|

|

|

|

The Albanians of Kosovo in

Yugoslavia – the Struggle

for Autonomy |

|

|

Case

study 2

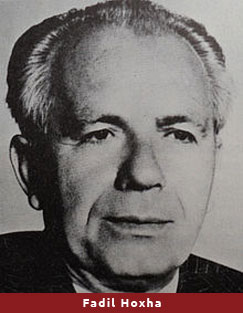

In his memoirs,

Fadil Hoxha recollects how terrible

he felt when Milivoje Bajkić had

yelled at him for writing the

recruits’ names in Albanian while

they were mobilizing men to fight

for Yugoslavia’s final battles.1

Being slammed for using his mother

tongue, he claimed, had made him

aware of the unitarist tendencies

that were becoming evident among the

Serbs in Yugoslavia. This fear of

unitarist approaches, a pejorative

term meaning Serbian centrist

tendencies, was prevalent among the

internationalists, who opposed the

formation of one nation from all the

nations in Yugoslavia.2

Kosovo was

incorporated into Yugoslavia rather

than Albania because of the

influence that the Serbian

communists had, because of the

indifference of Tito on this matter,

and ultimately because of the

inability of the Albanian Partisans

to do anything about it. At a

meeting in Belgrade in 1944, Fadil

Hoxha recalls, Edvard Kardelj had

transmitted Tito’s decision to the

former, that it was perhaps best to

leave Kosovo as part of Serbian

territory to appease the Serbs,

whose insurgence at such a time

would cause a great deal of trouble.3

At one point, even the Montenegrin

Marko Vujaćić had argued to Tito

that the Dukagjini Plain (Metohija

in Serbian) belonged to Montenegro,

but Djilas had countered this

argument by drawing attention to the

fact that if the Dukagjini Plain

were to be incorporated into

Montenegro, thereafter the

Montenegrins would become a minority

in their own republic.4

The worst

incidents after the Partisans

secured control over Kosovo, were

the events that occurred in Tivari,

where 1,670 Albanian recruits were

killed on their way to the Syrmian

front.5 This contributed somewhat to

fostering anti-communist sentiments

in the rural regions of Kosovo,

especially in Drenicë, from where

the majority of recruits were

drawn.By September 1945, the Serbian

Parliament passed a law on the

formation of two autonomous regions

within the republic, namely

Vojvodina and Kosovo and Metohija.6

The Party’s

Agitprop (the Agitation Propaganda

issued by adepartment at the Central

Committee witht he same name)7 seemed

barely successful in Kosovo, nor

significantly so elsewhere.8 However,

the emergence of schools in 1945

teaching in Albanian were welcomed -

where books and teachers came from

Albania proper–and this met with a

positive response and represented a

step forward in embracing the

newly-formed government in Kosovo,

an approach which had not been

practized under the previous

Yugoslav government.9 The calls to

action were mostly led by local

communist cadres, who had the

charisma to go from village to

village and convince the local

peasants about the necessity and

benefits of a united Yugoslavia. It

is evident that there were no

attempts at ideological

indoctrination of the local

populace, at least not until 1947.10

This rang especially true for Kosovo

–indoctrination with

Marxist-Leninist concepts was a

rather strange thing for the local

peasants who had not yet fully

surpassed feudalism. However,

economic and social differences

existed between the semi-urban and

rural groupsand this perhaps

contributed to the fact that urban

classes were more rapid in adopting

Marxist-Leninist theses. In

connection with this assertion,

Ströhl eobserves that the prevalence

of social disparities in socialist

Yugoslavia among the rural and urban

classes was noticeable even during

the later decades of socialist

Yugoslavia.11

After the

establishment of the Federation, the

State Security Department (OZNA)

already began retaliating against

“enemies of the people”. While

initially formed to discover war

crimes, it very swiftly transformed

into the Party’s weapon to eliminate

political enemies. While those

groups that had been considered

enemies during the war such as the

Ustašas, Chetniks, active Germans,

and šiptari,12 were eliminated to some

extent, the latter remained a

perennially stigmatized group within

socialist Yugoslavia.

Having established

political control, the communists

sought to put into motion an

economic revolution by 1947, aimed

at changing Yugoslav society from an

agrarian into an industrial society.13

However, due to extremely backward

and stagnant development, the

process lagged far behind in Kosovo

– it finally occurred in 1957.14 The

initial emergence of socialism and

the formation of cooperatives were

welcomed in Kosovo.15 They were

considered the first step upthe

ladder of economic development. The

cooperatives eventually grew into

small, modern factories.16 There were

not that many families who owned

large pieces of arable land, but

those who did own land, certainly

had to give it away to the state.

And this was not necessarily a bad

thing – indeed, it assured the

instalment of socialism to some

extent and a fairly equal

distribution of goods. It made

certain that the average peasant

could be sustained without having to

work the land of some landowner with

minimal reparation. However, on a

general scale, it became evident

within the second half of the ‘40s

that agricultural production was

insufficient to sustain the general

populace in Kosovo, an issue which

most likely resulted from the

inability to stimulate efficient

production.17 This changed slightly

for the better when modern

agricultural technologies were

introduced and with the introduction

of land production based on

self-management during the period

from 1950 until 1952.18 The peasant

resistance that erupted in

Yugoslavia in 1954 pushed the

government to oust the peasant

workers’ unions as a form of

collective ownership.19

The ideological

monopoly which the Party, renamed

the League of Communists of

Yugoslaviain 1952, enjoyedelsewhere

in public life20 translated poorly to

the average Kosovar Albanian and the

alienation that a great number of

Albanians felt in relation to the

Yugoslav state remained intact.

The emergence of

Yugoslav socialism21 also brought to

light the potential dichotomy of

centralism versus federalism.

Although these political

inclinations were clearly evident on

governmental levels, they took on a

completely different nuance in

Kosovo. The centralist approach of

the Serbian republic, which aimed to

expand its power and influence

vis-à-vis other republics in the

federation, was viewed as a

continuity of Serbian oppression to

Kosovar Albanians. This became

increasingly evident in 1948, where

Kosovo was seen as the proxy

ideological battlefield between the

Albanian Stalinists and the Yugoslav

Communists. Ironically, Enver Hoxha

accused Tito in 1948 of attempting

to incorporate Albania in the

Yugoslav Federation in a blatant

attempt at imperialist colonization,

at the height of the Stalin-Tito

conflict.22

Admittedly,

Albania sent spies to Kosovo, which

conversely transformed the latter

into the “most dangerous place in

the country”.23 In the meantime, some

Kosovo Albanians also left for

Albania.24 In effect, this excused the

state-organized usage of violence

against Kosovar Albanians accused of

treachery, in the form of forced

imprisonment and beatings.25 Fear of a

counter-revolution grew

exponentially, thus legitimizing the

actions of UDBA to raid Albanian

homes for weapons – and those who

didn’t have any weapons would be

forced to buy them so that they

could hand over something when

requested.26 In the meantime, a secret

trial was held in Prizren in July

1956, against nine people charged

with engaging in espionage against

Yugoslavia for Communist Albania.27

Their execution was followed by

rising nationalistic irredentism,

albeit latent.

In his memoirs,

Fadil Hoxha says that this benefited

OZNA28 and Serbia financially –

because according to him “the

weapons were being bought from

Serbia to hand over to OZNA|”.29

Aleksandar Ranković played a major

role in using state mechanisms to

suppress the Albanians, which

resulted in furthering local

inter-ethnic grievances.30 He was of

the opinion that the state security

apparatus was a tool for destroying

“internal and external reaction”.31

Therefore, it comes to no surprise

that harsh action was taken against

Albanians – they were considered

foreign bodies within Yugoslavia who

neither fitted naturally into a

South Slavic state, nor made any

significant attempts to adapt to it.

It is highly likely that ethnic

stigmatization contributed to the

status they earned as a reactionary

force against communism and the

state.

Credible

historical sources regarding this

period and this issue, in

particular, are scanty. However the

action of arms requisition triggered

another reaction -persecution and

subsequently fear among the

Albanians, a factor that might have

influenced some of them to emigrate

to Turkey.

