|

Case

study

1

Abstract

This

article addresses manifestations of

Yugoslavism in the pre-1914 period

that have been neglected by recent

scholarship. Its focus on everyday

life reveals that since the

mid-1890s there were constant

contacts between the major ethnic

groups that would constitute

Yugoslavia after 1918. These

contacts were not initiated by the

political elite or by official

activities. They were instead the

reactions of ordinary residents of

Belgrade who “discovered” peoples

speaking the same language and

having similar problems, “as we do.”

There were many visits from

Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia to

Belgrade in the period 1890–1914

organized by different associations

or individuals. Some of them

organized public gatherings in the

center of Belgrade that allowed

residents to show “their love” to

“our compatriots” from the South

Slav lands of Austria-Hungary. Some

of these events turned into real

public demonstrations even before

1903, under an Obrenović dynasty and

government, which was not Yugoslav

oriented. And under the succeeding

Karađorđević dynasty, even its

leading Radical politicians favored

the Yugoslav idea for a future

state, although withholding public

support until after the Serbian

victory in the First Balkan War in

1912.

Key Words

Private

and public Yugoslavism, popular

culture, theatres, tourism

Yugoslavism is one

of the “unfortunate” subjects in

Serbian historiography, its

scholarly treatment too often

determined by political

considerations. During key periods

of the two Yugoslavias, Yugoslavism

became the official ideology, its

study obligatory and its roots

traced back as a scholarly inquiry.

Serbian historians delved as far

back into the past as the

Enlightenment (Ekmečić 1989: 3).

Whether serving the unification in

1918, the royal dictatorship of the

1930s, or the initial Communist

ideology, the common ethnic origins

of South Slav language and culture

were reference points on which the

intellectual as well as the

political elite constructed a set of

common national guidelines,

projects, and programs.

Once the second

Yugoslavia had disintegrated,

however, the denial of any such

prehistory began. Even primary

school textbooks featured sentences

like “the notion of Yugoslavism was

not widespread in Serbia into the

early 20th century” (Gaćeša,

Mladenović-Maksimović, and

Maksimović 1993: 49). Yugoslav

projects or programs were no longer

even mentioned but for the few that

could hardly be erased. Yugoslavia

itself was simply declared to have

been a political mistake (Rusinow

1990–91: 3). The bloody breakup of

Yugoslavia allowed many historians

to replace the earlier generation of

its advocates, becoming prosecutors

or judges of their former country,

although taking no responsibility

for its failings. Now we need to

return to the subject, nearly a

century since the first Yugoslavia

was created and the attendant

centenary scholarship joins in

reducing its founding to an

unfortunate consequence of the First

World War and the dissolution of

multiethnic empires now held in

newfound esteem. This positive

reappraisal of the Habsburg and

Ottoman Empires has fed off the

violence and ethnic cleansing of the

1990s. In the process it was easy to

forget that the Yugoslav idea was

more than 100 years old when the

country was first created in 1918

(Djokić 2003: 14). It is precisely

this long history and the

controversy surrounding the idea,

largely but not entirely shorn of

its initial inclusion of Bulgarians

after 1900, which are crucial to

understanding why the country was

twice created and twice destroyed.

The idea’s attraction that led to

the creation of two Yugoslavias and

two states which fell short of its

promise remain relevant to the

continuing social, economic, and

political problems of the

successors.

Revisiting Yugoslavism is important

not just because it has been

forgotten in the past 25 years. It

also affords us the chance to take a

fresh approach that reflects the

recent rise of cultural and social

history in providing insights beyond

the framework of traditional

political and economic history. That

is why the title of this article

addresses “everyday Yugoslavism” as

experienced by the Belgrade public

in the decades before the First

World War. Discoverable are signs of

ordinary people from Serbia

connecting primarily with Slovenes,

Croats, and vaguely defined Bosnians

and the ways in which they perceived

the idea of a Yugoslav community

before it became realistically

possible. Without official programs

for accepting Yugoslavism or

sponsorship by the ruling political

party, a process of mutual

introduction was taking place,

informal connections with people who

spoke a mutually comprehensible,

maybe even the same language. Under

an increasingly resented Habsburg

hegemony even before the Balkan Wars

of 1912–13, they felt the same

national frustration as Serbians

surrounded by large, hostile

empires.

