|

Case

study 4

1. INTRODUCTION

Over four and a

half decades of its existence

socialist Yugoslavia has amended

four constitutions.1 This very fact

indicated the problems and

challenges the Yugoslav federation

had been faced with continually

since its establishment.2 Responses

to existing circumstances, domestic

and international, were being

searched for in different

constitutional solutions that were

also used as guideposts to new modes

of functioning of Yugoslav

political, economic and social

system. The same as the first two –

proclaimed in 1946 and 1953 – that,

due to specific situations the

country found itself in (the end of

the war and the (Communist

Information Bureau) Comintern

Resolution), placed the ongoing

political developments in the

forefront and were, as Vladimir

Bakarić put it, more “concerned with

the past,”3 not even the third

Constitution of 1963 managed to

respond to the challenges facing the

Yugoslav federation. Though passed

in by far more stable political

situation than its predecessors,

this Constitution was declared

against the turbulent economic and

political backdrop of the late 1950s

and early 1960s. But that was the

time when the Yugoslav “economic

wonder” of the country’s

development, society’s modernization

and growing standards of living was

slowly losing momentum. Heavier and

heavier burden of economic problems

pressing the country resulted in a

Pandora’s Box: other problems that

had been placed in the back seat in

the previous period due to economic

growth emerged. In early 1974

socialist Yugoslavia got its fourth

Constitution. By its contents, and

consequences as well, this was

probably the most complex project

for defining internal relations in

the Yugoslav federation. It has to

be stressed, however, that

constitutional provisions voted in

on February 21, 1974 by the Federal

Assembly had been backed with

years-long exchanges, mutual

adjustments and negotiations.

Despite the proclaimed agreement in

stances, the said process had

frequently revealed radically

different views development of

Yugoslavia and its socialism.

Inter-republican and interethnic

relations, the role of the federal

center and the future of

self-government at all levels and in

all segments of the society were

just some of the issues reflecting

the controversy of the debate on

constitutional reform. Declaration

of the Constitution did not put an

end to these disputes and

antagonisms. And in the last decade

of socialist Yugoslavia’s existence,

this very Constitution will stand

for a legal starting point in the

country’s disintegration.

2. SELF-GOVERNMENT AND

(DE)CENTRALIZATION

The role assigned

to (central) government or, to put

it more precisely its power, was

among main characteristics of and at

the same time a specific difference

between Yugoslav and Soviet models

of socialism-building. Following the

Cominform Resolution Yugoslav

communists opted for a

sociopolitical experiment meant to

prove their distancing from

Stalinist understanding of Marx’s

and Engels’ ideas of a state’s

“dying out.” Accordingly, the state

should be deprived of power – as

soon and as much as possible – and

the concept of workers’ and social

self-government should be the means

for attaining that goal.4 However,

the said concept did not imply that

just the federal center should be

made weaker. A radical

decentralization should equally

weaken and then eliminate the

predominance of the federation, but

republican centers of power as well.

On the other hand, local

self-governments and direct

producers – i.e. workers via their

workers’ councils – should be key

players in political and economic

development of the society. What

happened in real life was quite

contrary to this idea

notwithstanding all the proclaimed

principles. In fear of economic

anarchy, powers in (planning)

economy remained invested in the

federation.5 The biggest losers of

this policy were republics. The

emphasis placed on social and

workers’ self-government at lowest

levels, and the political

leadership’s stance that national

issues had been settled (in the war,

i.e. revolution) did not encourage

development of Yugoslav federalism

but, on the contrary, strengthened

centralistic tendencies. Annulment

of the Chamber of Peoples in the

federal assembly also testified that

decentralization, in the form of

self-government, was carried out at

the detriment of federalism. Under

constitutional provisions of 1946

the Assembly of the Federal People’s

Republic of Yugoslavia had two

chambers – the Federal Chamber and

the Chamber of Peoples – the latter

composed of representatives of all

republics and provinces. This

provision was amended in the

Constitutional Law of 1953: the

Chamber of Peoples was replaced by

the Chamber of Producers.6

In the late 1950s

the country’s stabilized

international standing, growing

economic prosperity but also many

half-finished solutions in the

self-government system gave rise to

first debates on functioning of the

Yugoslav federal model. Dušan

Bilandžić takes that the issue was

firstly placed on the agenda in

1958, on February 6, at the “secret”

meeting assembling members of the

Executive Committee of the Central

Committee of the League of

Communists of Yugoslavia and top

brass of republican and federal

institutions.7 The strike staged by

miners in Trbovlje, the first bigger

expression of the working class’

dissatisfaction after the end of

World War II, triggered off a deeper

analysis of Yugoslavia’s

sociopolitical situation. The

analysis was mostly focused on the

relationship between republics and

the federation, and relations

between the republics but on

interethnic relations as well.

Despite worrisome theses voiced

throughout the debate, the party

leadership decided to pursue along

the same course of social

development. Thus the problems were

not overcome but, moreover, under

the new circumstances marked by

negative influence of the economy,

became factors of instability that

weighted on Yugoslavia until its

disintegration. To put it simply,

the basic problem boiled down to the

calculation of the amounts of “who”

was giving to the federation and

“who” getting from it. Republics

established as socialist but also

nation-states added a new dimension

to the antagonism between developed

and underdeveloped regions,

inherited from the Kingdom of

Yugoslavia. One of major goal of

centralized economic and investment

policy was to decrease the existing

disproportion. As long as economic

growth was high everyone was happy

with this policy. The underdeveloped

were being paid huge sums from the

common treasury to develop their

economic resources and social

standard, whereas the developed

benefited from their better starting

point in industrialization,

infrastructure and common market

opportunities, as well as lower

prices they paid for raw material.8

Disagreements between supporters of

the centralized planned economy and

advocates of decentralization on the

principles of self-government were

evident throughout the 1950s. At

this early stage the resistance to

centralism did not automatically

imply advocacy for more rights to be

invested in republics. This was

probably best illustrated in the

stances of Vladimir Bakarić, the

number one of Croatian communist

and, together with Edvard Kardelj,

strong advocate for economic and

political decentralization. In his

view, the self-government reform

should have proportionally decreased

the powers of federal and republican

institutions. Stronger republican

statehood (including Croatia’s) is

the expression of nationalism, he

said, and contrary to interests of

the (Croatian) people.9 Advocates of

decentralization argued that the

struggle against centralism and

planned economy was in the interest

of all citizens of Yugoslavia rather

than just one people or republic.

However, economic growth of the

developed slowed down for the

benefit of the underdeveloped was

also not in the interest of the

entire socialist community. And this In the late 1950s

the country’s stabilized

international standing, growing

economic prosperity but also many

half-finished solutions in the

self-government system gave rise to

first debates on functioning of the

Yugoslav federal model. Dušan

Bilandžić takes that the issue was

firstly placed on the agenda in

1958, on February 6, at the “secret”

meeting assembling members of the

Executive Committee of the Central

Committee of the League of

Communists of Yugoslavia and top

brass of republican and federal

institutions.7 The strike staged by

miners in Trbovlje, the first bigger

expression of the working class’

dissatisfaction after the end of

World War II, triggered off a deeper

analysis of Yugoslavia’s

sociopolitical situation. The

analysis was mostly focused on the

relationship between republics and

the federation, and relations

between the republics but on

interethnic relations as well.