The reconciliation

with the Soviet Union in 1955

increased Yugoslavia’s importance in

the international arena. However,

relations with Albania remained bad.

This resulted in further estranging

Kosovar Albanians, and the ‘50s

stand as a historical testimony to

this inability to adapt. The issue

of the national and ethnic identity

of the Albanians in Kosovo

re-emerged, equating them once again

with the Turks. This resulted in

about 50,000 Albanians emigrating to

Turkey between the years 1953-1954.32

This wave of migrations was

initiated after the Split agreement

between Tito and the Turkish

Minister for Foreign Affairs Mehmet

Fuat Köprülü.33 Granted, a number of

Albanians spoke Turkish in their

homes, a tradition thatsome Albanian

families had absorbed from the

Ottoman past and maintained it as an

oriental remnant. What might have

further contributed to this

situation was the prohibition of

Albanian schools throughout the

existence of the First Yugoslavia.34 The reconciliation

with the Soviet Union in 1955

increased Yugoslavia’s importance in

the international arena. However,

relations with Albania remained bad.

This resulted in further estranging

Kosovar Albanians, and the ‘50s

stand as a historical testimony to

this inability to adapt. The issue

of the national and ethnic identity

of the Albanians in Kosovo

re-emerged, equating them once again

with the Turks. This resulted in

about 50,000 Albanians emigrating to

Turkey between the years 1953-1954.32

This wave of migrations was

initiated after the Split agreement

between Tito and the Turkish

Minister for Foreign Affairs Mehmet

Fuat Köprülü.33 Granted, a number of

Albanians spoke Turkish in their

homes, a tradition thatsome Albanian

families had absorbed from the

Ottoman past and maintained it as an

oriental remnant. What might have

further contributed to this

situation was the prohibition of

Albanian schools throughout the

existence of the First Yugoslavia.34

In his memoirs,

Fadil Hoxha recalls his meeting with

Aleksandar Ranković in an attempt to

explain that identifying themselves

as Turks was a cultural remnant

rather than an actual ethnic

appellation for the Albanians. He

discussed it further to resolve this

issue with Ranković, who thereafter

agreed that Albanians should not

leave Yugoslavia, but only Turks

could do so.35 This evidently referred

to the “free migrants” who were

leaving for Turkey on a voluntary

basis in accordance to Turkey’s Law

on Settlement and who identified

themselves as belonging to the

Turkish ethnicity or identity, which

in itself under the law was not a

clearly defined concept.

Turkish-speaking communities like

the Bosniaks, Pomaks, Circassians,

Albanians and Tatars had benefited

from this law.36 However, the

exclusion from key public positions

and marginalization that Albanians

faced in Yugoslavia certainly pushed

them further into emigrating to

Turkey. The reasons for emigrating

were numerous and varied in nature –

discrimination, persecution and lack

of economic prosperity which

resulted in social and cultural

exclusion from Yugoslav society

seemed to have been the major

incentive behind these migrations.37

It is estimated that more than

80,000 emigrated to Turkey between

1953 and 1966.38

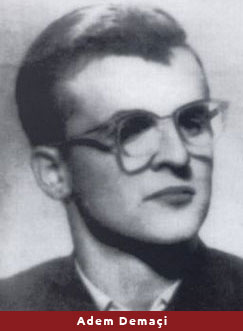

Adem Demaçi, a

young Albanian man, had raised his

voice against these resettlements,

which he believed were attempts by

the Serbian authorities to cleanse

Kosovo of Albanians. He was

imprisoned in 1958 and was released

three years later. In a series of

suppressive measures, as a sign of

vigilance against what was assumed

to be cradles of Albanian

nationalism, the Albanology

Institute was closed in 1955, having

been established only two years

prior.39 These oppressive actions also

contributed to the growing

irredentism amongst Albanians, who

interpreted the closing of the

Albanology Institute as a clear sign

of national oppression against the

development of Albanian

consciousness. Adem Demaçi, a

young Albanian man, had raised his

voice against these resettlements,

which he believed were attempts by

the Serbian authorities to cleanse

Kosovo of Albanians. He was

imprisoned in 1958 and was released

three years later. In a series of

suppressive measures, as a sign of

vigilance against what was assumed

to be cradles of Albanian

nationalism, the Albanology

Institute was closed in 1955, having

been established only two years

prior.39 These oppressive actions also

contributed to the growing

irredentism amongst Albanians, who

interpreted the closing of the

Albanology Institute as a clear sign

of national oppression against the

development of Albanian

consciousness.

After Adem

Demaçi’s release, he founded the

Revolutionary Movement for the

Unification of Albanians, a

clandestine organization which, as

the name suggests, promoted

unification with Albania proper.40 In

1964, he was again put on trial as

the leader of a pan-Albanian

movement (the National Movement for

the Annexation of Kosovo to Albania)

and was sentenced to jail for 15

years.41 Adem Demaçi went on to become

the symbol of Albanian national

resistance.

The discontent of

the Albanians was growing, and as a

sign of resistance, some youngsters

began to unfurl the Albanian

national flag as a gesture of

opposition towards the regime

throughout 1956. This action was

again followed by arrests and

interrogation of the accused by

UDBA.42

Although

principally against irredentism,

Albanian politicians continued their

attempts to promote the wellbeing of

Albanians within the federation.

With the revisions of the Federal

Constitution in 1963, Kosovo was

given the status of an autonomous

province, as opposed to an

autonomous region.43 This was a

positive development for Kosovo,

much to the dismay of some Serbian

authorities, who interpreted it as a

sign that Serbia was losing

dominance over Kosovo. Matters

deteriorated further at the Fourth

Session of the Central Committee of

the League of Communists of

Yugoslavia, where Ranković was

ousted, although this occurrence

paved the way for advancement of the

Kosovo case on a federal level. The

meeting also set into motion the

course of further federalizing the

republics.44 Internal polarization was

already evident in the ‘60s, but the

meeting sent a clear signal to

Serbian high-ranking officials.45

While the student

demonstrations that erupted in

Czechoslovakia, Poland and elsewhere

in Yugoslavia represented a

rebellion against the ruling

oligarchies46,the demonstrations that

erupted in October and November of

1968 in towns throughout Kosovo were

motivated by a slightly different

agenda. The majority of the

protesters who were Albanian

students demanded a republic and an

Albanian university.47 Although there

were reprisals against the

demonstrators, with one demonstrator

even ending up dead and some 22

others who protested in Tetova being

imprisoned, the effect of the

demonstrations helped elevate the

Kosovo case within the political

echelons of Yugoslavia.48 Three years

later, the University of Prishtina

was established in 1971.49 For Hydajet

Hyseni, who would later become a

member of Grupi Revolucionar

(Revolutionary Group) and a

political prisoner, the

demonstrations of 1968 influenced

his national fervor.50

In the meantime,

progressive steps were being taken

to elevate the status of Albanians

within the Yugoslav Federation.

Albanian was acknowledged as an

official language in 1971.51 The

Congress for Unification of the

Albanian Language was held in 1972

in Tirana, where Kosovar Albanian

delegates were sent to participate

at the meeting. The latter supported

the application of a standardized

Albanian language that would be used

in Kosovo, which was mostly based on

the Tosk dialect of Albanian.52

Acceptance of this standard signaled

a national unification of Albanians,

at least within linguistic margins.

The final event that had an

everlasting effect on the

deterioration of Serbian-Albanian

relations was the revisions to the

Constitution in 1974, which

confirmed the status of Kosovo as an

autonomous province.53 This granted a

vast amount of rights to Kosovo in

terms of self-government, much to

Serbia’s defiance.

Demanding a Republic of Kosovo

True to his

fundamental communist beliefs,

Miroslav Krleža was of the opinion

that the right to

self-determination, including

secession as a manifest of rhetoric,

is easily transformedinto

nationalism and irredentism.54 As

such, the national irredentism of

Albanians in Kosovowithin the

Yugoslav communist framework was

ideologically a betrayal of the

communist foundations of denouncing

nationalism as a destructive force

in the communist social system, and

therefore was treated as a

counter-revolutionary force that

must be met with proper retaliation.

