Political Graffiti and Street Art

The study is part

of my wider interest in researching

cultures of post-Yugoslav collective

memory, post-socialist ideologies

and urban subcultures; specifically,

the exact points in which they

overlap. I have been collecting

these materials by means of “

barefoot culturology” from the late

nineties onwards, particularly in

the northern parts of the former

federation (Slovenia, Croatia,

Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia). In

this period, I discovered more than

270 examples of graffiti and street

art, most of which I photographed,1

while also finding a smaller portion

in other sources (books, newspapers,

articles, and catalogues). I

followed the usual three-part

organisation of this kind of

fieldwork which was suggested, among

others, by Collieri (1996, 167-173):

preparatory observation, structured

research and final analysis.

I define graffiti

and street art as a form of specific

aesthetic expression in a public

space with a clear message: it is

temporary, it can be destroyed, it

is illegal (condemned as vandalism

in the eyes of dominant discourses

and institutions), it is critical of

the existing, it is represented by

an image or object and/or word, it

always interacts with its

environment (the graffiti’s “text”

must always be read together with

its physical and social “context”),

it is in constant interaction with

its environment (almost always

several at once), it shapes its

subculture (with its ethics,

unspoken rules, its stars,

innovators, epigones, imitators,

experts etc.) and its authors are in

most cases anonymous. Their

characteristics include

untranslatable plays on words and

motifs, humour, paradoxes, loanwords

and the use of paraphrase, rhymes,

aphorisms and witticisms. They are

created and collected primarily by

young people – a rather profiled

medium, generationally speaking.

Graffiti are intended to “entertain,

provoke and make us think” (Sterk

2004, 68); they are a “mode of

communication that is personal and

free from the usual social

limitations which, as a rule,

prohibit people from expressing the

richness of their thoughts” (Abel,

Buckley 1977, 3).

Graffiti are

two-dimensional wall paintings, and

their main types are the tag (logo

and signature of the graffiti’s

author), the piece (abbreviation of

masterpiece, a high-quality and

complex graffiti), the throw-up, or

bomb (a quickly made graffiti), the

roof-top (a graffiti on the upper

part of a building), the character

(a caricature from popular culture),

the wall of fame (walls where the

most elaborate graffiti of the wider

and local scene of the graffiti’s

author are located one next to the

other), and the mural (most often

legally-painted large-scale

illustrations on buildings). Street

art developed later, during the last

20-25 years, which is why it was

labelled as post-graffiti art, and

in most cases it is

three-dimensional (stencils,

stickers, public installations and

visual interventions, paste-up

posters, cuttings etc.). The next

important difference is aesthetic: I

classify graffiti into auratic

creations, it is a case of a “‘here’

and ‘now’ art piece”, which has “a

singular presence in the place where

it is located” (Benjamin, 1998, 150)

– they are in some way always

unique, unrepeatable. Stickers,

posters and stencils, however, are

in a way post-auratic: free from

originals and “rituals” (Ibid, 154,

155), they can be infinitely

technically reproduced, and can be

set up in a public space by

practically anyone. Furthermore: the

essential feature of graffiti and

street art is that they are an

illegal medium of social groups with

a communication deficit – used by

those who cannot otherwise express

themselves (see also: Chaffee 1993,

12, 16, 17).2 In this sense,

McLuhan's maxim that the medium is a

message is a viable reference here:

a graffiti, the very act of its

creation, is in itself a message,

regardless of the specific content,

since it publicly reveals something

that is not contained in other

media. Likewise, it is also

important which graffiti remain and

on the other hand which are erased,

removed and enhanced or have their

meaning replaced – how quickly this

is done, by whom and in what manner.

For this study, it

is important to distinguish between

so-called aesthetic or subcultural

graffiti and political graffiti. The

latter engage more directly in

social criticism, and in accordance

with that I treat them as a

significant political medium: in

addition to the usual

characteristics of the subculture

(specific aesthetic form, the

illegal aspect, etc.), they have a

clear political agenda. The contents

of political graffiti are

definitively superordinate to form:

aesthetically speaking, they are

poorly made most of the time, they

contain neither the standard finesse

of the genre nor insider secrecy,

their goal is political propaganda,

a call to action, mobilisation, and

they are a trigger for it (see:

Velikonja, 2008 and 2013). Crossing

(as well as crossing out, or

crossing over), i.e. drawing

graffiti over existing ones – which

is an exception in the unwritten

ethics of graffiti drawing – is a

rule here.3

II. The Method Question:

Semiology between Qualitative and

Quantitative Approaches

Graffiti and

street art, particularly those which

are politically-oriented, are almost

impossible to research from the

author's perspective, because

authors are as a rule anonymous or

difficult to track down – drawing

graffiti is still prohibited and

oppressed. Even when I was

completely certain of who the author

was – based on various information

and sources – the author himself did

not want to admit to it in

conversation. In certain cases, the

authors are explicitly known and

their graffiti signed: right-wing

fan groups (e.g. “Torcida”, “Viola”,

“Delije”), the extreme right-wing

(with the abbreviations of their

organisations, e.g. “Radikalna

Ljubljana”, or the “Autonomous

nationalists of Slovenia”), or the

clerical fascist groups (e.g.