Despite worrisome theses voiced

throughout the debate, the party

leadership decided to pursue along

the same course of social

development. Thus the problems were

not overcome but, moreover, under

the new circumstances marked by

negative influence of the economy,

became factors of instability that

weighted on Yugoslavia until its

disintegration. To put it simply,

the basic problem boiled down to the

calculation of the amounts of “who”

was giving to the federation and

“who” getting from it. Republics

established as socialist but also

nation-states added a new dimension

to the antagonism between developed

and underdeveloped regions,

inherited from the Kingdom of

Yugoslavia. One of major goal of

centralized economic and investment

policy was to decrease the existing

disproportion. As long as economic

growth was high everyone was happy

with this policy. The underdeveloped

were being paid huge sums from the

common treasury to develop their

economic resources and social

standard, whereas the developed

benefited from their better starting

point in industrialization,

infrastructure and common market

opportunities, as well as lower

prices they paid for raw material.8

Disagreements between supporters of

the centralized planned economy and

advocates of decentralization on the

principles of self-government were

evident throughout the 1950s. At

this early stage the resistance to

centralism did not automatically

imply advocacy for more rights to be

invested in republics. This was

probably best illustrated in the

stances of Vladimir Bakarić, the

number one of Croatian communist

and, together with Edvard Kardelj,

strong advocate for economic and

political decentralization. In his

view, the self-government reform

should have proportionally decreased

the powers of federal and republican

institutions. Stronger republican

statehood (including Croatia’s) is

the expression of nationalism, he

said, and contrary to interests of

the (Croatian) people.9 Advocates of

decentralization argued that the

struggle against centralism and

planned economy was in the interest

of all citizens of Yugoslavia rather

than just one people or republic.

However, economic growth of the

developed slowed down for the

benefit of the underdeveloped was

also not in the interest of the

entire socialist community. And this

exactly became a crucial economic

and political problem in the

functioning of the Yugoslav

federation. “Developed regions,

those that made bigger progress,

must be lagging in the domain of

investment; otherwise, those that

are not made progress cannot develop

themselves,” he said in 1960, adding

that due to such policy Croatia had

been lagging behind less developed

republics for the past 15 years.10 In

Bakarić’s opinion – to be accepted

by the majority of the Croatian

leadership – the federation should

become much more flexible (to

different solutions), i.e. it should

“flex.”11 Motives of the opponents of

decentralization were different. For

some, loss of the monopoly on

centralistic decision-making led

towards nationalism and

disintegration; as for

representatives of less developed

republics, this was all more about

existential than ideological issue.

They saw liberalization of the

economic policy, introduction of

market criteria in economic life

and, above all, the end of federal

subventions as insurmountable

obstacles to further development of

their societies. All this once again

revealed many lose ends of the

Yugoslav sociopolitical experiment.

Along with the existing

argumentation relations between

republics and interethnic relations

became main criteria for

decision-making throughout the

1960s. exactly became a crucial economic

and political problem in the

functioning of the Yugoslav

federation. “Developed regions,

those that made bigger progress,

must be lagging in the domain of

investment; otherwise, those that

are not made progress cannot develop

themselves,” he said in 1960, adding

that due to such policy Croatia had

been lagging behind less developed

republics for the past 15 years.10 In

Bakarić’s opinion – to be accepted

by the majority of the Croatian

leadership – the federation should

become much more flexible (to

different solutions), i.e. it should

“flex.”11 Motives of the opponents of

decentralization were different. For

some, loss of the monopoly on

centralistic decision-making led

towards nationalism and

disintegration; as for

representatives of less developed

republics, this was all more about

existential than ideological issue.

They saw liberalization of the

economic policy, introduction of

market criteria in economic life

and, above all, the end of federal

subventions as insurmountable

obstacles to further development of

their societies. All this once again

revealed many lose ends of the

Yugoslav sociopolitical experiment.

Along with the existing

argumentation relations between

republics and interethnic relations

became main criteria for

decision-making throughout the

1960s.

3. FLEXING THE FEDERATION

High – or, to put

it precisely, unrealistic –

expectations from the country’s

economic growth, along with

growingly evident shortcomings of

the existing system, brought about

(another) crisis in the early 1960s.

Deeper and deeper gap between theory

and practice of the Yugoslav system

of self-government remained a key

problem. Full implementation of

provisions of federal legislation

and wordings of party documents was

impossible “in the field.” The state

remained the most powerful subject

of economic policy. The attempt at a

mini-reform in 1961 failed. True,

for the first time since 1950 the

state permitted enterprises to

independently decide on the use of

their income – but that was mostly

the one and only achievement.12

According to

Branko Horvat, one of most renowned

Yugoslav economist of the time, the

reformist attempt failed for two

reasons. Firstly, political

opposition to further liberalization

of the economy (and society) was

growing. Secondly, nothing or almost

nothing was known about functioning

of a decentralized economy

mechanisms, which was why the reform

was neither properly prepared nor

implemented.13 After ten years of

permanent economic growth the new

crisis baffled many and even shaken

their belief. Doubts about the

rationale behind decentralization

and more radical function of market

mechanisms were more and more given

voice to. The dilemma – to stick to

the reformist course or resume the

old model – split economist and

Yugoslavia’s political leadership

alike. By their views on the role a

state should play in development of

a society, their split boiled down

to two camps: centralists and

decentralists. The former were also

labeled conservatives, bureaucrats

and dogmatists, while the latter –

liberals.14 As the time went by, this

heterogeneity was more and more

manifest. Antagonisms between

republics, peoples and generations

just fit in the existing ones.

Although opposing stands were more

and more evident it was hard to tell

at the beginning which of the two

opposing “camps” individual leaders

have belonged to.