However, in the greatdebate on the

sustainability of Yugoslavia as a

multi-ethnic country, it is

historically relevant to acknowledge

the growing nationalism and

irredentism that was being fostered

and nurtured in the other republics

as well, even if they were more

latent in development. These were

crucial impediments to Yugoslav

integration.

The movements in

themselves invited a further

increase in national polarization

and ultimately stimulated the

antagonized parties who, by and

large, rejected the overt centralism

of the federation gravitating

towards Serbia. While the

destruction of Yugoslavia is a

multi-faceted historical debate, to

which one would not do justice in

attempting to analyze it as anything

else but a treatise when discussing

Kosovo’s place in Yugoslavia, one

must confine oneself to addressing

the political role of the communist

cadres and their counter-ideological

colleagues in the historical

developments that occurred in Kosovo

during the last decade of

Yugoslavia’s existence.

Central to this

debate are the irredentist

nationalist organizations, or

clandestine groups, who arguably

laid the foundations of a unified

resistance against Serbian

oppression in Kosovo. However, just

like any other historical event, the

political movements and the Albanian

resistance were not linearly

unified, where many ideological

hurdles had to be overcome and

numerous political alignments

shifted to achieve independence from

Serbia. In this historical

discussion, it would be inaccurate

and superficial to assume that

Kosovo’s history in Yugoslavia was

limited solely to a perpetual

inter-ethnic feud, the Serbian vs.

Albanian duel, and even further

irreverent to adopt the humdrum

“ancient hatreds” as the ubiquitous

reason behind Albanian-Serb

tumultuous relations.

Therefore I adopt

Todorova’s negation that the bloody

history of the Balkans begins within

the geographical realm of Kosovo in

138955, an assertion which wrongfully

asserts that socio-cultural groups

are unchanging and eternal, hence

the medieval hatreds deriving from

fluid ethnic identities in the

Balkan context stand immutable. To

take a position on this issue seems

to be imperative when discussing the

role of Kosovo in the Yugoslav wars,

whose geographical importance in the

medieval context was invoked to stir

up the masses.

In similar

atavistic vein, it has been argued

that the demonstrations of 1981

initiated a domino effect that

exposed the brittleness of the

federation. Meier is quick to

repudiate this assertion by calling

the attention to the “Croatian

Spring” and the following spark of

state repression in Croatia.56 This

assertion is not intended to divert

the reader from the importance and

the effect that the 1981

demonstrations hadon the history of

Yugoslavia’s demise, but rather to

point out that tensions in

Yugoslavia evidently predated the

inter-ethnic feuds in Kosovo, and

that the latter were not prevalent

exclusively in Kosovo.

Nonetheless, it is

also important to address the

argument that national sentiments

were not suppressed in Yugoslavia,

but that they were merely utilized

by national groups to regress entire

social groups into previous feuds.57

While partially true, and perhaps

more valid within the context of

inter-ethnic hatred between the

Slavic nationalities of Yugoslavia,

to negate the existence of ethnic

hostilities between the Serbs and

Albanians prior to 1974 would simply

be historically inaccurate. Frankly,

the argument does not do justice to

the discourse of Albanians in

Yugoslavia – a surplus of historical

evidence suggests that while

national sentiments were utilized to

incite specific political behaviors

at certain periods, the inter-ethnic

feud between the Serbs and Albanians

was in many ways pervasive

throughout Kosovo’s history in

Yugoslavia.

This assertion is

strongly supported by the evident

persecution that Albanians faced

when expressing irredentist, i.e.

nationalistic, stances in the

immediate examples after the

creation of socialist Yugoslavia.

Whether the intent was to persecute

them solely on an ethnic basis or

because nationalistic stances were

incongruent with the reigning

communist ideology is difficult to

assert with certainty. One must note

that the public statements and

official approach of Serbian party

officials in the late ‘80s and early

‘90s justified their actions

precisely by calling on the latter,

and then went on to install a police

state in Kosovo. Perhaps in this

case, the figure of Dobrica Ćosić

provides an excellent example of how

inter-ethnic antagonisms were shaped

throughout the second half of the

20th century, even among the truest

of communists.58

The student

demonstrations of 1981 marked a

turning-point in Kosovo’s history.

The demand to elevate Kosovo’s

status to a republic indicated that

the Albanian masses had grown so

great in numbers that they felt

sufficiently comfortable in their

right to demand such a position

within Yugoslavia, an appeal which

had been thought impossible only

decades earlier. The factors leading

to such a tumultuous situation are

numerous and most likely

complemented each other. The

economic downfall of Kosovo, or

rather its stagnation, had a great

impact on the prosperity of Kosovo’s

young people. The accumulation of

tensions between ethnic groups

furthered the overall grievances,

and left both groups immensely

polarized. The Serbs, on the one

hand, anticipated the ramifications

that a Kosovo comprised of an

absolute majority of ethnic

Albanians would bring – and the

Albanians felt secure enough in

their numerical strength that the

time had come to raise their voice

against what the majority of them

considered to be centuries-long

Serbian oppression.

While there were

Albanians who were vehemently

anti-Yugoslav in their conviction

and furthermore demanded unification

with Albania proper, a great number

of Kosovar Albanians had submerged

within the social and cultural

threads of Yugoslavia, and remained

at least fairly firm in their

beliefs that Yugoslavia could

prevail as a state provided that

Kosovar Albanians would be

recognized as a nation59 and given the

rights they believed they deserved.

The latter usually occupied public

offices and were members of the

League of Communists. While it might

be easier in this discourse to

employ absolute terms and proclaim a

certain group anti-Albanian (or

collaborators with the Yugoslavs)

and deem the other groups devout

nationalists who fought for the

Albanian cause, as seems to be the

current trend in Albanian

historiography, the truth is that

both groups fall somewhere in

between. The existence of

irredentist clandestine Albanian

organizations who proclaimed

themselves Marxist-Leninists60

provides a great example as to how

these political identities were not

clearly defined, and rather than

portraying a division between

ideological alignments among the

Albanians, they best represent the

historical development and

ideological approaches which paved

the way for a political

consciousness of self-determination.

Ultimately, it can be argued that

both the left and the right were

willing to fight for a common cause.61

The fusion of the Marxist-Leninist

and nationalist groups occurred in

1993, when both groups were willing

to set aside their ideological

differences to fight for a common

cause and participate in the Kosovo

Liberation Army.62

The irredentist

Albanian organizations63 operating

during previous decades, had

certainly left a mark on a growing

national consciousness in the

Albanians, and in many ways

influenced forthcoming political

developments by instilling and

promoting nationalistic and

anti-Yugoslav sentiments among the

youth. At the same time, they serve

as a great historical guide on how

the Albanians’ struggle for

independence began from modest

demands to use Albanian as an

official language, to use the

national flag, from establishing the

University of Prishtina, and lastly

to demand independence. The illegal

organizations represented a mainly

latent ideological resistance

against the Yugoslav establishment

because their activity in itself was

limited to an ideological one,

especially so in the previous

decades. While numerous scholars

agree that this struggle was

continuous – in a sense, it was –

such conclusions might indicate that

this struggle had been continuous,

unified and unchanging since the

establishment of the Yugoslav

Federation, which it certainly

wasn’t. While irredentist Albanian

organizations were profoundly active

during the ‘60s, a number of them

ceased their activities during the

‘70s, only to regroup and ignite

another wave of activities in the

‘80s. While most of these

occurrences correspond directly to

cultural, economic and social

developments in Yugoslavia, it is

the demonstrations of ’81 and the

activity of the illegal

organizations of the same decade

that truly mark the social and

cultural developments most specific

to Kosovo. Although the party

officials in Kosovo attempted to

keep these movements under control,

the cohesion gap between the Serbian

authorities and the local Kosovar

Party representatives resulting

under circumstances of Kosovo’s

autonomy64, aggravated the

retaliation of the Serb authorities

against the irredentist movements.