“Serbian Action”, whose graffiti

also include its Internet address).

For this reason, I

explored graffiti at the image’s

very location, not in the place of

its origin, or in the place where it

is observed, i.e. where its effect

is produced.4 However, I must direct

attention to the significance of its

environment: to understand a

graffiti, it is not sufficient to

have a “good eye”, or to interpret

its composition or the power of the

image itself, but its location as

well. Contextual knowledge is

important: social and ideological

knowledge is perhaps even

superordinate to form in that

regard. In other words: a visual

analysis should be carried out

together with the non-visual

background that places the image

aesthetically and ideologically,

with all its completeness.

This is why

choosing semiology as the main

research method makes sense. It

explores images together with their

ideological environment – more

precisely, it explains how images

(de)legitimise the existing balance

of power. In other words: semiology

breaks down the ideological

justification of social structures,

i.e. the way in which certain groups

set up their own ruling position

based on their symbols and

narratives and based on which others

dispute it. This is expressed in

different fields, including the

field of political graffiti. During

the research – referring to the

classic works in the field of

semiology (Barthes 1990, 1992, 1993,

Eco 1998, Hall 2012, Guiraud, 1983)

– I used the semiological method in

two steps. In the first, I was

interested in how both pro-Yugoslav

and anti-Yugoslav ideologies were

constructed in graffiti and street

art. I followed the descriptions of

Yugoslavia, its socialism, its

leadership, anti-fascism, etc. –

simply put, the period between 1941

and 1991 in contemporary graffiti

and street art; in the same way, I

also followed descriptions of the

opposite, the anti-Yugoslav,

anti-socialist and anti-Partisan

ideologies. The third chapter,

therefore, encompasses the

“denotative level” (Barthes 1990,

200), the description, the "literal

meanings of symbols” (Hall, 2012,

405), the discursive construction of

the meaning of such graffiti and

their classification.5

In the second

step, in chapter Four, I delve into

the “connotative level” (Barthes,

1990, 200, 201): what the “higher”

meaning of graffiti and street art

is in the semiotic sense, how

“connotation 'trims' the denoted

message” (Barthes, 1990, 201; 1993,

Barthes, 1993, 111-117; see also:

Guiraud 1983, 33, 34). Hall (Ibid.)

claims that symbols “acquire their

full ideological value – and can

therefore act openly to articulation

with wider ideological discourses

and meanings – at the level of their

'associative' meanings (i.e. at the

connotative level)”. To use Eco's

analytical words (1998, 184), “a

message is received in a concrete

and fixed acceptance that qualifies

it”. I investigated how the

pro-Yugoslav and anti-Yugoslav

graffiti are involved in current

ideological and political conflicts

on the post-socialist and

post-Yugoslav mental map, thus

(also) how they criticise and

antagonise other ideological

discourses and practices. They are,

in fact, as a rule, translated into

the categories of the recent past

and its protagonists. In other

words: in this second step, I deal

with issues such as what kind of

“Manichean ideology”, what kind of

“fundamental opposition” (Eco, 1998,

148, 168, 169) is created by writing

graffiti like “OF” (Oslobodilacki

Front – Liberation Front), “Tito

lives”, “Long live 29 November”, or

spraying red stars and the like and

what all these really mean; and

also, what graffiti of opposing

contents mean today (“Tito is a

criminal”, “NDH” [abbreviation of

Nezavisna Država Hrvatska –

Independent State of Croatia],

“Death to communists”, etc.).

I thoroughly

reviewed the collected material on

multiple occasions, upon which I

refined and classified it. Before

the actual analysis, I would like to

explain some methodological

specifications of the study. First,

this will be done in regards to the

combination of qualitative and

quantitative research cases. The

semiotic approach is as a rule used

for the analysis of specific

examples in the studium and punctum

methods (culturally accepted, or

non-coded image parsing – Barthes,

1992, 27-29, 410-412); of a

dominantly hegemonious, conducive or

oppositionally and globally

contradicting position or code

(Hall, 2012, 410-412), or with a

“play of oppositions” and a “fixed

scheme”, that are constantly

repeated in certain cultural

artefacts (Eco, 1998, 160-162). I

selected the analytically connected

denotation-connotation pair in the

Barthesian sense which I combined

with the other, quantitative method.

The content analysis registers the

frequency with which the same motif

or image is repeated. In the

analysis I connected the two,

firstly by counting how often a

certain group of motifs reappears,

and subsequently exploring their

denotative (descriptive) and

connotative (meaning-centred)

dimensions. Second, the primary

visual structure of graffiti is

multimodal, composed of text

(specifically abbreviations of

different organisations and groups,

names of protagonists, political

salutes and brief calls), images

(political symbols, emblems,

historical specifications etc.) and

colour, whereby sometimes only the

first or only the second element

appears. It is, however, essential

to always analyse them as a unit.