Our subject is what John Lampe

called a change that was felt in the

atmosphere from the time when the

word “Yugoslav” entered the language

and came into everyday use (Lempi

2004: 63). This inquiry seeks to

capture that mood, to get a sense of

the milieu of ordinary people’s

thoughts and emotions. The main

sources are snapshots of events in

Belgrade, different cultural

activities that left their mark on

life in the capital and reflected

deeper political ideas and

processes. These occasions come from

theatre, concerts, sporting events,

and tourism. Together they fall

under the rubric of popular culture,

a relatively recent phenomenon which

democratized the political space by

giving voice to all members of

society. The analysis of these new,

modern spheres of urban life is

particularly important because it

shows that Yugoslavism existed not

only in the minds of certain

intellectuals and precious few

political leaders but that it

trickled down into the streets and

squares and spread from there. Here

in Belgrade was a population

newcomers, growing past 80,000 and

over two-thirds literate, a mixture

of students and state officials,

merchants and professionals, as well

as servants and day laborers. This

initial study of the phenomenon is

based on the new tabloid press of

the period. Our source is Večernje

novosti, chosen not only because of

its larger circulation than the

other tabloids but also because of

its political reputation as

conservative and anti-Yugoslav. Its

coverage nonetheless concentrated on

the atmosphere in the Belgrade

streets, reporting everyday events

without much comment. Such tabloid

papers not only conveyed the

prevailing atmosphere in the city

but also participated in its

creation. They were the main

builders of Benedict Anderson’s

“imagined community.” They created

the climate for new ideas and

popularized political concepts as

part of popular culture. Daily

tabloids displayed the diversity of

the connections between the South

Slavs that would create Yugoslavia.

My hope is that this article will

provide a stimulus for further

archival investigation of

“underground Yugoslavism” before the

First World War. Our subject is what John Lampe

called a change that was felt in the

atmosphere from the time when the

word “Yugoslav” entered the language

and came into everyday use (Lempi

2004: 63). This inquiry seeks to

capture that mood, to get a sense of

the milieu of ordinary people’s

thoughts and emotions. The main

sources are snapshots of events in

Belgrade, different cultural

activities that left their mark on

life in the capital and reflected

deeper political ideas and

processes. These occasions come from

theatre, concerts, sporting events,

and tourism. Together they fall

under the rubric of popular culture,

a relatively recent phenomenon which

democratized the political space by

giving voice to all members of

society. The analysis of these new,

modern spheres of urban life is

particularly important because it

shows that Yugoslavism existed not

only in the minds of certain

intellectuals and precious few

political leaders but that it

trickled down into the streets and

squares and spread from there. Here

in Belgrade was a population

newcomers, growing past 80,000 and

over two-thirds literate, a mixture

of students and state officials,

merchants and professionals, as well

as servants and day laborers. This

initial study of the phenomenon is

based on the new tabloid press of

the period. Our source is Večernje

novosti, chosen not only because of

its larger circulation than the

other tabloids but also because of

its political reputation as

conservative and anti-Yugoslav. Its

coverage nonetheless concentrated on

the atmosphere in the Belgrade

streets, reporting everyday events

without much comment. Such tabloid

papers not only conveyed the

prevailing atmosphere in the city

but also participated in its

creation. They were the main

builders of Benedict Anderson’s

“imagined community.” They created

the climate for new ideas and

popularized political concepts as

part of popular culture. Daily

tabloids displayed the diversity of

the connections between the South

Slavs that would create Yugoslavia.

My hope is that this article will

provide a stimulus for further

archival investigation of

“underground Yugoslavism” before the

First World War.

Spreading Yugoslavism

The daily press coverage of

Belgrade’s cultural life detailed

contacts between representatives of

the various South Slavs across all

cultural fields and celebrated the

mutual connections and interaction

that they established. The diversity

and richness of these connections

leave the impression that everyone

made an effort to create links and

facilitate the forming of even more.

Elite spheres of culture were

initially in the lead, but over time

Yugoslavism increasingly became part

of popular culture and involved a

growing number of institutions,

civil society organizations, and the

citizens themselves. This “descent

into the people” meant connecting

social groups and spreading ideas

even from Belgrade to the

hinterland.