Irredentists, who were labeled

nationalists in Kosovo, were

persecuted throughout Yugoslavia.65 By

1975 and onward, UDBA was arresting

people indiscriminately, which in

itself ignited reactionary

rebellion.66

The riots of 1981

were particularly brutal. They

initially erupted in Prishtina on

the March 26 1981. That same

evening, the then president of the

League of Communists of Kosovo,

spent hours with the students

ensuring them that conditions

wouldimprove at the university.67

However, in the upcoming months they

spread to other cities such as

Podujevë, Gjilan, Vushtrri, Lipjan

etc.68

By April 6, a

state of emergencywas declared in

Kosovo.69 The police retaliated

brutally, with as manyas 300people

beingkilled during these

demonstrations and some 1,000 others

wounded.70 Almost 1,700 people were

imprisoned and 154 awaited trial.71

In 1981, another

nationalist Albanian organization

was established, which was named

Lëvizja Popullore për Republikën e

Kosovës (the Popular Movement for

the Republic of Kosovo), founded by

Hydajet Hyseni, Mehmet Hajrizi and

Nezir Myrtaj.After its fusion with

other clandestine organizations, the

LPRK would play an indispensable

role in forming the Kosovo

Liberation Army. A similar

organization, the irredentist

organization “Lëvizja për Republikën

Socialiste Shqiptare në Jugosllavi”

(The Movement for a Socialist

Albanian Republic in Yugoslavia) was

formed in 1982,initially in

Switzerland by Xhafer Shatri, and

later in Kosovo by Gafurr Elshani

and Shaban Shala.72 The Movement,

which sought the elevation of

Kosovo’s status to a republic within

Yugoslavia, was accused of plotting

unification with Albania proper.73 The

activity of these groups

intersected, yet they often merged

into one group within a geographical

region.74

Between the years

1981 and 1986, around 4,000

Albanians were imprisoned75,

allegedlyfor being involved with

irredentist nationalist

organizations. By 1988, the number

of those imprisoned had reached

584,373.76

This decade also

marks the period when initial

attempts to organizearmed resistance

were being put into effect. Jusuf

Gërvalla, Bardhosh Gërvalla and

Kadri Zeka attempted to organize

armed Albanian resistance based in

Germany, but they were quickly

uncovered by the Serbian police

service in cooperation with the

secret service in cooperation with

the German police.77 They were killed

in Germany in 1982.78 The Albanian

diaspora becameincreasingly active

for the national cause, forming

clubs and societies that would later

serve as a basis to financially

support the Kosovo Liberation Army.

By July 1983, around 55 illegal

groups had been uncovered.79 This decade also

marks the period when initial

attempts to organizearmed resistance

were being put into effect. Jusuf

Gërvalla, Bardhosh Gërvalla and

Kadri Zeka attempted to organize

armed Albanian resistance based in

Germany, but they were quickly

uncovered by the Serbian police

service in cooperation with the

secret service in cooperation with

the German police.77 They were killed

in Germany in 1982.78 The Albanian

diaspora becameincreasingly active

for the national cause, forming

clubs and societies that would later

serve as a basis to financially

support the Kosovo Liberation Army.

By July 1983, around 55 illegal

groups had been uncovered.79

Political alternations in the

Communist League of Kosovo

and the revocation of autonomy

In a speech held

at the Ninth Congress of the Union

of Associations of the Veterans of

the National Liberation War, Pavle

Jovićević addressed the unrest in

Kosovo. He referred to it as

counter-revolutionary activity that

was disrupting the brotherhood and

unity of the people in Kosovo. He

drew attention to the indoctrination

of young Albanians with irredentist

and nationalistic ideas. His

closingremarks called on the ability

of the socialists’ power to

stabilize the situation in Kosovo.80

Undeniably, on an

institutional level, efforts were

made to keep the situation somewhat

under control. The new wave of

Albanian communists was hopeful

abouttheir ability to maintain peace

and stability without furthering

inter-ethnic hatred.However,

tensions were on the rise. The

Albanians were no longer viewed as a

group that belonged in Yugoslavia –

the alienation the former had felt

since Yugoslavia’s inception was

acknowledged by Serbian public

opinion. An article written by

Zvonko Simić in July 1985

calledattention to the low numbers

of Albanian participants in the

National Liberation War.81 The

intention was to argue that

Albanians did not fight for

Yugoslavia, and as such did not

deserve to be part of it.

At the 14th

Conference of Communists in Kosovo

heldin April 1986, Azem Vllasi, who

was previously the leader of the

League of Communist Youth in

Yugoslavia, succeeded Kolë Shiroka

as provincial party chief. A month

later, Sinan Hasani became President

of the Collective Presidency.82 This

political power that was given to

the Albanians allowedthem some power

in exercising their own authority in

the province. Kosta Bulatović, a

Serbian Kosovar, was arrested in

April 1986 because the police found

a copy of a petition that demanded

constitutional changes to Kosovo’s

status in order to stop the alleged

terror of Albanians against Serbs, a

text thathad previously been

published in the press. It turned

out that the police could not say on

whose authority Bulatović was

arrested –eventually it was

understood that he was arrested on

the orders of someone from Belgrade.83

It soonbecame

evident to the Albanian communist

leaders that tensions were being

played on intentionally.84 However, as

Clark noted, it was too late at this

point for the Albanian communists to

turn to the people – they already

were far too antagonized.85 The

released Memorandum of the Serbian

Academy of Sciences and Art of

September 1986, which drew attention

to alleged genocide against the

Serbs, made the ultimate

contribution to the worsening of

inter-ethnic relations up to that

point.86

The President of

the Presidency of Serbia, Ivan

Stambolić remained largelyhesitant

in involving Serbian nationalism

regardingnationalistic sentiments

for Kosovo as a political tool to

garner support and this was used

against him and the other liberals

by Slobodan Milošević in 1987,

subsequently accusing them of having

taken the soft option on Kosovo.87

Dragiša Pavlović, who had warned

about what might happen in the event

of Serbian agitation in Kosovo, was

forced to resign.88 Shaping his

political authority among the

masses, in April 1987 Miloševič

visited Fushë Kosovë (Kosovo Polje)

where Serbian demonstrators were

rallying against alleged oppression

by the Albanians.89 In his speech,

Miloševič referred to the situation

in Kosovo as another exodus since

medieval times of the European

nation from Kosovo, alluding that

Albanians were of oriental heritage.90

During the same period, a vicious

media attack was being launched on

Fadil Hoxha – at the time retired

-who had been a leading Albanian

politician during the demonstrations

of 1968 and 1981. In effect, he was

accused of having supported the

development of nationalist and

irredentist currents.91 The attack on

first-wave communist politicians of

the Second Yugoslavia came at a time

when the Tito era was being

portrayed as a period of oppression

for the Serbs.

By December 1987,

Milosević was still co-operating

with Vllasi on a state level in what

Vllasi assumed was an attempt to

appease the tensions in Kosovo.

However, it quickly became obvious

that Milosević had no realistic

expectation of solving the Kosovo

problem through collaboration with

the local Kosovo leadership.92

After annulling

Vojvodina’s autonomy in 1988,

Miloševič set his sights on Kosovo.

In November 1988, the day the

provincial party board was preparing

to dismiss Kaqusha Jashari, who had

replaced Vllasi in May and stood

also for defending the status of

Kosovo,93 3,000 miners from Trepça

marched to Prishtina in a peaceful

protest. They inspired others to

join the march, which swelled to

almost 300,000 people in total.

Their requests were to retain

Kosovo’s status as an autonomous

province.94

After dismissing

Jashari, Rrahman Morina, Hysamedin

Azemi and Ali Shukriu replaced the

former in party positions. The

newly-appointed officials remained

loyal to Milosevič and helped by

appeasement in the process of

revoking Kosovo’s autonomy.

In February 1989,

revolting against the revocation of

Kosovo’s autonomy, 1,300 miners went

on strike in the mines of Stan Tërg.