Furthermore, the

fate of graffiti and street art is

such that they almost always

experience some kind of change: they

are crossed out, amended, painted

over in white, muddled or expanded

through text or images. Political

graffiti and street art are a kind

of wall feuilleton, a series: a

medium for the battle between

various graffiti artists,

documenting graffiti battles or

cross-out wars where one layer comes

right on top of the other, the

original message is destroyed,

restored, altered, destroyed again

and so on.6 In short, they are hardly

ever analysed in isolation. This is

also how I divided them: into those

that have, despite everything,

remained more individual, less

confronted and less antagonised

(groups 1 and 2) and those that were

completely antagonised (group 3).

Fourth: Some

graffiti isn’t necessarily connected

to the Yugoslav, socialist or

Partisan experience: the red star

wasn’t only a symbol of

Yugoslavianism, socialism or

Partisanism, i.e. of the period

between 1941 and 1991, much like

Nazi symbolism and imagery – whether

global (the swastika, Nazi salutes,

other Nazi symbols such as 18, 88,

the Totenkoph), or local (symbols of

the Ustashas, Chetniks, Home Guard)

– were not always the antithesis of

anti-Yugoslavianism. Both are also

more general symbols of left-wing

and right-wing sub-politics. The

vast majority of the analysed

graffiti truly refers to the

Partisan and Yugoslav era, while

some don’t as they are “timeless”

symbols of socialism or communism or

Nazi fascism. The same applies to

what they condemn: graffiti like

“Death to clero-fascism”, “Fuck

nations” and the like can refer to

current clero-fascists and Nazis or

to those of the past, in the same

way that “Socialism is a disease” or

“Death to communism” can refer to

socialism of the past or its

present-day “leftovers” (for

example, udbomafija – the State

Security Mafia – in Slovenia etc.).

I have taken into consideration only

those which in some way had a

connotation with the Yugoslav

socialist experience or which were

“translated” into it.

Fifth. Analyses of

this type treat that which was

immediately destroyed and that which

remains with equal importance.

Despite the fact that such urban

visual creations can be destroyed by

definition – the lifespan of

contemporary graffiti is several

months, rarely several years – in

traditionally antifascist areas

(Primorska, Istria, Kvarner in

Slovenia), post-war graffiti can be

spotted to this day, some of which

bare a clichéd witness to “Trst

Gorica Rijeka Istria” (Prestranek,

2015), while others are dedicated to

the Partisan army (Vela Luka, 2008).

“Long live Marshall Tito”, “We want

Yugoslavia” and “This is Yugoslavia”

(villages in the Gorizia Hills,

2013) can also be found. Despite

having faded, they can still be read

and understood. To this I can also

include the huge “stone graffiti”

visible from tens of kilometres

away, with slogans spanning across

dozens of metres of stone, placed in

honour of Tito and Yugoslavia during

the initial post-war decades and

remaining to this day (I found

several examples in Primorska,

Istria and central Bosnia). Two

graffiti dedicated to Stalin have

remained for decades, surviving even

the cruel confrontation with the

Inform Bureau: the first one

alongside the Tito graffiti in the

main street in Ljubljana, Dunajska

(Becka) Street, and the second one

in Kopar. This serves as further

proof of the fact that graffiti are

visible to all but noticed by few.

Sixth. It is

practically impossible to determine

the exact number of (political)

graffiti because they exist one day

and are gone or perhaps changed the

next. It is impossible to simply

“scan” a single let alone multiple

cities at the same time to obtain an

exact graffiti count. Be that as it

may, the quantitative aspect of the

analysis should not be disregarded,

as it is relevant from a research

standpoint as well. That is why I

didn’t treat the graffiti count I

included in the research as an

absolute value, but rather as a

share in relation to others.

Last but not

least, I analysed only some examples

of graffiti and street art products:

if the same graffiti, stencil,

poster or sticker appeared multiple

times, I counted them as one. This

skews or minimises their presence in

urban environments: for example,

stencils with Tito’s portrait and

the “Republic Day” slogan were

present on every corner in central

Ljubljana during the nineties –

which is why I only recorded two of

its variations (the red one and the

black one) in this study. The same

goes for the most common phrases and

symbols (“steel repertoire”, “SF-SN”

[abbreviation of Smrt Fašizmu,

Sloboda Narodu – Death to Fascism,

Freedom to the People], “Tito”, the

red star, the emblem of OF

[Oslobodilacki Front – Liberation

Front], the hammer and sickle etc.),

given that there are many variations

on the theme and that they are also

presented through different

techniques (graffiti, stencil,

sticker, etc.). That is why this

needed to be treated through

primarily qualitative means, not

just the quantitative method which

would only measure the frequency of

their occurrence.