The situation

culminated in 1962. In his opening

address to the session of the

Executive Committee of the CC of the

LCY on March 14-16, 1962, Tito said,

“In my opinion, this is not an

economic but a political crisis that

shakes our country…Just take a look,

comrades, at the atmosphere of the

meetings of the Federal Executive

Council!...Listen to the sound and

contents of the debates they engaged

in!...One often asks himself, ‘Well,

is that country of ours really

capable of holding on, not to

disintegrate?’”15 Quoting major

reasons behind the crisis Tito spoke

as a mouthpiece of the conservative

current. “What we are having now is

unconcern, party indiscipline,

cadres who are swept by the

avalanche of petty bourgeois, under

the influence of nationalistic and

chauvinistic circles, and

preoccupied with everyday work and

local interests while neglecting

basic interests of our whole

community. And, of course, we also

have disparities in economic

development and unfair competing in

investments, construction of various

uneconomic and other not exactly

necessary facilities that are costly

and insufficient solidarity among

the republics.”16 Speaking of

decentralization Yugoslavia’s Number

One concludes, “Some of our people

are more and more perceiving in

decentralization the character and

sense of disintegration.17 The same,

conservative tone marks one of

Tito’s best known speeches,

delivered in Split on May 6, 1962.18

Differences in

views about Yugoslavia’s future were

also bigger and bigger among

economic experts. Open conflicts

between them coincided with

conflicts in the political

leadership. Key issue debated at the

conference of the Alliance of

Economists of Yugoslavia, in

December 1962 in Belgrade, was

whether to prioritize market economy

or (social) planned. A month later

in Zagreb (January 17-19, 1963) an

even sharper discussion by same

participants ensued. This time the

opposing groupings presented two

documents (known as Yellow and White

Book) whereby each argued for its

economic models.19 The “Yellow Book”

composed in the Federal Bureau of

Planning, indentified the causes of

the crisis in poorly prepared and

implemented “liberal” reforms

(1961), and serious mistakes made in

the structure of investment. The

“White Book” was produced in Zagreb

at the initiative of Vladimir

Bakarić. Its authors were Croatia’s

leading economists, including Savka

Dabčević Kučar, Jakov Sirotković and

Ivo Perišin who would play more and

more important roles in the next

period. According to the three,

centralistic planning was useful in

the early stage of economic

development, but then became

extremely dysfunctional. Now, when

economic growth was at a much higher

level, the economy should function

more by market laws, and less by

interventions of “planners” or

politicians. Dennison Rusinow takes

that the “White Book” was the first

comprehensive document that signaled

the Croatian model for a developed

socialist state.20 documents (known as Yellow and White

Book) whereby each argued for its

economic models.19 The “Yellow Book”

composed in the Federal Bureau of

Planning, indentified the causes of

the crisis in poorly prepared and

implemented “liberal” reforms

(1961), and serious mistakes made in

the structure of investment. The

“White Book” was produced in Zagreb

at the initiative of Vladimir

Bakarić. Its authors were Croatia’s

leading economists, including Savka

Dabčević Kučar, Jakov Sirotković and

Ivo Perišin who would play more and

more important roles in the next

period. According to the three,

centralistic planning was useful in

the early stage of economic

development, but then became

extremely dysfunctional. Now, when

economic growth was at a much higher

level, the economy should function

more by market laws, and less by

interventions of “planners” or

politicians. Dennison Rusinow takes

that the “White Book” was the first

comprehensive document that signaled

the Croatian model for a developed

socialist state.20

Although the

crisis shaking the country and

criticism of the economic policy by

Yugoslavia’s leading economists

played into the hands of

“centralists” that was not enough to

generate a U-turn in governance.

Like in many other similar

situations Josip Broz Tito had a

final say. Despite between-the-lines

wavering in his earlier speeches

throughout 1962, as early as in July

of the same year, at the Fourth

Plenary Session of the CC of the LCY

he made no bones about his idea of

Yugoslavia’s future course. Having

warned of the growing

bureaucratization, he criticized

dogmatic centralism and once again

emphasized the crucial role of

decentralization: decentralization

of the state capital in favor of

direct producers in the first place.21

The choice he made signaled victory

of reformist forces and the

possibility for further improvements

in the existing system. This was the

atmosphere in which the Constitution

of the SFRY – also called the

Self-government Charter – was

declared (April 7, 1963) and the 8th

Congress of the LCY (December 7-13,

1964) held.22 Adoption of the

self-government idea – and almost

fifteen years of its inconsequent

implementation – Yugoslavia’s

economic and hence overall social

development found themselves in a

blind alley. The level of

development the country has reached

called for more active involvement

in global economic processes and

excluded fragmentary measures

compromising by character.

A package of

measures the Federal Assembly

adopted on July 24, 1965, implying

the most radical transformation of

the country’s economic system since

the beginning of self-government in

1950, was expected to solve the

problem. The economic reform of 1965

took into account all the lessons

learnt and set several main goals.23

It posited that further development

was possible only by having the

extensive production model replaced

by an intensive production one.24 Some

new measures were introduced in

addition to those ensuring continued

struggle against still omnipresent

elements of bureaucratic

centralization and creating

conditions for enterprises to

directly dispose of segments of

their accumulation and increased

reproduction. With a view to making

Yugoslavia as good as possible

player at the international market,

prices underwent correction (they

grew in this case) and customs

changed accordingly. Dinar was

devaluated vis-à-vis US dollar as a

prelude to changes in the domain of

foreign trade.25 Probably Dennison

Rusinow best described how

all-inclusive and extensive the

economic reform was. In his report

on Yugoslavia he called it, in order

to make it better understandable to

American readers, „laissez-faire

socialism“or „Adam Smith without

private capitalism“.26

This time,

however, it became evident at the

very beginning of the reform that

desired results would be much harder

to achieve than expected. Standards

of living suffered first since

citizens’ expenditures grew by 35%

due to overall price raise. The

state intervened: only two weeks

after the reform had been started it

decided to put an end to price raise

of services and commodities.27 Then

the newly introduced earnings system

began generating by far bigger and

more far-reaching problems.

Autonomous status of enterprises

implied noninterference in business

policies on the one hand, but the

end of governmental subventions on

the other. Majority of enterprises

were not prepared for such a

“liberal” U-turn. Chain reaction of

negative effects on enterprises and

individuals alike ensued. In fear of

unfavorable business conditions

enterprises decided against cuts in

material expenses and wages; instead

they decided to stop employing

people and then to fire workers.

According to a November 1965 survey,

425 enterprises employing 225

thousand people had already given

walking papers to 12,574 and planned

to let go another 19,000.28 For the

first time after 1945 the number of

working people either stagnated or

decreased. Apart from numerical

indicators the said process also had

a strong influence on the structure

of the employed. More and more of

young and highly educated people

were among the unemployed: they soon

went abroad in search of jobs. Like

other trends in economy functioning,

GNP rate became negative. While in

1957-64 GNP rate was 10.2%, in 1964

– 65 it spiraled down to 2.9%. The

rate of industrial production from

12.5% dropped to 8%.29

Though many

reformist politicians were also

disappointed with the initial

outcomes it never occurred to them

to intervene in the proposed

measures. On the contrary, this time

they opted for a showdown with

“brakemen” of changes to manifest

how strongly they believed in the

reformist course. As mentioned

above, the term “conservatives” had

already embed itself in political

vocabulary to denote all the

opponents to the reforms. As the

time went by the term was implying

much more than that. In terms of

generations it mostly referred to

“old” partisan cadres and staunch

communists to whom economic and

political decentralization meant

nothing by disintegration of the

country they had created in the war.