Three days later, Morina promised

the miners that he would resign,

which ended the strike. However,

Morina did not deliver his

resignation and the miners admitted

that they had been duped.95 In the

meantime, 215 Albanian intellectuals

signed a petition,which they

addressed to the Serbian Parliament,

where they expressed their

opposition tothese constitutional

changes. A number of them were

dismissed from their jobs or

arrested thereafter.96 Those who were

sent to the prison in Leskovac

endured brutal torture by the

Serbian police.97 By March 1989, Azem

Vllasi, too,had beenarrested.98

The proposed

revocation of Kosovo’s autonomy was

approved in the Parliament of

Kosovo, where 126 delegates were

Albanian out of a total of 190. The

session exerted extreme pressure on

the Albanian delegates, with the

voting being completed in a

completelyerroneous manner. In what

was superficially supposed to be a

democratic session, in utterly

illegitimate and staged settings,

Serbia overruled Kosovo’s autonomy.

The latter regressed to being under

the complete authority of Serbia,

which paved the way for further

oppression and ultimately Serbia’s

attempt to cleanse Kosovo of

Albanians.

Mass protests were

organized in various towns of Kosovo

during early 1989, which met with

harsh retaliation by the Serbian

police. In Podujevë, the Albanian

protesters used stones against the

Serbian police, as well any hard

object they could find, some also

used firearms, and indeed one police

commander was shot dead. Thereafter,

the police began using dumdum

bullets.99

Peaceful resistance and the

emergence of an armed insurgency

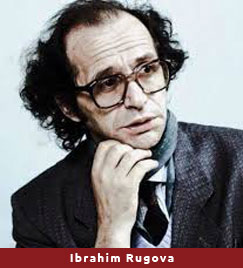

In December 1989

the Democratic League of Kosova

(Lidhja Demokratike e Kosovës) was

established, with Ibrahim Rugova as

president. Rugova was a writer who

had finished part of his education

at the University of the Sorbonne –

he was chosen as a president

precisely because he was thought to

embody the typical Western

intellectual. The party would serve

as the herald for leading political

matters in Kosovo during the ‘90s.

Their approach centered onpeaceful

resistance – an objective which they

hoped would ultimately garner

international support for the

Albanian issue. They also hoped that

the domino effect of the fall of

communist regimes would hit

Yugoslavia before anything tragic

happened.100 While there were other

political parties that were

operating during the period, the LDK

amassed the most support from the

people.101 In December 1989

the Democratic League of Kosova

(Lidhja Demokratike e Kosovës) was

established, with Ibrahim Rugova as

president. Rugova was a writer who

had finished part of his education

at the University of the Sorbonne –

he was chosen as a president

precisely because he was thought to

embody the typical Western

intellectual. The party would serve

as the herald for leading political

matters in Kosovo during the ‘90s.

Their approach centered onpeaceful

resistance – an objective which they

hoped would ultimately garner

international support for the

Albanian issue. They also hoped that

the domino effect of the fall of

communist regimes would hit

Yugoslavia before anything tragic

happened.100 While there were other

political parties that were

operating during the period, the LDK

amassed the most support from the

people.101

Maliqi contends

that during this critical moment

between January and February 1990,

the LDK had a major impact on the

sudden change of pace from violent

unrest to peaceful resistance.102 The

peaceful resistance managed to

deflect the riots, which would have

most certainly been used as a casus

belliby the Serbian military.

Although the pacifist resistance was

not embraced by the illegal

organizations that were already in

the early stages of preparing armed

resistance – it did buy them

sufficient time to prepare for the

guerrilla warfare that was to fully

erupt in 1998.

However, by 1989

the first armed group was formed by

the LPRK in Llap.103 The group changed

their name to LPK (Lëvizja Popullore

e Kosovës) in 1991, the same year

when the group wassetting up its

headquarters in Zürich. At the same

time, its members Xhavit Haliti,

Xhavit Haziri, Ahmet Haxhiu met with

the president of Albania at the

time, Ramiz Alia.104 Ties with Albania

proved to have been extremely

important in the process of training

recruits for the KLA and smuggling

weapons.

By closing down

the Kosovo parliament, on July 2,the

Serbian authorities attempted to

annihilate any legitimate Albanian

authority within Yugoslavia’s

framework. However, the 114 Albanian

delegates held a session in the

courtyard of the Assembly building,

where they declared Kosovo’s

independence.105 The Serbian parliament

dissolved the Kosovo parliament, and

on July 26, the former approved

the Law on Labor Relations under

Special Circumstances, which among

other things, enabled the dismissal

of workers at short notice.106 By 1991,

more than half the Albanians were

dismissed from their

jobs.Thereafter, a police state was

instituted in Kosovo.107

In September 1991,

the Albanian delegates of the Kosovo

parliament called for a referendum

to declare Kosovo’s independence.

99.87% of the voters (constituting

87% of the electorate) voted for

independence.108

By January 1992,

Yugoslavia had already begun to

disintegrate when the European

Community recognized the secession

by Croatia and Slovenia.109

The ‘90s also

correspond with the establishment of

an Albanian parallel system in

Kosovo. This included state

institutions as well as schools that

operated within the framework of the

self-declared independence. The

emergence of Albanian schools within

the parallel system had become

imperative since 1989 when the

Serbian authorities introduced

ethnic-based segregation in schools

– Serbian pupils were not to be

taught in the same classes or

according to the same schedules as

Albanian pupils.110 The establishment

of Albanian schools outside the

Serbian curriculum also meant that

teachers and professors operatedas

units within the institutions of an

independent Kosovo. This also bore a

symbolic importance to Albanians

because it embodied defiance against

Serbian oppression. The academic

staff and the students of the

University of Prishtina were also

banned from using the University’s

property and were therefore forced

to hold classes in private homes.

At the same time

in 1993,serious preparations for

armed resistance were set in motion

in Kosovo. Aware of these

developments, the Serbian police and

military initiated attacks against

people they suspected were involved

in organizing the territorial

defense of Kosovo.111 Between 1992 and

1995, around 135 attacks were

organized against Yugoslav forces.112

The peaceful resistance did not give

up its activity despite harsh

retaliation from the Serbian police

– a peaceful student demonstration

was held in 1997 organized by the

Students’ Union of the University of

Prishtina (1997-1998)113 where police

arrested the leaders of the

Students’ Union and even the rector

of the University of Prishtina at

the time, Ejup Statovci. At the same time

in 1993,serious preparations for

armed resistance were set in motion

in Kosovo. Aware of these

developments, the Serbian police and

military initiated attacks against

people they suspected were involved

in organizing the territorial

defense of Kosovo.111 Between 1992 and

1995, around 135 attacks were

organized against Yugoslav forces.112

The peaceful resistance did not give

up its activity despite harsh

retaliation from the Serbian police

– a peaceful student demonstration

was held in 1997 organized by the

Students’ Union of the University of

Prishtina (1997-1998)113 where police

arrested the leaders of the

Students’ Union and even the rector

of the University of Prishtina at

the time, Ejup Statovci.

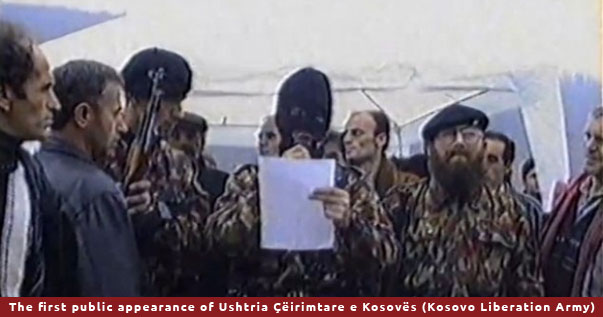

In the meantime,

armed resistance was gaining

momentum. The Dayton Accords did not

foresee Kosovo in the peace

agreement – which left the Albanians

disheartened. In such circumstances,

the emergence of the KLA was not

considered merely an alternative

plan for promoting the Kosovo issue

among international opinion, but

rather the only force that could

make any substantial change. Between

the years 1994-1996, the clandestine

LPK organization was training

soldiers for the Kosovo Liberation

Army and on the November 28, 1997,

marking Albanian National FlagDay,

the KLA made a public appearance at

the funeral of Hasan Geci in Llaushë

of Drenicë.114 The emergence of the KLA

marked the beginning of a

fully-fledged war betweenSerbian

forces and the KLA in Kosovo.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1

Veton Surroi (ed.), Fadil Hoxha në

veten e parë, (Prishtinë, 2010), p.