III. Denotative Level –

Classification of Pro-Yugoslav and

Anti-Yugoslav Graffiti and Street

Art

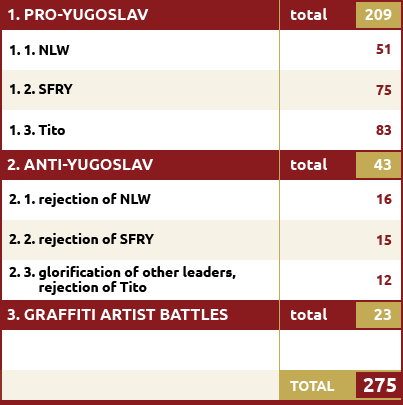

As Rose (2012,

108) says, semiology assumes that

“the constructions of cultural

differences are expressed through

the agency of signs on the image

itself”. Based on the thesis that

views photography as

“self-understood proof” (Rose, 2012,

300), i.e. “standardly precise

perception” (Collier and Collier,

1996, 7), I recorded groups of

repetitive signs and categorised

them. I further divided the

collected corpus of 275 photographs

of graffiti and street art into

three large sign categories

according to their themes (whereby

the first two were divided into

three smaller groups) which rather

precisely articulate the

pro-Yugoslav and anti-Yugoslav

ideologies. The first category,

comprised of 206 examples, includes

pro-Yugoslav symbols, divided into

those with Partisan and NLW –

National Liberation War (1. 1), SFRY

– Socialist Federal Republic of

Yugoslavia (1. 2), and Tito (1. 3)

motifs. The second large category

stands in contrast to the first. It

includes a total of 43 photos

depicting anti-Yugoslav symbols,

divided by analogy into three

archetypal motifs: the rejection of

NLW (2. 1), the rejection of SFRY

(2. 2) and the rejection of Tito

with the glorification of other

leaders (2. 3). The third large

category includes examples of

“iconoclasts” and the battles

between certain motifs, of which

I’ve recorded 21 examples, whereby

it is practically impossible and to

a larger extent nonsensical to

separate the layers of antagonistic

graffiti and text/images that were

added.

The content of

certain graffiti and street art

conveys a lot more than their bare

quantification. That is why it is

essential to expand the quantitative

approach with the qualitative,

content-focused method. Given that

the pro-Yugoslav examples outnumber

the anti-Yugoslav examples fivefold,

I will henceforth cite more of them.

Some will be left in their original

Serbian/Croatian/ Bosnian or English

form. The text or description of the

graffiti or street art will be

written in cursive while their

location and recording date will be

included in the brackets.

IV. Connotative Level

We will begin with

a Barthesian question: When it comes

to this type of graffiti, which

ideologies or ideological formations

are they fragments of? To find that

out, we must expand denotation and

classification with connotation,

with a quest for broader codes and

with maps of meaning.7 While the

first level of analysis primarily

establishes the similarities in

meaning and their classification

into groups, the second deals with

their differences: I will thus now

focus more on the construction of

meaning through their antagonisms.

In fact, any meaning system connotes

with not only its constitutive

relation, but also its contrast, its

opposing side – the content of the

ideological “thesis” and

“antithesis” is generated from their

mutual polarity.

In regard to their type: the

majority of the graffiti rests on

ideological contradictions –

socialist federalism versus

nationalism. The name of the country

(Jugoslavijo!!! [Yugoslavia!!!]

/Rijeka, 2015/), or its abbreviation

(SFRJ [SFRY] /Ljubljana, 2014/), its

organisations (SKOJ [YCLY – Young

Communist League of Yugoslavia]

/Belgrade, 2012/, JNA [YPA –

Yugoslav People’s Army] /Banja Luka,

2009/, ZKJ [LCY – League of

Communists of Yugoslavia] /Maribor

2011/), symbols (hammer and sickle

/Banja Luka, 2012/, the Coat of Arms

of Yugoslavia /Maribor, 2015/), and

national holidays (Živel 29.

November - Dan republike [Long live

29 November – Republic Day]

/Ljubljana, 1999 and 2010/, 27.

april [27 April] /Maribor, 2014/)

are strung together. The

anti-Yugoslav discourse focuses on

denouncing the organisations of that

era (e.g. JNA zločinci [YPA

criminals] /Zalosce, 1996/), or

establishing the national states of

the Yugoslav people (Nek se ne

zaboravi 10. 4 [10 April must not be

forgotten /Omis, 2005/). As a rule,

the graffiti from one side of the

spectrum are crossed out or amended

with a new text or image: in one

example the symbol of the Ustashas

was crossed out and amended with the

inscription Goli otok and the image

of a five-pointed star (Ljubljana,

2010).

The second ideological opposition

relates to the personality cult:

Tito versus his political opponents.