From intellectual angle the term was

reserved for poorly educated or

uneducated persons in high offices

in the administration and economy

alike. They were aware that their

positions were shakier and shakier

with the country’s further

modernization and integration into

global economic processes.30 In

regional terms, conservatives were

practically equally distributed

throughout Yugoslavia although

undeveloped republics were usually

quoted as “centers” of their

operation. Generally speaking, the

new economic and social reform was

seen as more beneficial to Slovenia

and Croatia, whereas other (less

developed) republics would have made

more progress in a centralized

state. However, generalization by

the principle “liberal” and

reformist Slovenians and Croats on

the one hand, and conservative

Serbs, Macedonians, Montenegrins and

Muslims on the other only further

antagonized relations between

Yugoslav peoples. In their analyses

of the situation in Yugoslavia it

was in this perception that some

identified a generator of

misunderstanding and even growingly

open conflicts between republics.

“Serb ‘conservatives’ tend to think

that pro-reform ‘liberals’ are all

Croats and Slovenes, favoring the

interests of their relatively

developed parts of the country; at

the same time, a terrifying weakness

of Croat ‘liberals’ is their common

failure to perceive that all Serbs,

etc., are not necessarily

‘conservative’ representatives of

economically and politically

underdeveloped regions.“31 Considering

all this, it is obvious that

opponents to the reform did not make

up an organized and homogeneous

grouping, but it is evident as well

that they had a considerable

influence on the process of

decision-making and implementation

of the reform. It was clear,

therefore, that would be impossible

to choke down each individual

“conservative.” It was decided

instead to open fire just on the

very center of the resistance and a

person considered as the one

standing behind dogmatic, Unitarian

and anti-reformist trends. The

situation was the more so

complicated since this was about the

untouchable and omnipotent UDB

(Department of State Security) and

its boss Aleksandar Ranković

considered Yugoslavia’s number two

for years. His deposal following the

Fourth Plenary Session of the CC of

the LCY (July 1, 1966) and ensuing

reorganization of the state security

service initiated a wave of

liberalization in all segments of

the society. In her memoirs Savka

Dabčević Kučar comments on the

situation after the Brioni Plenum

saying, “As if we were now breathing

more freely.”32 Although Ranković had

been ousted and intelligence

services thoroughly reformed

expectations that all centralist

elements would disappear in

Yugoslavia were unrealistic. These

elements had been defeated but yet

omnipresent in all segments of the

society, at all levels of power and

in all parts of the country.

However, decentralization –

political and economic – was

jeopardized or questioned no more.

Decentralization, regretfully, did

not mean complete abandonment of all

centralist tendencies. Instead of

the federal center the state was

more and more thorn by six

republican centralisms. Many

controversies and all economic,

national and social differences –

not necessarily factors of

instability per se – surfaced

against a backdrop as such. The

country’s biggest problem became

people supposed to be act as its

leaders. Political elite was

disunited and state interests were

more and more held down in favor of

republican. Power struggle, concern

for own problems and disregard of

the problems facing others justified

Tito’s fears that decentralization

could easily lead towards

disintegration. very center of the resistance and a

person considered as the one

standing behind dogmatic, Unitarian

and anti-reformist trends. The

situation was the more so

complicated since this was about the

untouchable and omnipotent UDB

(Department of State Security) and

its boss Aleksandar Ranković

considered Yugoslavia’s number two

for years. His deposal following the

Fourth Plenary Session of the CC of

the LCY (July 1, 1966) and ensuing

reorganization of the state security

service initiated a wave of

liberalization in all segments of

the society. In her memoirs Savka

Dabčević Kučar comments on the

situation after the Brioni Plenum

saying, “As if we were now breathing

more freely.”32 Although Ranković had

been ousted and intelligence

services thoroughly reformed

expectations that all centralist

elements would disappear in

Yugoslavia were unrealistic. These

elements had been defeated but yet

omnipresent in all segments of the

society, at all levels of power and

in all parts of the country.

However, decentralization –

political and economic – was

jeopardized or questioned no more.

Decentralization, regretfully, did

not mean complete abandonment of all

centralist tendencies. Instead of

the federal center the state was

more and more thorn by six

republican centralisms. Many

controversies and all economic,

national and social differences –

not necessarily factors of

instability per se – surfaced

against a backdrop as such. The

country’s biggest problem became

people supposed to be act as its

leaders. Political elite was

disunited and state interests were

more and more held down in favor of

republican. Power struggle, concern

for own problems and disregard of

the problems facing others justified

Tito’s fears that decentralization

could easily lead towards

disintegration.

In the late 1960s

decision-makers – apart from

know-how - were more and more split

by regional, i.e. republican “key.”

Decentralization of economic policy

and introduction of the laws of free

market further emphasized

differences between Yugoslavia’s

developed and underdeveloped

republics. Unlike subventions that

often turned unprofitable, the

struggle for more favorable

investment and loans deepened

rivalry between enterprises

throughout Yugoslavia. The novelty

was banks replaced the state as key

players of financing and lending.

Banks were first of all other

economic factors that adjusted

themselves to market economy. To

them, profit was crucial rather than

interests of the country’s economy.

Accordingly, the new investment and

credit policy favored successful and

profit-making enterprises while

neglecting those that failed to find

their way in new circumstances.

Fully justified from a capitalist

point of view, in a socialist

society this was diametrically

opposite to initial wishes; and the

more so since most capital began

concentrating again in one place –

this time not in the federal

treasury but in several most

powerful central banks.

The state did

transfer some of its rights and

duties to the banking system but

still kept to itself the right to

participate in investment programs

though the so-called non-budget

balance of payment. By its own

criteria it continued financing (old

and new) project with these funds.

And those criteria, often

politically rather than economically

motivated, were factors that further

sharpened republics between

republics. Along with funds that

survived (such as the Fund for

Speedier Development of Less

Developed Regions) the moneys from

non-budget balance of payment were

straws to clutch at for all those

unable to produce good results on

their own. Reciprocity of this form

of solidarity was questioned as

crucial to further functioning of

the federation on equal footing.

Given that development of each and

every sociopolitical community

(municipality, province or republic)

was in reciprocal relationship with

economic results on its territory

competition in economic sphere moved

to political as well. In a socialist

state with a strong monopoly of one

party a specific federal system was

in causal relation with economic,

political and social problems.

Stable and even prosperous economic

situation in earlier periods

guaranteed social and political

peace. On the other hand, economic

crisis that started shaking the

Yugoslav society following the

economic reform in 1965 threatened

with turning into an open political

crisis with far-reaching

consequences. This is why solving of

accumulated economic problems had to

be placed at the priority list of

politics. Unfortunately, political

elite and economic experts mostly

failed to meet the criteria

necessary for pulling the country

out of crisis.