259. 2

Dejan Jović (ed.), ‘The Kardelj

Concept’, in ‘The Kardelj Concept’:,

Yugoslavia (Purdue University Press,

2009) p. 54.

3

Veton Surroi (ed.), Fadil Hoxha në

veten e parë, pp. 266–270.

4

Rilindja, 12.01.1988, p. 16.

5

Aleksandar Ranković addressed this

issue at a Party session in May

1945, where he remarked that the

incident was a mistake by the

Partisans. Osnivacki Kongres KP

Srbije (8-12 Maj 1945), (Institut za

istoriju Radnickog Pokreta Srbije,

1972), p. 158. Source courtesy of

Anna di Lellio. See also a

survivor’s testimony

http://oralhistorykosovo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/SHABAN-PAJAZITI-ENG-REAL

FINAL_August-4.pdf. See also Howard

Clark, Civil resistance in Kosovo,

(2000), p. 31. See also Miranda

Vickers, Between Serb and Albanian :

A History of Kosovo, (Columbia

University Press: New York, 1998),

p. 143.

6

Christine von Kohl and Wolfgang

Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer Knoten des

Balkan, (Europaverlag: Wien; Zurich,

1992), p. 57. Vojvodina was settled

as an autonomous province and Kosovo

as an autonomous area.

7

Fred Warner Neal, ‘The Communist

Party in Yugoslavia’, The American

Political Science Review, 51 (1957),

p. 90.

8

Carol S. Lilly, ‘Problems of

Persuasion: Communist Agitation and

Propaganda in Post-War Yugoslavia,

1944-1948’, Slavic Review, 53

(1994), pp. 396–397.

9

Veton Surroi (ed.), Fadil Hoxha në

veten e parë, p. 310.

10

Carol S. Lilly, ‘Problems of

Persuasion: Communist Agitation and

Propaganda in Post-war Yugoslavia,

1944-1948’, p. 398.

11

Isabel Ströhle, ‘Of Social

Inequalities in a Socialist society

- The Creation of a Rural Underclass

in Yugoslav Kosovo’, in Rory Archer,

Paul Stubbs, and Igor Duda, eds..

Social Inequalities and Discontent

in Yugoslav Socialism (2016).

12

Zdenko Radelić, ‘The Communist Party

of Yugoslavia and the Abolition of

the Multi-party System’, in Gorana

Ognjenović and Jasna Jozelić, eds.,

Revolutionary Totalitarianism,

Pragmatic Socialism, Transition

(Palgrave Macmillan UK: London,

2016) p. 24. In the revised

constitution of 1968, the Albanian

nation was recognized and the term

‘šiptar’ was replaced by ‘Albanian’.

See Gorana Ognjenović, Nataša

Mataušić, and Jasna Jozelić,

‘Yugoslavia’s Authentic Socialism as

a Pursuit of “Absolute Modernity”’,

in Gorana Ognjenović and Jasna

Jozelić, eds., Titoism,

Self-Determination, Nationalism,

Cultural Memory (Palgrave Macmillan

US: New York, 2016) p. 24. The

contemporary usage of the term

“šiptar” is meant as a pejorative.

13

Holm Sundhaussen, Jugoslawien und

seine Nachfolgestaaten 1943-2011:

Eine ungewöhnliche Geschichte des

Gewöhnlichen, (2012), p. 142.

14

Howard Clark, Civil resistance in

Kosovo, p. 37.

15

Agrarian reform was introduced in

1945, where it was lauded that the

“land belongs to whoever is working

it”. See Ognjenović, Mataušić, and

Jozelić, ‘Yugoslavia’s Authentic

Socialism as a Pursuit of “Absolute

Modernity”’, p. 29.

16

Veton Surroi (ed.), Fadil Hoxha në

veten e parë, p. 301.

17

Veton Surroi (ed.), Fadil Hoxha në

veten e parë, p. 305.

18

Sabrina Petra Ramet, Balkan Babel:

The Disintegration of Yugoslavia

from the Death of Tito to theFall of

Milosevic., (2002), p. 5.

19

Ognjenović, Mataušić, and Jozelić,

‘Yugoslavia’s Authentic Socialism as

a Pursuit of “Absolute Modernity”’,

p. 13. See also John R. Lampe,

Yugoslavia as History: Twice there

was a Country, (Cambridge University

Press: Cambridge; New York, 1996),

p. 233.

20 Sergej Flere and Rudi

Klanjšek, ‘Was Tito’s Yugoslavia

totalitarian?’, Communist and

Post-Communist Studies, 47 (June

2014), p. 238.

21 Which deemed it

‘self-managing socialism’ and

‘nonaligned’. See Zachary Irwin,

‘The Untold Stories of Yugoslavia

and Nonalignment’, in Gorana

Ognjenović and Jasna Jozelić, eds.,

Revolutionary Totalitarianism,

Pragmatic Socialism, Transition

(Palgrave Macmillan UK: London,

2016) p. 140.

22 Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, p. 58.

23 Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, p. 59.

24 Veton Surroi (ed.), Fadil

Hoxha në veten e parë, p. 321.

25 Emine Arifi - Bakalli, ‘Një

mikrosintez për Kosovën 1945-1997’,

in ‘Një mikrosintez për Kosovën

1945-1997’, Përballje

historiografike (Instituti

Albanologjik - Prishtinë: Prishtinë,

2015) p. 113.

26 Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, p. 59. See also

Howard Clark, Civil resistance in

Kosovo, p. 37.

27 Viktor Meier, Yugoslavia: A

History of its Demise, (1999),

p. 26.

28 By March 1946 OZNA was

already reorganized, and the section

responsible for civilian

counter-intelligence was transformed

into the Directorate for State

Security (Uprava državne

bezbjednosti, UDBA). See Zdenko

Radelić, ‘The Communist Party of

Yugoslavia and the Abolition of the

Multi-party System’, p. 18.

29 Veton Surroi (ed.), Fadil

Hoxha në veten e parë, p. 298.

30 Frederick F. Anscombe, ‘The

Ottoman Empire in Recent

International Politics-II: The Case

of Kosovo’, The International

History Review, 28 (2006), p. 760.

31 Zdenko Radelić, ‘The

Communist Party of Yugoslavia and

the Abolition of the Multi-Party

System’, p. 18. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

32 Veton Surroi (ed.), Fadil

Hoxha në veten e parë, p. 297.

33 Nikolina Rajkovic, ‘The

Post-Second World War Emigration of

Yugoslav Muslims to Turkey

(1953-1968)’, (Central European

University), p. 63.

34 Vickers, Between Serb and

Albanian : A History of Kosovo, p.

103.

35 Veton Surroi (ed.), Fadil

Hoxha në veten e parë, p. 297.

36 Kemal Kirişçi, ‘Post-Second

World War Emigration from Balkan

Countries to Turkey’, New

Perspectives on Turkey, 12 (April

1995), p. 61.

37 Emine Arifi - Bakalli, ‘Një

mikrosintez për Kosovën 1945-1997’,

p. 114. Rozita Dimova, From past

necessity to contemporary friction:

Migration, class and ethnicity in

Macedonia, (Max Planck Institute for

Social Anthropology: Halle/Saale,

2007). See also Hajredin Hoxha,

Arsyet, faktorët dhe pasojat e

lëvizjeve demografike dhe migruese

të popullsisë së Kosovës dhe të

pjesëtarëve të popullsisë shqiptare

në Jugosllavi, Përparimi, nr. 7,

Prishtinë, 1976.

38 Viktor Meier, Yugoslavia: A

History of its Demise, p. 26.

100,,000 according to Emine Bakalli.