We can thus find stencils with

Tito’s face (Prizren, 2008;

Ljubljana, towards the end of the

nineties), street-art installations

(Tito’s old statue painted in gold,

bearing a drawn blue heart on its

chest /Maribor, 2015/), graffiti

with his name written in different

ways (I’ve tracked them practically

all over the former Yugoslavia),

streets bearing his name (Tito Way

/Ptuj, 2014/, Titova cesta [Tito’s

Street] /street leading to Trnovo,

2013/), as well as different slogans

and pledges referring to him (Mi smo

Titovi [We are Tito’s] /on the

Sarajevo-Doboj motorway, 2014/, Tito

je naš [Tito is ours] /Zagorje,

2014/). His opponents, of course,

depict his enemies from that time

(Vuk Rupnik, vstani! [Stand up, Vuk

Rupnik!] /Ljubljana, 2014/, Momčilo

Đujić [Momcilo Djujic] /Banja Luka,

2015/, Ante Pavelić [Ante Pavelic]

/Ljubljana, 2012/). Even here we

encounter a fierce wall battle: in

Ljubljana (2015) the original

graffiti saying Josip Broz Tito

vaginalni izbljuvek (vaginal

discharge Josip Broz Tito) was

expanded with a Živio (Long live)

comment adorned with red stars.

The third ideological polarity is

between anti-fascism and fascism. We

encounter repetitions of Partisan

salutes (Smrt fašizmu [Death to

fascism] /its variations occur

across the former Yugoslavia/),

abbreviations of organisations (OF

[LF – Liberation Front] with a

picture of Triglav /re-occurring

across Slovenia/), celebrations of

Partisanism and the rejection of

collaboration (artivistic

intervention Banja Luku su

oslobodili antifašisti, a ne četnici

[Banja Luka was liberated by

anti-fascists, not Chetniks] /Banja

Luka, 2012/, Rozman with an added

swastika /Maribor, 2015/), names and

the faces of fighters (Ivo Lolo

/refers to Ivo Lola Ribar, of

course, Zagreb, 2015/), as well as

conflicts with ideological opponents

(Fašisti v fojbah [Fascists in

foibe] /road towards Ilirska

Bistrica, 2015/). Supporters of the

fascist ideology countered with

salutes, slogans and symbols used by

the Chetniks and Ustashas (S verom u

Boga [With Faith in God] /Banja

Luka, 2015/, Za dom spremni [For

home (land) – ready] /in multiple

locations in Croatia/, with the

letter U and a Catholic cross /in

multiple locations in Croatia/

etc.), self-identification

(Osvetnici Bleiburga [Avengers of

Bleiburg] /on the motorway between

Ilirska Bistrica and Ljubljana,

2014/) and their own sites

(Jasenovac ’43 with the SS sign

/Sarajevo, 2015/). Graffiti authors

have clashed here as well: for

example Smrt levemu terorju! [Death

to left-wing terror!] and the symbol

of the extreme-nationalist group,

the Autonomous Nationalists of

Slovenia, were added to the OF [LF -

Liberation Front], NOB [NLW -

National Liberation War] and red

star symbols (ANSI; Ljubljana,

2011).

V. Ideological Strategies of

Graffiti and Street-Art Subcultures

Graffiti authors and street artists

introduce into political discourse

new forms of expression, a new

language, a new diction, and

something which we will analyse in

further detail – specific strategies

of expression. Graffiti is “a clear

message” – virtually bereft of any

needless adjectives, metaphors,

complications, interpretive openness

or Aesopian ambiguity. It breaks

away from the clench of polysemy and

standardisation. It differs from

other, significantly more elaborate

media used in the antagonistic

construction of the past, e.g.

books, films, shows, poems and

videos etc, which approach the

subject through a scientific or

artistic lens. Not only because it

does not have time for it, but also,

and primarily even, because there is

no need for such an approach: the

graffiti author and street artist

say what they have to say quickly,

bluntly, as effectively as the

Ramones, with knife-sharp precision.

Slovenian street jargon would

describe it as “šus”: nothing should

be added or taken away, we can only

(dis)agree with it. As such,

graffiti are a part of all

contemporary political activism and

are increasingly becoming integrated

into mainstream modes of

communication since the supporters

of current ruling ideologies are

opting to use them all the more

often.8

The first ideological strategy of

pro-Yugoslav and anti-Yugoslav

graffiti and street art is

provocation and criticism: if

aesthetic graffiti represent an

attack on established, “high art”,

if they are a form of counter-art

(kept outside of galleries,

temporary, illegal, unsigned –

simply put: not compliant with the

conventions of institutionalised

art), political graffiti represent

an attack on dominant institutions

and ideologies. That is the origin

of the obsessive use of Yugoslav,

party, Partisan and similar kinds of

jargon and symbolism in places (and

at times) where (and when) it “hurts

the most”. The following examples

demonstrate the importance of

location.9 Slogans like KPJ [LCY –

League of Communists of Yugoslavia]

and Tito could have been spotted on

the building of the archdiocese in

Split (2005); towards the end of the

nineties, one of the government

buildings in Ljubljana was covered

with symbols of the most prominent

factors in the former Yugoslavia

(KPJ [LCY], Tito, SFRJ [SFRY], OF

[LF], Partija [Party]), Svetlana

Makarovic, a poet critical until the

point of revisionism, hung a

conspicuously large red star (2015)

on her balcony at a retirement home

with a direct view of one of

Ljubljana’s main access roads.