The earliest contacts between the

various South Slavs began in the

theatre. As early as 1841, actors

from Zagreb arrived in Belgrade

under Prince Michael’s patronage to

help the first and newly established

theatre in the capital, the Đumuruk

Playhouse (Batušić 1969: 505). Later

in 1862, encouraged during Prince

Michael’s second reign by the “Law

on the Yugoslav Tripartite Kingdom

Theatre,” the Croatian Drama Theatre

came on a tour in 1862 via Pančevo

and Zemun to Belgrade. They

performed in the hall of the royal

brewery to an enthusiastic audience.

An atmosphere of “fraternal harmony

and love between the South Slavs”

was cited in numerous reports of the

Zagreb and Belgrade press (Batušić

1969: 506). Shortly after this first

visit, on 28 February 1863, the

Committee for a Permanent National

Theatre in Belgrade sent identical

letters to the management of the

Novi Sad and Zagreb theatres

offering future cooperation. This

cooperation was impeded by pressure

from Habsburg authorities to not

allow visits from Serbian theatres

on their territory. Despite the

growing political conflict between

Austria-Hungary and Serbia, these

contacts were never severed in

peacetime. Collaboration primarily

involved performing the plays of

Croatian authors in Belgrade

(Kukuljević, Frojdenrajh, Okrugić,

Ban, Bogović, and Vojnović) and of

Serbian authors in Zagreb (Sterija,

Subotić, Kostić, and Trifković)

(Batušić 1969: 507), presenting

translated foreign plays and, most

of all, exchanging actors, so that

from 1863 not one season went by

without actors traveling “across the

border” as guest performers. An

important moment for such

connections was the arrival of the

Croatian Andrija Fijan as actor and

first permanent director of

Belgrade’s National Theatre for the

1894–95 season.

The dynastic change in 1903 and King

Peter’s ascent to the throne brought

significant changes. This was a

great turning point in national

politics, and open discussion with

the other Habsburg South Slavs.

Their discourse about “liberation

and unification” began in Belgrade.

Although such recent interpretations

have seen this as an effort to

create a Greater Serbia, the

coronation of King Peter alone in

September 1904 and all the

festivities held in his honor

instead carried a Yugoslav tone. One

part of the coronation program was

the First Yugoslav Art Exhibition

organized by Pavle Vasić, which

gathered some 100 artists from all

the regions that would subsequently

form the united state. There was

also the First Yugoslav Youth

Congress, and the day before the

coronation a key event took

place—the Yugoslav Artistic Evening,

held at the National Theatre. The

program began with Marković’s

overture, and then Zajc’s “Evenings

on the Sava” and Ćorović’s “harem

depiction,” “He,” concluding with

Nedved’s “ecstatic song,” “Beloved

and young,” performed by the

renowned Slovenian Octet. Mara Ceren

performed Schubert on the piano and

Peter Stojanović played “two songs

accompanied by a pianoforte” on the

violin. The Croatian Mladost Choral

Society received a long round of

applause for its performance of

Novak’s songs “In the summer

twilight,” “To Matushka,” and “To

Dalmatia.”

Other events organized in 1904 as

part of the coronation festival

unambiguously advocated the

closeness of South Slav peoples,

using the adjective “Yugoslav” in

their title. In September 1904, the

Convention of South Slavic Youth was

held in Belgrade. December saw the

founding of “Lada,” an association

of Croatian, Slovenian, Serbian, and

Bulgarian artists. In Sićevo a

Yugoslav art colony was organized by

Nadežda Petrović, Ivan Meštrović,

and Rihard Jakopič; similarly, also

in fine arts, the Yugoslav art

gallery was founded in the National

Museum as the first collection of

twentieth-century paintings. In

1905, the following year, the First

Convention of Yugoslav Writers was

held, and the year after the

Convention of Yugoslav Teachers,

funded by the Serbian government and

opened by King Peter. A total of

four Yugoslav art exhibitions were

held, in 1904 in Belgrade, 1906 in

Sofia, 1908 in Zagreb, and 1912

again in Belgrade, where there was

also a performance of Koštana in the

National Theatre with an overture

entitled “The harmony of

Serbo-Croats.” From 1904 to 1906

there were four conventions of South

Slav journalists (Jovanović 2005:

134).