See Emine Arifi - Bakalli, ‘Një

mikrosintez për Kosovën 1945-1997’,

p. 114. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

39 Howard Clark, Civil

Resistance in Kosovo, p. 37. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

40 Howard Clark, Civil

Resistance in Kosovo, p. 38.

41 Viktor Meier, Yugoslavia: A

History of its Demise, p. 26.

42 Howard Clark, Civil

Resistance in Kosovo, p. 38.

43 Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, p. 59.

44 Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, p. 63. See also

Četvrti plenum Centralnog komiteta

Saveza komunista Jugoslavije,

(Komunist, 1966), pp. 70–74.

45 Latinka Perović, ‘Dobrica

Ćosić and Josip Broz Tito—A

Political and Intellectual

Relationship’, in Gorana Ognjenović

and Jasna Jozelić, eds, Titoism,

Self-Determination, Nationalism,

Cultural Memory (Palgrave Macmillan

US: New York, 2016) p. 115.

46 Hrvoje Klasić, ‘Tito’s 1968

Reinforcing Position’, in Gorana

Ognjenović and Jasna Jozelić, eds.,

Revolutionary Totalitarianism,

Pragmatic Socialism, Transition

(Palgrave Macmillan UK: London,

2016) p. 168.

47 Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, p. 67.

48 Howard Clark, Civil

resistance in Kosovo, p. 39.

49 Shkëlzen Maliqi, ‘Die

politische Geschichte des Kosovo’,

in Dunja Melčić, ed., Der

Jugoslawien-Krieg: Handbuch zu

Vorgeschichte, Verlauf und

Konsequenzen (VS Verlag für

Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden,

1999) p. 128.

50

http://oralhistorykosovo.org/wp-content/uploads/

2016/04/Hydajet-Hyseni_ENG_Final.pdf,

p. 8.

51 Ognjenović, Mataušić, and

Jozelić, ‘Yugoslavia’s Authentic

Socialism as a Pursuit of “Absolute

Modernity”’, p. 22.

52 Veton Surroi (ed.), Fadil

Hoxha në veten e parë, p. 325. See

also Robert C. Austin, ‘Greater

Albania: The Albanian State and the

Question of Kosovo, 1912-2001’, in

John R. Lampe and Mark Mazower,

eds., Ideologies and national

identities the case of

twentieth-century Southeastern

Europe (Central European University

Press, 2004) p. 239.

53 Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, p. 63.

54 Albert Bing, ‘Tito(ism) and

National Self-Determination’, in

Gorana Ognjenović and Jasna Jozelić,

eds., Titoism, Self-Determination,

Nationalism, Cultural Memory

(Palgrave Macmillan US: New York,

2016) p. 82. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

55 Mariia Nikolaeva Todorova,

Imagining the Balkans, (2009), p.

186.

56 Viktor Meier, Yugoslavia: A

History of its Demise, pp. 16s–17.

On a similar vein, Isa Blumi

contends a similar approach in

refuting the “powder keg effect” of

Albanians in the Balkans, which had

become the epitome of publicist work

in regards to the Balkans. See Isa

Blumi, ‘The Commodification of

Otherness and the Ethnic Unit in the

Balkans: How to Think about

Albanians’, East European Politics

and Societies, 12 (September 1998),

p. 535. In refuting the

“ancient-hatred” hypothesis see also

Noel Malcolm, ‘What Ancient

Hatreds?’, Foreign Affairs, 78

(1999), pp. 130–134., Arjan Hilaj,

‘The Albanian National Question and

the Myth of Greater Albania’, The

Journal of Slavic Military Studies,

26 (July 2013), p. 397.

57 Dejan Jović, ‘The

Disintegration of Yugoslavia: A

Critical Review of Explanatory

Approaches’, European Journal of

Social Theory, 4 (2001), p. 104. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

58 Latinka Perović, ‘Dobrica

Ćosić and Josip Broz Tito—A

Political and Intellectual

Relationship’. In regards to this

issue see also Thomas Bremer,

Serbiens Weg in den Krieg:

Kollektive Erinnerung, nationale

Formierung und ideologische

Aufrüstung, (Berlin-Verl. Spitz:

Berlin, 1998). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

59 Then again, the concept of

nation and nationality were never

clearly defined in the

constitutional system. In 1981 alone

there were 1.7 million Albanians in

Yugoslavia, 570,000 Montenegrins and

1.3 million Macedonians, however the

first group was considered a

nationality and the two last groups

a nation. See Viktor Meier,

Yugoslavia: A History of its Demise,

pp. 8–9.

60 For example Organizata

Marksiste-Leniniste e Kosovës (the

Marxist-Leninist Organization of

Kosova), established in 1969, which

promoted the establishment of the

Republic of Kosovo. See Sabile

Keçmezi-Basha, Organizatat dhe

grupet ilegale në Kosovë 1981-1989:

Sipas aktgjykimeve të gjykatave

ish-jugosllave, (Instituti i

Historisë - Prishtinë: Prishtinë,

2003), pp. 101–108. Similar to

‘Partia Komuniste

Marksiste-Leniniste e shqiptarëve në

Jugosllavi’ (The Marxist-Leninist

Communist Party of Albanians in

Yugoslavia), who sought unification

in one territorial unit of

Albanian-inhabited lands in

Yugoslavia. See Sabile

Keçmezi-Basha, Organizatat dhe

grupet ilegale në Kosovë 1981-1989:

Sipas aktgjykimeve të gjykatave

ish-jugosllave, pp. 169–87.

61 James Pettifer, Ushtria

Çlirimtare e Kosovës: Nga një luftë

e fshehtë në një kryengritje të

Ballkanit 1948-2001, (Onufri:

Tiranë, 2013), p. 75.

62 James Pettifer, Ushtria

Çlirimtare e Kosovës: Nga një luftë

e fshehtë në një kryengritje të

Ballkanit 1948-2001, p. 92.

63 Nominally referred to as

‘illegal Albanian organizations’ in

Albanian. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

64 Sabrina Petra Ramet, Balkan

Babel: The Disintegration

of Yugoslavia from the death of Tito

to the fall of Milosevic.,

p. 12.

65 Viktor Meier, Yugoslavia: A

History of its Demise, p. 17.

66

http://oralhistorykosovo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/

04/Hydajet-Hyseni_ENG_Final.pdf, p.

12.

67 Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, p. 78.

68 Sabile Keçmezi-Basha,

Organizatat dhe grupet ilegale në

Kosovë 1981-1989: Sipas aktgjykimeve

të gjykatave ish-jugosllave, pp.

62–63.

69 Viktor Meier, Yugoslavia: A

History of its Demise, p. 22.

70 Sabile Keçmezi-Basha,

Organizatat dhe grupet ilegale në

Kosovë 1981-1989: Sipas aktgjykimeve

të gjykatave ish-jugosllave, p. 66.

See also Howard Clark, Civil

resistance in Kosovo, p. 42.

71 Sabile Keçmezi-Basha,

Organizatat dhe grupet ilegale

në Kosovë 1981-1989: Sipas

aktgjykimeve të gjykatave

ish-jugosllave, p. 64.

72 James Pettifer, Ushtria

Çlirimtare e Kosovës: Nga një luftë

e fshehtë në një kryengritje të

Ballkanit 1948-2001, p. 301.

73 Sabile Keçmezi-Basha,

Organizatat dhe grupet ilegale në

Kosovë 1981-1989: Sipas aktgjykimeve

të gjykatave ish-jugosllave, p. 151.

The movement transformed several

times, initially being named Zëri i

Kosovës (The Voice of Kosovo),

thereafter Fronti i Kuq (The Red

Front), and lastly Fronti i Kuq

Popullor (The People’s Red Front).

74 Sabile Keçmezi-Basha,

Organizatat dhe grupet ilegale në

Kosovë 1981-1989: Sipas aktgjykimeve

të gjykatave ish-jugosllave, p. 152.

75 Viktor Meier, Yugoslavia: A

History of its Demise, p. 32.