Something similar is also occurring

in post-Dayton Bosnia and

Herzegovina where

Yugoslavia-nostalgic graffiti

primarily target the boards of

different entities, or in Croatia

where – during a visit of the

current Culture Minister – anonymous

culprits wrote Hassanbegoviću ustaša

[Hasanbegovic, you’re an Ustasha] on

the entrance wall of the Croatian

History Museum due to his

inclination towards the movement

(2016). This is a typical example of

a discourse twist because the

context decidedly enters into the

field of the text itself. The second

strategy is the affirmation and

continuity of the previous identity

in the present time, i.e. a

resistance to historical revisionism

and the planned expunction of the

Yugoslav and socialist period.

Graffiti with this theme convey that

not everything started in 1991. A

particular example on a secondary

school in Maribor declares that the

students were truly Born in SFRJ,

and Grown in SERŠ [Born in SFRY, and

Grown in SERŠ – Electrical

Engineering and Computer High

School] (2011); however, a stencil

from the late nineties found in

multiple locations across Ljubljana

repeats the slogan Born in SFRJ four

times as it alludes to Springsteen’s

chorus Born in the USA. The third

example is from the Drvar

battlegrounds (2009), where a now

undoubtedly grown-up Dzana from

Sarajevo has identified herself to

this day as Titov pionir [Tito’s

Pioneer] to this day.

Pro-Yugoslav and anti-Yugoslav

graffiti are spatial markers as

well: the third strategy is marking

the turf. The supporters of

Yugoslavia, socialism, Partisanism

and Tito declare that they are

“still here”. The presence of the

SFRJ Coat of Arms (Maribor, 2015),

as well as the simple Tito graffiti,

found practically all across the

former Yugoslavia, are a true

testament to that. The fourth

strategy is the perpetual

antagonisation of the existing, a

counter-punch to the prevalent

discourses and symbolic dominance

over them. A poster in Maribor

(2014) calls attention in this way

to the hardships of many young

people: Rojen v Jugoslaviji – Šolan

v Sloveniji – Nezaposlen v Evropi

[Born in Yugoslavia – Educated in

Slovenia – Unemployed in Europe],

while a graffiti in Labin (2007)

calls for the resurrection of

Yugoslavia: Stvorimo je opet

1945-1990 [Let’s recreate it

1945-1990]. And the final

ideological strategy within the

graffiti and street art culture is

the semiotic guerrilla. One graffiti

from the end of the nineties in

Ljubljana symbolically restores Tito

to his Pioneer salute which

Slovenian punks had ironically

changed towards the end of the

seventies into Za domovino s punkom

naprej! [For the Homeland with punk

– Forward!] – it can now be seen

that it once again says Tito instead

of punk. In Croatia, the original

pro-Ustasha graffiti – the capital

letter U – is commonly changed into

Nisam išao U školu [I didn’t get an

edUcation] (2016). The supporters of

Janez Jansa, a right-wing

politician, have been changing the

original OF [LF] with the Triglav

Partisan symbol into JJ with the

Triglav; while Jansa’s critics keep

restoring the original OF [LF] and

the cycle continues. While the

Triglav – as the undoubtedly most

significant geographic landmark of

Slavic culture – remains the same,

as a common thread, its current

political interpretation is

undergoing changes.

VI. Conclusion: Too Much and Too

Little of Yugoslavia

In the concluding section of the

research paper, I return to the

introductory questions: What kind of

socialist Yugoslavia with all the

contradictions of its “fulfilled

utopia”, about which Suvin (2014)

excellently warns, have street

artists sprayed on the walls of

post-Yugoslav cities? Which of its

aspects are celebrated and which are

denounced? What ideologies are at

play in the diametrically opposed

graffiti motifs on the subject

matter? I find that there are two

answers to the posed questions: a

historical one and a contemporary

one. From the historical

perspective, some graffiti are

exclusively connected to the past.

The analysis of their ideological

formations demonstrates that the

evaluation of those times in our

history is still entirely polarised,

antagonistic. Much like Eco explains

on the example of popular novels

that the “schematisation and

Manichean division is always

dogmatic and intolerant” (1998,

170), there is no dialogue here

either, nor is there a productive

resolution of conflict, nor truce,

nor atonement, nor alternative –

what remains is only the

unbridgeable dichotomy between the

pro-Yugoslav and anti-Yugoslav

sentiments. And so the game of

political ping-pong continues.