Music also opened a space for

creating further connections between

neighboring Yugoslav ethnic groups.

The first tour of the Belgrade

Choral Society marked the beginning

of musical connections. The press

took particular note and reported on

the Belgrade Choral Society’s guest

performance in Split in 1906. The

new tabloid paper Večernje novosti

covered this visit in detail,

writing about the excursions and

luncheons organized for the Belgrade

singers, the places they

photographed, and the boat rides

they took on the Adriatic. From

there the society continued on to

tour other places in Dalmatia.1

In that same year of 1906, our

featured tabloid also reported on

other sorts of musical

collaboration, which indicates that

networking extended down from the

elite level to popular culture.

Thus, in January 1906 the Students’

Mandolin Club of Croatian university

cities played in the Belgrade

University building, since this was

a kind of university cooperation.

Upon the arrival of Croatian

graduates from Osijek, newspapers

made a marketing effort to

popularize these cultural events,

encouraging prospective visitors to

come to the concert: “Belgraders

should visit in large numbers this

truly artistic concert of our

Croatian brothers.”2 The audience was

encouraged through the media to

assign a special meaning to these

events, as “for these concerts of

our young Croatian brothers and for

their stay with us special

preparations are being made, so we

can expect that their concerts will

be heavily attended and that our

young brothers will take away with

them the same fine memories from

Serbia as our Croatian brothers from

Sokoli took away.”3 After Belgrade

the mandolin orchestra and the

choral society from Osijek went on a

mini tour of Serbia, performing in

Niš, Kruševac, Vrnjci, and

Kragujevac. We see that ideas of

closeness were spreading into the

heartland beyond the capital’s

growing audience.

Cultural cooperation and networking

intensified after 1910, as may be

seen in the coverage of the

increasing number of guest

performances. In late fall of 1910,

there was a visit of the “Harmony”

society from Sarajevo, heralded for

days as “a great Bosnian” visit to

Belgrade. At the National Theatre

they held a gala concert where seven

pieces were performed, mostly works

by the Serbian composers Mokranjac,

Binički, and Marinković.4 There was a

visit of the choral society “The

Balkans” from Zagreb, which gave a

concert at the Hotel Casino

performing numbers by a variety of

composers. Apart from some European

selections, they sang pieces by

Mokranjac and Marinković, the

Slovenian composer Hudolin Satner,

and the Croatian composer Vilko

Novak with the piece “To Croatia.”5

New artistic creations also received

special attention. Boža Joksimović’s

new composition was to be called

“Yugoslavia,” intending to combine

Serbian, Bulgarian, Slovenian, and

Croatian songs.6 The composition was

supposed to blend in “Snohvatica” by

Zmaj, a Bulgarian brigand song, with

the Croatian Preradović’s “Jelica”

and the Slovenian Župančič’s “Iz

Bele Krajine.” As reported, the

lyrics were to be translated into

Serbian by Vladimir Stanimirović,

who “among us has done the most work

on Yugoslav poetry.”

The spread of Yugoslavism was also

influenced by the strengthening of

civil society, whose role in Serbian

public life of the late nineteenth

century was growing. As in other

European societies, the institutions

of civil society were engaged as

legitimate intermediaries. Civil

society spoke for new public

expectations, a medium that

transmitted newly formed social and

political demands to decision makers

(Habermas 1969: 12). Ultimately, it

was an expression of a need for the

ever-expanding democratization of

society. Over time, the

strengthening of society led to

growing social demands and the

emergence of a whole range of

institutions, primarily trade

associations, which presented the

demands of certain interest groups

to the government. By Jürgen Kocka’s

definition, such forerunners of an

awakened civil society included all

institutions that organized,

channeled, and assisted the voiced

of demands of newly awakened

citizens before the institutions of

the state. These were first line

institutions into which the

political, social, and cultural

energy of the growing civil society

was channeled. The spread of Yugoslavism was also

influenced by the strengthening of

civil society, whose role in Serbian

public life of the late nineteenth

century was growing. As in other

European societies, the institutions

of civil society were engaged as

legitimate intermediaries. Civil

society spoke for new public

expectations, a medium that

transmitted newly formed social and

political demands to decision makers

(Habermas 1969: 12). Ultimately, it

was an expression of a need for the

ever-expanding democratization of

society. Over time, the

strengthening of society led to

growing social demands and the

emergence of a whole range of

institutions, primarily trade

associations, which presented the

demands of certain interest groups

to the government. By Jürgen Kocka’s

definition, such forerunners of an

awakened civil society included all

institutions that organized,

channeled, and assisted the voiced

of demands of newly awakened

citizens before the institutions of

the state. These were first line

institutions into which the

political, social, and cultural

energy of the growing civil society

was channeled.