76 Howard Clark, Civil

resistance in Kosovo, p. 43. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

77 James Pettifer, Ushtria

Çlirimtare e Kosovës: Nga një luftë

e fshehtë në një kryengritje të

Ballkanit 1948-2001, p. 75.

78 James Pettifer, Ushtria

Çlirimtare e Kosovës: Nga një luftë

e fshehtë në një kryengritje të

Ballkanit 1948-2001, p. 301. See

also Howard Clark, Civil resistance

in Kosovo, p. 43.

79 Sabrina Petra Ramet, Balkan

Babel: The Disintegration

of Yugoslavia from the Death of Tito

to the Fall of Milosevic.,

p. 315. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

80 Rajko Goranović, Deveti

Kongres saveza udruženja boraca

Narodno Oslobodolilačkog rata

Jugoslavije, (Četvrti jul: Beograd,

1982), pp. 139–141.

81 NIN, 7.07.1985. The article

also criticizes the Albanian

publication series of the publishing

house Rilindja, entitled Në flakën e

revolucionit (At the hearth of

revolution), with the first volume

published in 1966. It claims the

publication falsified the number of

Albanian victims fallen during the

National Liberation war.

82 Viktor Meier, Yugoslavia: A

History of its Demise, p. 35.

83 Nevenka Tromp, Prosecuting

Slobodan Milosevic: The Unfinished

Trial, (2016), p. 50.

84 Nevenka Tromp, Prosecuting

Slobodan Milosevic: The Unfinished

Trial, p. 50.

85 Howard Clark, Civil

resistance in Kosovo, p. 47.

86 Enver Hoxhaj, ‘Das Memorandum

der Serbischen Akademie der

Wissenschaften und Künste und die

Funktion politischer Mythologie im

kosovarischen Konflikt’,

Südosteuropa, 51 (2002), p. 6. See

also Sabrina Petra Ramet, Balkan

Babel: The Disintegration of

Yugoslavia from the Death of Tito to

the Fall of Milosevic., p. 20. The

Memorandum was contemporary with a

petition signed by some two hundred

Serbian intellectuals which called

for attention to the supposed

genocide committed against the Serbs

in Kosovo specifically by Albanians,

and which urged for ‘deep social and

political changes’ to halt the

genocide in Kosovo. See Branka

Magaš, The destruction of

Yugoslavia: Tracking the Break-up

1980-92, (New York : Verso: London,

1993), pp. 49–52.

87 Branka Magaš, The De

struction of Yugoslavia: Tracking

the break-up 1980-92, pp. 109–110.

88 Viktor Meier, Yugoslvia: A

History of its Demise, p. 38. The

rift within the Party was more or

less not centered solely on the

manner of tackling the Kosovo issue.

Magaš argues that the crisis was a

result of conflicting ideas on how

to deal with the economic crisis

that had overtaken the country

combined with the struggle of

overcoming nationalist

counter-revolution prevalent in the

republics. See Branka Magaš, The

Destruction of Yugoslavia: Tracking

the Break-up 1980-92, p. 203.

89 Viktor Meier, Yugoslavia: A

History of its Demise, p. 38.

90 Zekeria Cana, Apeli 215 i

intelektualëve shqiptarë, (Rilindja:

Prishtinë, 2001), p. 11.

91 Rilindja, 21.10.1987, p. 5.,

Rilindja, 9.12.1987, p. 5.,

Rilindja, 10.12.1987, p. 5. For the

role of the media in inciting

antagonistic stances amongst the

masses in Yugoslavia see Sabrina

Petra Ramet, Balkan Babel: The

Disintegration of Yugoslavia from

the Death of Tito to the Fall of

Milosevic., pp. 40–41.

92 Borba, 9.12.1987, p. 3.

Branka Magaš, The Destruction of

Yugoslavia: Tracking the Break-up

1980-92, p. 109.

93 Sabrina Petra Ramet, Balkan

Babel: The Disintegration

of Yugoslavia from the Death of Tito

to the Fall of Milosevic.,

p. 29.

94 Howard Clark, Civil

Resistance in Kosovo, p. 48.

95 Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, pp. 112–114. See

also Branka Magaš, The destruction

of Yugoslavia: Tracking the break-up

1980-92, p. 180.

96 Shkëlzen Maliqi, ‘Die

politische Geschichte des Kosovo’,

p. 129. See also Zekeria Cana, Apeli

215 i intelektualëve shqiptarë, p.

286. See also Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, p. 118. See also

Shkëlzen Maliqi, ‘Why the Peaceful

Resistance Movement in Kosovo

Failed’, in ‘Why the Peaceful

Resistance Movement in Kosovo

Failed’, After Yugoslavia:

Identities and Politics within the

Successor States p. 45.

97 Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, p. 118.

98 Sabrina Petra Ramet, Balkan

Babel: The Disintegration of

Yugoslavia from the Death of Tito to

the Fall of Milosevic., p. 31.

99 Christine von Kohl and

Wolfgang Libal, Kosovo: Gordischer

Knoten des Balkan, pp. 116–118. For

the demonstrations of 1988, 1989 see

also Blerim Shala, Kosovo - krv i

suze, (Zalozba alternativnega tiska:

Ljubljana, 1990). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

100 Shkëlzen Maliqi, ‘Die

politische Geschichte des Kosovo’,

p. 130.

101 UJDI (Udruženje za

jugoslovensku demokratsku

inicijativu), founded by Shkëlzen

Maliqi and Veton Surroi in 1988 did

not garner mass support in contrast

to LDK. By the end of 1990, there

was a pluralist system of political

parties established in Kosovo.

102 Shkëlzen Maliqi, ‘Why the

Peaceful Resistance Movement in

Kosovo Failed’, p. 45. Hajzer

Hajzeraj who was accused by Serbian

authorities for serving as Minister

of Defense for Kosovo, later

admitted that the LDK had issued an

order to construct a territorial

defense. See Howard Clark, Civil

Resistance in Kosovo, p. 65.

103 James Pettifer, Ushtria

Çlirimtare e Kosovës: Nga një luftë

e fshehtë në një kryengritje të

Ballkanit 1948-2001,

p. 302.

104 James Pettifer, Ushtria

Çlirimtare e Kosovës: Nga një luftë

e fshehtë në një kryengritje të

Ballkanit 1948-2001, p. 303.

Pettifer contends that Ramiz Alija

was interested in styling the Kosovo

Liberation Army along the lines of

the Irish Republican Army. See James

Pettifer, Ushtria Çlirimtare e

Kosovës: Nga një luftë e fshehtë në

një kryengritje të Ballkanit

1948-2001, p. 78.

105 Sabrina Petra Ramet, Balkan

Babel: The Disintegration

of Yugoslavia from the Death of Tito

to the Fall of Milosevic.,

p. 31.

106 Howard Clark, Civil

Resistance in Kosovo, p. 73.

107 Howard Clark, Civil

Resistance in Kosovo, pp. 74–81.

108 Howard Clark, Civil

Resistance in Kosovo, p. 82.

109 Bette Denich, ‘Dismembering

Yugoslavia: Nationalist Ideologies

and the Symbolic Revival of

Genocide’, American Ethnologist, 21

(1994), p. 368.

110 Howard Clark, Civil

resistance in Kosovo, pp. 95–98. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

111 Howard Clark, Civil

resistance in Kosovo, p. 62. James.

Pettifer, The Kosova Liberation

Army : underground war to Balkan

insurgency, 1948-2001, (Columbia

University Press: New York, 2012),

p. 90.

112 James Pettifer, Ushtria

Çlirimtare e Kosovës: Nga një luftë

e fshehtë në një kryengritje të

Ballkanit 1948-2001,

p. 95. *Picture courtesy of Milot

Caka and Rina Krasniqi

113 Howard Clark, Civil

resistance in Kosovo, p. 152. See

also Bujar Dugolli, 1 tetori i

kthesës - Lëvizja studentore

1997-1999, (Universiteti i

Prishtinës: Prishtinë, 2013). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

114 James Pettifer, Ushtria

Çlirimtare e Kosovës: Nga një luftë

e fshehtë në një kryengritje të

Ballkanit 1948-2001,

p. 127. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|