These unique ideological twins

depict, mirror and create a

fundamental and unsolvable political

controversy of transition: between

the once-dominant ideologies and

practices (Yugoslav multiculturalism

in the form of brotherhood and unity

in the enthnocultural sphere and of

socialism in the socio-economic

sphere) and their new replacements

(ethno-nationalism in the

enthnocultural sphere and

neoliberalism in the socio-economic

sphere). Anti-Yugoslav,

anti-socialist and nationalist

graffiti are in fact just the

street’s appropriation of dominant

political discourses, reflecting the

“street’s view” of the current

hegemony. Graffiti can therefore

also be what Haraway calls a

“communication of power” (1999,

391), to which we could respond by

referencing Foucault (1978, 95):

“where there is power, there is also

resistance”. If nothing else, the

pro-Yugoslav and pro-leftist

graffiti on urban walls are a form

of expression: they amaze people,

empower them, lift their spirits and

boost their moral strength: (Chaffee

1993, 20). The fact that

pro-Yugoslav sentiments outnumber

their anti-Yugoslav counterparts on

walls attests to the fact that the

former is marginalised, that it

faces a communicational deficit and

that graffiti are one of its rare

media of expression. They are “a

weapon of the weak”, to cite the

effective phrase of James C. Scott.

The fact that there is no

“synthesis” between the Yugoslav

“thesis” and the anti-Yugoslav

“antithesis”, which is still quite

literally demonstrated on walls as a

“red” and “black” truth (literally

red graffiti versus black graffiti),

is a fruitful research topic while

also being exhausting and

obstructive in a political sense.

The reason for this is not the past

in itself: graffiti that refer to

the divisions from the past actually

speak about the confrontations in

the present. The second conclusion

is in my opinion much more important

and of a wider scope, and refers to

the present state. Despite the fact

that the frame of reference for this

kind of urban calligraphy is the

recent past, i.e. some form of

Yugoslav exceptionalism,10 we

encounter in it an explicit

criticism of the current, the

existing, the post-Yugoslav here and

now. It is in fact the actualisation

of (the former) multiculturalism,

the (former) socially more just

society, for the purpose of

criticising (the current)

ethno-nationalism and (the current)

social injustices birthed by the new

capitalism. Much like other media,

graffiti (re)produce relations of

power in society, while also

attacking them – a perpetual

(counter-)hegemonic battle exists

here as well.

In other words, contemporary

political battles are translated

into the time and categories of the

NLW and Yugoslav socialism. Examples

of such graffiti express

disappointment with the outcome of

the transition (Bili smo 3 blok,

sedaj bomo 3 svet [We were the 3rd

block, now we will be the 3rd world]

/Ljubljana, 2010, 2012/; Poslje Tita

dopala nas kita [After Tito we got

dick] /Zagreb, 2015/), an escape

into nostalgic day-dreaming (Dok je

bilo Tita bilo je i šita! [During

Tito there was also shit-o!] /Split,

2011/), or treat historical

revisionism sarcastically (Janezu

Janši v trajni spomin s slikami

pohabljenih žrtev nacizma [For Janez

Jansa to never forget the pictures

of maimed victims of the Nazis]

/Ljubljana, 2009/; Skini Fak Of, Če

bi Hitler praznoval, ne bi ti

slovensko znal with the OF symbol

[Remove the Fuck OFf, if Hitler won,

you wouldn’t be speaking Slovenian]

/Ljubljana, 2010/), glorify

historical leaders while degrading

their successors (Tito je živ, a

Tuđman ne! [Tito is alive, Tuđman is

not!] /Rijeka, 2015/), prefer the

former international community over

the current one, (Bolje Yu nego EU!

[Better Yu than EU!] and the hammer

and sickle /somewhere in Croatia,

2012/), recognise fascism in current

right-wing movements (SKOJ [YCLY],

hammer and sickle above the graffiti

of the right-wing National Alignment

/Banja Luka, 2012/; Antifa Area

Since 1941 added under the Slovenia

graffiti of right-wing organisations

/Ljubljana, 2016/), lash the

opportunism of the current ruling

class (Druže Ramsfeld mi ti se

kunemo… [Comrade Rumsfeld we bow to

you…] /Ljubljana, 2003/), project

current political divisions onto

those from the past (a sticker with

the politicians from the right-wing

Slovenian Democratic Party

(Slovenacka Demokratska Stranka –

SDS) with the added slogan Dost

je!!! domobranske vladavine

[Enough!!! of Home Guard’s rule]

/Ljubljana, 2013/) and ironically

equate the former international

federation of Yugoslavia with the

current international union – the EU

(E/Y/U /Zagreb, 2015/). Something

similar can also be found on the

anti-Yugoslav side where the present

is criticised from the perspective

of the past: current events are

parsed in the categories of the

former Yugoslavia (SDP = Jugoslavija

[SDP = Yugoslavia] /Rijeka, 2015/).