The wave of

student protests that swept over

almost all Yugoslav universities in

the first week of June 1968 was only

one of many signs warning that the

country was in a deep crisis. In

general public the crisis was being

mostly perceived through its

economic consequences (the fall in

living standard, growing

unemployment, etc.). However, the

economic crisis was in causal

relation with its deeper and deeper

political counterpart. Though not so

much visible to most citizens, and

especially not in its full intensity

and all of its forms, its escalation

threatened even the very survival of

the federation. The political crisis

was by far more dangerous than

negative trends in the economy. The

model (s) of the federation’s

functioning, economic and political

position of republics undergoing

economic and social reforms, and

relations between the “developed”

and “underdeveloped” were just some

of the issues highest officials were

growingly unable to reach consensus

on. Despite all the attempts to

resort to Aesopian hints so as to

assuage the crisis among the general

public, stormy meetings behind

closed doors indicated overt

antagonisms between individuals and

even the entire republican

leaderships. One of such meetings

was that of the Presidency of the EC

of LCY, chaired by Tito, held on

June 9, 1968. Members of the Serbian

leadership used the debate on

successes and failures of the

economic reform to complain against

their Zagreb colleagues. They

accused the Croatian leadership,

especially Mika Tripalo, of

undermining the principle of

democratic centralism by publicly

criticizing the federal bodies’

stands. They mostly referred to the

so-called May Consultations of the

CC of LCC (May 28-29, 1968) and

interviews some of Croatian leaders

gave to the media after it. Serbian

politician Dobrivoje (Bobi)

Radosavljević reproached the Croats

for openly accusing the Serbs of

still building unprofitable plants.

Some of them, he said, are important

for political rather than economic

reasons, but the problematic should

be nevertheless considered against a

larger economic-political background

and in a long run. “We are ready to

discontinue construction of every

facility,” he argued, adding

“However, we in Serbia are

hypothecated by old relations, by

the compromise between republican

leadership and these facilities are

a hypothecation of that compromise.”33

The problem of the so-called

political facilities was not the

only one, it was used just as a

paradigm. Critical remarks were also

about the Croatian leadership’s

practice of open polemics all other

problems of the economic reform,

such as the federation’s balance

sheet and foreign exchange regime.

He especially criticized the Croats

for using Tito as “a shelter” much

too often. “Comrade Tito, as we have

said on hundreds occasions, belongs

to all Yugoslav people, he

personifies our revolution and our

attainments…Comrades from Croatia

have to solve everything they

disagree with through dialogues with

other republics so that we find

mutual solutions in debates. One

cannot go to Tito to settle the

matters,” he warned.34 Representatives

from Montenegro (Đoko Pajković) and

Bosnia-Herzegovina (Rato Dugonjić)

sided with the Serbian leadership.

However, they criticized the methods

used by the Croatian leadership more

than what the latter had actually

said. Responding to all this, Savka

Dabčević-Kučar, minutely elaborated

the stances on (non)implementation

of economic reform taken by the

Croatian leadership. He pointed to

crumbling economy, inconsequent

foreign trade and foreign exchange

regimes, non-existence of clear-cut

and transparent accounts such as the

federation’s balance sheets, etc. To

end with, she said that in her

opinion speaking publicly about the

stances voted in by the Croatian

Assembly and Executive Committee

that were contrary to the decisions

taken by federal institutions were

not political subversion. This meant

not disagreement with the majority

or disrespect of democratic

centralism, she said, but an

obligation towards citizens of one’s

republic, the more so since after

each meeting of the Federal

Executive Council /SIV/ a brief

about a consensus reached on

decisions made was being issued.

Following her lengthy discussion

that clearly indicated many problems

undermining not only economic reform

but also federal relations, no one

denied her critical remarks.

Dobrivoje Radosavljević and Rato

Dugonjić just repeated their

criticism of going public. “In my

view, one should go public but

should first think twice when and

how, and try to settle everything

among leaderships,” said the Serbian

delegate while his counterpart from

Bosnia-Herzegovina wondered, “Can

one political leadership problem one

policy and fight for it without

having discussed in here first?”35

Neither of the two pointed a finger

at what was actually mistaken in the

policy proclaimed by the Croatian

leadership. This provoked Mika

Tripalo’s comment on the whole

discussion. “We haven’t heard any

argument that would deny some of our

basic political stands…I do not

claim that we are right about

everything we are saying, but let’s

then discuss contents, not methods.”36

Two statements by Jakov Blaževića

further sharpened the debate. He

first said that assaults at Tripalo

were in fact screened assaults

against the economic reform and Tito

in person.37 This provoked Petar

Stambolić to call for the

Presidency’s and EC CC LCY’s

distancing themselves from

Blažević’s statements as untrue.

Blažević’s second statement,

actually his rhetorical question

about how come that hotbeds of

crisis had not been identified, as

well as the people responsible for

student protests if the latter had

been known for years. Members of the

Serbian leadership realized that

they were actually on the carpet

list. Radosavljević said to Blažević

nervously, “Why don’t you, comrade

Jakov, come to Belgrade to govern,

as you are capable of assessing

everything? But you are sitting in

Zagreb and reading papers, and

conclude that the CC leadership is

opportunistic. None of us should be

just sitting here, so come on and

govern!”38 Petar Stambolić followed in

his footsteps in the same tone; he

criticized Blažević of not having

taken into consideration documents

of Serbia’s Presidency and EC of CC

of LCS while assessing the situation

but only statements given by some

individual leaders. He also

reproached the entire Croatian

leadership: at the moment student

protest broke out Zagreb enquired

whether demonstrations were

pro-Ranković or progressive. On the

basis of the official stance that

the protest was against the regime,

Stambolić drew the conclusion that

the enquiry suggested that the

Serbian leadership was seen as

conservative and, therefore,

protests against it could be either

pro-Ranković or progressive.39 As said

above, over this Croatian-Serbian

polemics Bosnian and Montenegrin

representatives made no bones about

what they agreed and what disagreed

with. Macedonian representative

Krste Crvenkovski tried to position

himself as an impartial observer

aware of failures of both sides but

appealing for unity in the interest

of the progress of the whole

country. The stance taken by

Slovenian representative France

Popit was more clear-cut. The same

as the Croatian leadership he

criticized elements of centralism

still visible in functioning of the

federal administration, and

emphasized the necessity placing

many powers from federal to

republican level. His motivation,

however, was not to provide support

to the Croatian leadership but to

advocate the interests that would

benefit his own republic. Sharp

statements heard at this meeting

indicated that cohesion of

Yugoslavia’s top political

leadership was considerably

undermined. More and more often,

like at this meeting, it was only

Josip Broz Tito’s authority that

could put an end to mutual

allegations and accusations. Apart

from documents, impressions by many

of those involved also indicate to

seriousness of the situation. In her

memoirs Savka Dabčević Kučar writes

about her flight on the way to this

meeting. While her plane was nearing

Belgrade a military aircraft

intercepted the plane so closely

that it lost altitude and its pilot

hit his head on the cabin’s roof.

Considering that never before had

military aircrafts “welcomed” planes

taking politicians to meetings, she

writes, “Have they, probably, wanted

to get rid of all of us, at once and

just by ‘chance’?”40 obligation towards citizens of one’s

republic, the more so since after

each meeting of the Federal

Executive Council /SIV/ a brief

about a consensus reached on

decisions made was being issued.

Following her lengthy discussion

that clearly indicated many problems

undermining not only economic reform

but also federal relations, no one

denied her critical remarks.

Dobrivoje Radosavljević and Rato

Dugonjić just repeated their

criticism of going public. “In my

view, one should go public but

should first think twice when and

how, and try to settle everything

among leaderships,” said the Serbian

delegate while his counterpart from

Bosnia-Herzegovina wondered, “Can

one political leadership problem one

policy and fight for it without

having discussed in here first?”35

Neither of the two pointed a finger

at what was actually mistaken in the

policy proclaimed by the Croatian

leadership. This provoked Mika

Tripalo’s comment on the whole

discussion. “We haven’t heard any

argument that would deny some of our

basic political stands…I do not

claim that we are right about

everything we are saying, but let’s

then discuss contents, not methods.”36

Two statements by Jakov Blaževića

further sharpened the debate. He

first said that assaults at Tripalo

were in fact screened assaults

against the economic reform and Tito

in person.37 This provoked Petar

Stambolić to call for the

Presidency’s and EC CC LCY’s

distancing themselves from

Blažević’s statements as untrue.

Blažević’s second statement,

actually his rhetorical question

about how come that hotbeds of

crisis had not been identified, as

well as the people responsible for

student protests if the latter had

been known for years. Members of the

Serbian leadership realized that

they were actually on the carpet

list. Radosavljević said to Blažević

nervously, “Why don’t you, comrade

Jakov, come to Belgrade to govern,

as you are capable of assessing

everything? But you are sitting in

Zagreb and reading papers, and

conclude that the CC leadership is

opportunistic. None of us should be

just sitting here, so come on and

govern!”38 Petar Stambolić followed in

his footsteps in the same tone; he

criticized Blažević of not having

taken into consideration documents

of Serbia’s Presidency and EC of CC

of LCS while assessing the situation

but only statements given by some

individual leaders. He also

reproached the entire Croatian

leadership: at the moment student

protest broke out Zagreb enquired

whether demonstrations were

pro-Ranković or progressive. On the

basis of the official stance that

the protest was against the regime,

Stambolić drew the conclusion that

the enquiry suggested that the

Serbian leadership was seen as

conservative and, therefore,

protests against it could be either

pro-Ranković or progressive.39 As said

above, over this Croatian-Serbian

polemics Bosnian and Montenegrin

representatives made no bones about

what they agreed and what disagreed

with. Macedonian representative

Krste Crvenkovski tried to position

himself as an impartial observer

aware of failures of both sides but

appealing for unity in the interest

of the progress of the whole

country. The stance taken by

Slovenian representative France

Popit was more clear-cut. The same

as the Croatian leadership he

criticized elements of centralism

still visible in functioning of the

federal administration, and

emphasized the necessity placing

many powers from federal to

republican level. His motivation,

however, was not to provide support

to the Croatian leadership but to

advocate the interests that would

benefit his own republic. Sharp

statements heard at this meeting

indicated that cohesion of

Yugoslavia’s top political

leadership was considerably

undermined. More and more often,

like at this meeting, it was only

Josip Broz Tito’s authority that

could put an end to mutual

allegations and accusations. Apart

from documents, impressions by many

of those involved also indicate to

seriousness of the situation. In her

memoirs Savka Dabčević Kučar writes

about her flight on the way to this

meeting. While her plane was nearing

Belgrade a military aircraft

intercepted the plane so closely

that it lost altitude and its pilot

hit his head on the cabin’s roof.

Considering that never before had

military aircrafts “welcomed” planes

taking politicians to meetings, she

writes, “Have they, probably, wanted

to get rid of all of us, at once and

just by ‘chance’?”40

Antagonism between

Croatian and Serbian leaderships was

by far more complex than a

misunderstanding over one statement.

The problem was in their differing

perception of the goals of the

economic reform and, hence, in their

different understanding of

republics’ economic-political

standing within the federation.

Comments on the federation’s balance

sheets made by two of Serbia’s top

brass politicians best illustrate

these fundamental differences. While

transparent accounts were for Zagreb

condition sine qua not of the

federation’s sustainability and

guarantees of equality of its

constitutive parts, what bothered

Dobrivoje Radosavljević was that the

Croats were “carping on the issue

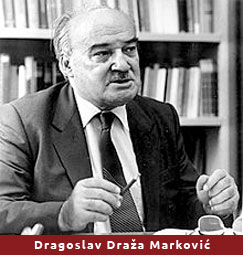

for months.”41 Draža Marković also

voiced his disagreement with

Croatian requests. He wrote in his

diary on May 17, 1968, “The

situation of balance sheets

(relations with the Croats, in fact)

is turning more and more

complicated. However, it’s good that

they remained isolated and will

surely have to withdraw.”42 Marković

was only partially right. The Croats

did remain alone since their

requests were outvoted in federal

institutions. On the other hand, he

was not exactly right in his

argument about their withdrawal. In

the line with democratic centralism

the Croats acknowledged the majority

vote but decided to take a step that

would cause the above-mentioned

stormy reactions. This time

frustration with the decision-making

procedure in Belgrade, especially

with the quality of these decisions,

spread beyond the small circle of

top leaders. Having realized that

support could not be obtained from

politicians the leadership of the SR

of Croatia turned to the general

public. these fundamental differences. While

transparent accounts were for Zagreb

condition sine qua not of the

federation’s sustainability and

guarantees of equality of its

constitutive parts, what bothered

Dobrivoje Radosavljević was that the

Croats were “carping on the issue

for months.”41 Draža Marković also

voiced his disagreement with

Croatian requests. He wrote in his

diary on May 17, 1968, “The

situation of balance sheets

(relations with the Croats, in fact)

is turning more and more

complicated. However, it’s good that

they remained isolated and will

surely have to withdraw.”42 Marković

was only partially right. The Croats

did remain alone since their

requests were outvoted in federal

institutions. On the other hand, he

was not exactly right in his

argument about their withdrawal. In

the line with democratic centralism

the Croats acknowledged the majority

vote but decided to take a step that

would cause the above-mentioned

stormy reactions. This time

frustration with the decision-making

procedure in Belgrade, especially

with the quality of these decisions,

spread beyond the small circle of

top leaders. Having realized that

support could not be obtained from

politicians the leadership of the SR

of Croatia turned to the general

public.

In late May 1968

(28-29) the EC of the CC of LCC

initiated consultations in Zagreb

(May Consultation) with

participation of political leaders

from all over Croatia. Though

presented as one in a row of

pre-congress debates the

consultation was mostly used for

informing the public about the

stands the Croatian leadership

considered incorrectly outvoted at

the federal level. In his address

Secretary of the EC Mika Tripalo

stressed out imperative disburdening

of the economy, which would make it

possible for working organizations

to operate more freely, enable

investment in modernization and

ensure higher salaries. Otherwise,

working organizations’ insolvency

would strengthen the monopoly of new

centers of economic power such as

banks and foreign trade or re-export

enterprises.43 Notwithstanding all

objectively aggravating

circumstances one of most

influential factors slowing down the

economic reform was the very League

of Communists, said Tripalo. “Devoid

of clear-cut prospects the League of

Communists manifests ideological

confusion as some of its highest

bodies are paralyzed,” said Tripalo.44

This was not for the first time that

he warned his colleagues that

settling the situation of their own

ranks preconditioned reformist

tendencies in the society.45 However,

this time he argued for a public

debate on the newly emerged problems

since the political leadership had

not found a solution to them.