In conclusion: pro-Yugoslav and

anti-Yugoslav political graffiti and

street art are a kind of “Litmus

paper” for current social events and

for evaluating the past. Anonymous

considerations thereof can primarily

be seen on walls. In the view of the

graffiti artists supporting

Yugoslavia, its socialism,

antifascism, etc, such examples are

nowadays far too scarce which is why

with their work they strive to

restore a symbolic “balance” in the

public space by literally restoring

things “to their rightful place”. On

the other hand, according to those

opposed to Yugoslavia and everything

connected to it, such sentiments are

far too frequent which is why

adhering to the generally common

ideological mantra of the

post-Yugoslav right-wing, they

cross-out the “continuation” of the

aforementioned sentiments at every

turn. In light of the increasingly

intensifying economic, political and

overall social situation in

post-socialist post-Yugoslavia, as

well as the ever-deeper polarisation

across the mentioned antagonisms

(socialism vs. neoliberalism,

multiculturalism vs.

ethno-nationalism), we can expect

even more intense street

interventions of this kind.11

VII. Selected bibliography

Abel, Ernest L.; Buckley, Barbara

E., The Handwriting on the Wall –

Toward a Sociology and Psychology of

Graffiti, Greenwood Press, Westport

(Connecticut) & London (UK), 1977.

Abram, Sandi, Komodifikacija ter

komercializacija grafitov in street

arta v treh korakih: od ulic prek

galerij do korporacij: v: Abram, S.;

Bulc, G.; Velikonja, M. (ur.),

Veselo na belo – Grafiti in street

art v Sloveniji, Časopis za kritiko

znanosti, Ljubljana, št. 231-232,

2008, str. 34-49.

Barthes, Roland, Retorika Starih,

Elementi semiologije, ŠKUC,

Filozofska fakulteta, Ljubljana,

1990.

Barthes, Roland, Camera lucida –

Zapiski o fotografiji, ŠKUC,

Filozofska fakulteta, Ljubljana,

1992.

Barthes, Roland, Mythologies,

Vintage, London, Sydney, Auckland,

Bergvlei, 1993.

Benjamin, Walter, Umetnina v času,

ko jo je mogoče tehnično

reproducirati: v: Izbrani spisi,

Studia Humanitatis, Ljubljana, 1998,

str. 145-176.

Castleman, Craig, Getting Up.

Subway Graffiti in New York, The MIT

Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts),

London (UK), 1999.

Chaffee, Lyman G., Political

Protest and Street Art – Popular

Tools for Democratization in

Hispanic Countries, Greenwood Press,

Westport (Connecticut), London (UK),

1993.

Collier, John Jr., Collier,

Malcolm, Visual Anthropology -

Photography as a Research Method,

University of New Mexico Press,

Albuquerque, 1996.

Eco, Umberto, Il superuomo di

massa – Retorica e ideologia nel

romanzo popolare, Bompiani, Milano,

1998.

Foucault, Michel, The History of

Sexuality – Volume I: An

Introduction, Pantheon Books, New

York,1978.

Guiraud, Pierre, Semiologija,

Prosveta – Biblioteka XX vek,

Beograd, 1983.

Hall, Stuart,

Ukodiranje/razkodiranje: v: Luthar,

B.; Jontes, D. (ur.), Mediji in

občinstva, Založba FDV, Ljubljana,

2012, str. 399-412.

Haraway, Donna J., Opice, kiborgi

in ženske – Reinvencija narave,

Študentska založba, Ljubljana, 1999.

Kropej, Monika, Grafitarske bitke.

Sprej kot sredstvo (sovražne)

komunikacije: v: Abram, S.; Bulc,

G.; Velikonja, M. (ur.), Veselo na

belo – Grafiti in street art v

Sloveniji, Časopis za kritiko

znanosti, Ljubljana, št. 231-232,

2008, str. 255-265.

Rose, Gillian, Visual

Methodologies – An Introduction to

Researching with Visual Materials,

Sage, Los Angeles & London & New

Delhi & Singapore & Washington DC,

2012.

Suvin, Darko, Samo jednom se

ljubi. Radiografija SFR Jugoslavije

1945.-72., uz hipoteze o početku,

kraju u suštini, Rosa Luxemburg

Stiftung – Southeast Europe,

Beograd, 2014.

Šterk, Slavko, Umjetnost ulice –

Zagrebački grafiti 1994-2004, Muzej

grada Zagreba, Zagreb, 2004.

Tasić, David, Grafiti, Založba

Karantanija, Ljubljana, 1992.

Velikonja, Mitja, Politika z zidov

– Zagate z ideologijo v grafitih in

street artu; Časopis za kritiko

znanosti; Ljubljana; št. 231-232;

2008, str. 25-32.

Velikonja, Mitja, Nadaljevanje

politike z drugimi sredstvi –

Neofašistični graffiti in street art

na Slovenskem; Časopis za kritiko

znanosti, Ljubljana, št. 251, 2013,

str. 116-126.

Zimmermann, Tanja, Novi kontinent

– Jugoslavija: politična geografija

“tretje poti”; Zbornik za umetnostno

zgodovino, Ljubljana, Vova vrsta

XLVI, 2010, str. 163-188.

Zrinski, Božidar; Stepančič,

Lilijana (ur.), Grafitarji –

Graffitists, Mednarodni grafični

likovni center, Ljubljana, 2004.

|