“Saying that the debate has to be

public means not an open debate

within the party but the debate

involving the whole society, which

is the only way for truly socialist

and progressive forces to win out…A

discussion in forums behind closed

doors fundamentally hinders

attainment of that goal and leaves

negative political and social

side-effects on our country.”46 To end

with he stressed that consequent

implementation of the economic

reform implied certain changes in

the political system. This primarily

referred to a change in the

relationship between the federation

and republics, but also to further

improvements in inter-republic and

interethnic relations. In order to

make self-governing relations

stronger at all levels, said

Tripalo, the Croatian leadership

takes that many activities federal

institutions were implementing could

be transferred to self-governing

bodies and their administrative

divisions in republics and communes.

In response to the arguments that

suggestions as such were undermining

Yugoslavia, he said, “Yugoslavia is

not strengthened only by the federal

centre but by all its parts, and on

the basis of full equality of all

nations and their mutual

cooperation.”47 Although Tripalo’s

address already hinted true reasons

for convening the May consultation

meeting the very announcement that

Savka Dabčević-Kučar would address

it removed doubt. The Member of the

Presidency of CC of LCY and

President of the Republican

Executive Council was asked to

provide a more precise explanation

of the SIV press release saying that

all the republics had reached a

consensus on the federation’s

balance sheet on the one hand, and

the Croatian leadership’s well-known

opposite stand about the matter on

the other.48 The main problem, said

Dabčević-Kučar, was absence of

precise quantification of indicators

of the plan’s implementation and

non-implementation, which

preconditioned objective assessment

of results of the economic reform.

This was why the Croatian leadership

had asked to see the complete

balance sheet of the federation,

which implied the federal budget,

non-budget balance sheet, the

balance sheet of the General

Investment Fund, as well as the

balance sheet of foreign economic

relations. It turned out, however,

that authorized bodies had no system

for monitoring and registering

accounts that would have make it

possible to determine the exact

state of affairs in individual

sectors. Consequently, assessment of

the progress made and the plan for

the steps to be taken was brimming

with contradictions.49 At the SIV

session of May 17, 1968

representatives of other republics

had not accept critical remarks by

the Croatian leadership calling them

superfluous, and measures suggested

by the SIV sufficient for correction

of negative trends in 1967. Without

questioning the majority will

Dabčević-Kučar nevertheless warned

that the public was entitled to be

informed about Croatian stands as

well. The May Consultation was held

ten days later. bodies and their administrative

divisions in republics and communes.

In response to the arguments that

suggestions as such were undermining

Yugoslavia, he said, “Yugoslavia is

not strengthened only by the federal

centre but by all its parts, and on

the basis of full equality of all

nations and their mutual

cooperation.”47 Although Tripalo’s

address already hinted true reasons

for convening the May consultation

meeting the very announcement that

Savka Dabčević-Kučar would address

it removed doubt. The Member of the

Presidency of CC of LCY and

President of the Republican

Executive Council was asked to

provide a more precise explanation

of the SIV press release saying that

all the republics had reached a

consensus on the federation’s

balance sheet on the one hand, and

the Croatian leadership’s well-known

opposite stand about the matter on

the other.48 The main problem, said

Dabčević-Kučar, was absence of

precise quantification of indicators

of the plan’s implementation and

non-implementation, which

preconditioned objective assessment

of results of the economic reform.

This was why the Croatian leadership

had asked to see the complete

balance sheet of the federation,

which implied the federal budget,

non-budget balance sheet, the

balance sheet of the General

Investment Fund, as well as the

balance sheet of foreign economic

relations. It turned out, however,

that authorized bodies had no system

for monitoring and registering

accounts that would have make it

possible to determine the exact

state of affairs in individual

sectors. Consequently, assessment of

the progress made and the plan for

the steps to be taken was brimming

with contradictions.49 At the SIV

session of May 17, 1968

representatives of other republics

had not accept critical remarks by

the Croatian leadership calling them

superfluous, and measures suggested

by the SIV sufficient for correction

of negative trends in 1967. Without

questioning the majority will

Dabčević-Kučar nevertheless warned

that the public was entitled to be

informed about Croatian stands as

well. The May Consultation was held

ten days later.

Although Serbian

politicians criticized their

Croatian colleagues the most saying

that it was solely about

Croatian-Serbian dispute would be

absurd and untrue. Anyway, the 5:1

ratio in major decision-making

clearly denies such a thesis. It

should be said that the said ratio

was mostly manifest when it came to

measures taken in economic policy

since the reasons behind them were

diametrically opposite to those for

taking political. In economic

matters too big differences in the

level of economic development

between Yugoslav republics and

provinces were decisive factors.

Slovenia, Croatia and Province of

Vojvodina were by many criteria

above the Yugoslav average, Serbia

without provinces was in the mean,

while Montenegro,

Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia and

Province of Kosovo below the

average.

Such

constellation, to start with,

hindered a homogeneous approach to

resolution the country’s economic

problems. Before and even more after

the beginning of economic reforms

the underdeveloped had not been

capable of developing their

societies with their own funds and

resources. Therefore and despite a

general advocacy for political and

economic decentralization they had

still been vitally interested in

receiving funds from various federal

sources. Whether or not all deals

and transactions in the process were

fully transparent and economically

justified did not matter much to

them. On the other hand, the

developed saw the measures of

economic reforms and, especially,

decentralization as opportunities

for making even speedier progress.

The attempts at having the accounts

settled or the necessity to have the

state of accounts determined in

detail, and then also the modalities

for the use of mutual funds were

stroke the eye eve more against a

backdrop as such. All this did not

question further assistance to

underdeveloped regions; on the

contrary, Croatian politicians and

economists were proposing even more

funds to them, but this time through

instruments that would not be

contrary to reformist principles.50

Apart from leaderships of

underdeveloped republics the Croats

also perceived the federal

bureaucracy – above all SIV and

various departments and commissions

of the Federal Assembly – as major

straitjackets of the economic

reform.51 Overt disagreement with the

decisions by the highest executive

body was even more manifest in early

1968, at the above-mentioned

parliamentary debate on the

Resolution on the Principles of

Economic Policy in 1968. Although

they had managed to have the

decision on limiting contribution

rates annulled by then, their

dissatisfaction with functioning of

the federal administration remained

evident. Kiro Gligorov, the

vice-president of the Yugoslav

government and one of politicians

with biggest influence on shaping

the country’s economic policy, was

seen as ‘drum major’ of

anti-reformist forces. The meeting

of the closest circle of Croatian

politicians of April 6, 1968

provides a most illustrative

instance of the extent of animosity

for this Macedonian leader. A debate

on the state of affairs at Yugoslav

universities unavoidable led to a

debate on successes/failures of the

economic reform. In this context

Kiro Glogorov was mentioned as one

of most responsible individuals.

“The entire group assembled around

Kiro is a gang that should be chased

away,” argued Vladimir Bakarić to

what Mika Tripalo added, “Including

him in person although he somewhat

stands for the reform.”52 No one

obviously denied that Glogorov was

the one who introduced the economic

reform but, as time went by, people

became skeptical about the way he

was trying to put theory into

practice. Probably neither was the

fact that Kiro Gligorov represented

one of most underdeveloped Yugoslav

republics, which could have barely

benefited from consequent

implementation of reformist measures

overlooked. Savka Dabčević Kučar

carried the argument a step further:

she connected criticism of Gligorov

with his favoring of the solutions

proposed by Serbia.53 The fact that

Croat Mika Špiljak acted as the

president of the Yugoslav government

in 1968 further complicated rather

undermined relations between the

Croatian leadership and federal

institutions. Thorn between his

republic’s expectations and the

actual power balance in the

federation he more often than not

gave the upper hand to the latter in

decision-making. So he did in the

case of the federation’s balance

sheet. After many meeting at which

Croat stands were mostly outvoted,

in early summer of 1968, at

Špiljak’s request the Federal

Assembly gave a vote of confidence

to the SIV and, by doing it,

according to Tripalo, adopted the

untrue balance sheet of the

federation.54 Tito considerably

contributed to such denouement: he

wanted to lessen inter-republican

tensions and so put an end to the

debate on the balance sheet, calling

the latter “a problem of secondary

character.”55

The country’s bad

economic situation opened up yet

another “front” for competing

republics. Debates on which of them

scored worst in Yugoslavia’s overall

economic development intensified.

Since everyone documented his thesis

with statistical data, Stipe Šuvar

commented on the new situation

saying, “Inter-republican and

interethnic accounting is blooming,

while everyone presents the data

that suits him and gives voice to

his own version of the truth, which

he serves to his national community

often by using refined or else

underhand methods.”56 Indicatively,

not a single republic was satisfied

with the level and speed of its

economic growth; each saw itself as

deprived of this or that when

compared with the rest. Developed

republics were trying to prove that

their economic stagnation was in

discord with their potentials and

opportunities for development. Major

critical remarks were that

disproportionately large funds were

flowing from Ljubljana and Zagreb

into federal funds and that these

funds were irrationally distributed

to underdeveloped regions. The

monopoly of foreign export companies

and the so-called federal banks was

especially on the carpet list – they

were accused of having taken over

from the state “the role of an

expropriator of the surplus of

labor” from producers.57 On the other

hand, the underdeveloped complained

of economic position within the

federation. According to them, they

were the ones taken advantage of.

First, as they are sources of raw

materials that are then used by

industries of developed republics

under favorable conditions, and then

turned into markets for the

developed to sale their tariff-free

products, they argued.58 The measures

of economic reforms further

intensified the existing

contradictions in socioeconomic

relations, which, in turn, triggered

off open debates on equality of

Yugoslav republics and nations.

Though “defense of self-government”

was still quoted from political

rostrums as a main reason for

correction of disparities, the

thesis about defense of national

interests was spreading in the

public life. This was especially the

case in developed republics. So, for

instance, during student protests in

1968 Slovenian students and

politicians were stressing further

development of the system of higher

education as “a vital, national

problem” given that “unbearable

situation of education threatens

Slovenia’s development.”59 with the level and speed of its

economic growth; each saw itself as

deprived of this or that when

compared with the rest. Developed

republics were trying to prove that

their economic stagnation was in

discord with their potentials and

opportunities for development. Major

critical remarks were that

disproportionately large funds were

flowing from Ljubljana and Zagreb

into federal funds and that these

funds were irrationally distributed

to underdeveloped regions. The

monopoly of foreign export companies

and the so-called federal banks was

especially on the carpet list – they

were accused of having taken over

from the state “the role of an

expropriator of the surplus of

labor” from producers.57 On the other

hand, the underdeveloped complained

of economic position within the

federation. According to them, they

were the ones taken advantage of.

First, as they are sources of raw

materials that are then used by

industries of developed republics

under favorable conditions, and then

turned into markets for the

developed to sale their tariff-free

products, they argued.58 The measures

of economic reforms further

intensified the existing

contradictions in socioeconomic

relations, which, in turn, triggered

off open debates on equality of

Yugoslav republics and nations.

Though “defense of self-government”

was still quoted from political

rostrums as a main reason for

correction of disparities, the

thesis about defense of national

interests was spreading in the

public life. This was especially the

case in developed republics. So, for

instance, during student protests in

1968 Slovenian students and

politicians were stressing further

development of the system of higher

education as “a vital, national

problem” given that “unbearable

situation of education threatens

Slovenia’s development.”59

Several months

before the Belgrade-seated NIN

magazine published a summarized

version of the article President of

the Executive Council of SR of

Slovenia Stane Kavčič had written

for Theory and Practice (Teorija in

praksa) magazine. Referring to the

necessity for revaluation of the

roles of Yugoslav republics within

the federation he writes among other

things, “I would say that we, the

Slovenes, also have to think about

statehood – but, of course, the

statehood that would imply a modern,

organized society rather than be a

synonym for bureaucracy.” He argues

against the so-called federation of

communes – with its too many and

poorly mutually connected communes –

with the thesis about republics as

nation-states being more influential

within Yugoslavia. “In fact, this is

all about realization that some

issues concerning an entire nation

had to be settled in alliance with

others, and fight against such

localism that is irrational and

harmful to the nation as a whole. If

we have acknowledged nations and are

aware that they would be there for

long time to come, then we also have

to acknowledge that there could be

no state without a nation or

nations, and that those nations

cannot be indifferent to their own

surplus of labor…All this logically

implies that each republic has to be

provided bigger economic

competences.”60

4. ANOTHER REFORM OF THE

CONSTITUTION AND THE PARTY

Shortly after

initial measures of the economic

reform were implemented it became

evident that the SFRY Constitution

had to undergo changes: some

provisions of the federal

constitution were incompatible with

the tendency of intensive

decentralization of the society. The

process of building of a new

political and legal frame that would

enable attainment of the expected

objectives and results of the

economic reform in the interest of

all nations and national minorities,

and hence of the entire federation,

was launched. In April 1967 the

federal parliament adopted a package

of six initial constitutional

amendments.61 Though the contents of

these amendments were considerably

changed already next year, their

purpose was obvious: to “weaken” the

federation and strengthen

federalism. Instead of the Federal

Chamber all major powers were

invested in the Chamber of Peoples,

which further strengthened position

of constitutive elements of the