The public space for civil society

played an important role in

Yugoslavism’s networking,

contributing to “everyday

Yugoslavism,” informing and bringing

together cultural representatives of

the ethnic groups that after 1918

would form a joint Yugoslav state.

The conventions of guilds and other

professional gatherings held in

Belgrade in honor of King Peter’s

coronation in the fall of 1904

deserve further investigation, to

see where these links went over the

last prewar decade when high

politics made little progress.

The associations’ activities

included various formal events in

which they participated with their

colleagues from the neighboring

Habsburg provinces. So for instance,

the Stankovic Music Society staged a

gala in 1910 that included societies

from Slovenia, Croatia, and

Bosnia-Herzegovina: Slavec from

Ljubljana, Javor from Vukovar, the

Serbian Academic Singing Society

from Zagreb, Milutinovic from

Bosanska Krupa, Sloga from Sarajevo,

Sloga from Dubrovnik, and Branko

from Zadar.7

The Bosnia-Herzegovina Association

from Belgrade was also very active

in trying to link the two regions.

This association organized a series

of events, especially after

Bosnia-Herzegovina’s annexation by

Austria-Hungary in 1908, in which

solidarity was extended to “poor,

fraternal Bosnia.”8 From the limited

sources consulted here it is not

easy to determine the actual

“content” of these fraternal

sentiments, to what extent they were

Serbian or Yugoslav, or more broadly

pan-Slav. These identities existed

simultaneously, intertwining and

clashing. They acted inconsistently,

sometimes promoting Yugoslav unity,

sometimes a Russian connection, and

sometimes advocating separate

Serb-centered homogenization. The

ethnic groups that were to create

Yugoslavia surely developed distinct

forms of national consciousness in

the nineteenth century, but these

identities were soon followed by

sentiments for wider South Slav

integration or connections to the

pan-Slav movement. This mixture of

identities is particularly difficult

to unravel in the movements that

flourished after the

Austro-Hungarian annexation of

Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908 and the

stormy Serbian reaction to the

apparent end of any sort of Bosnian

political connection. The

overlapping and conflicting ideas of

Serbianism and Yugoslavism in the

decade leading up to the First World

War are important subjects for

Serbian historiography to explore.

In Western historiography, the

activities of Narodna odbrana are

taken as evidence only of plans for

Greater Serbia on the basis of its

semi-official creation in Belgrade

after the annexation, its volunteers

initially dispatched to organize

armed resistance in Bosnia, and its

later association with the militant

Ujedinjenje ili smrt based in the

Serbian army. But the role of its

Bosnian members from the 1909

agreement to confine themselves to

cultural activities has not been

sufficiently examined.

An incident in the Russian Club in

1910 provides some sense of the

conflicting mixture of interests in

Bosnia-Herzegovina. The program of

Bosnian-Herzegovinian Evenings did

have a Serbian overtone. Petar Kocić

read a poem; a minstrel performed

the song “Smrt Starca Vujadina”;

while Jefta Dedijer and Radoslav

Vasović delivered lectures on

neighboring Austro-Hungarian Bosnia.9

A few days after the event, Večernje

novosti objected to the program.

In organizing the “Days of

Bosnia-Herzegovina,” the

Serbian-Russian club completely

forgot our brothers of Mohammedan

faith, which in our understanding of

protecting the Serbian and Slavic

interests should not have happened.

Can it be that we want a Yugoslav

and Slavic union, while at the same

time we completely disregard those

closest to us? It is not our fault

that the Greeks forced their faith

upon us, nor is it their fault that

the Turks forced the Muslim faith

upon them. The chief thing is that

despite different forced faiths

neither we nor they have abandoned

our national feature, our common

native Serbian language. We are both

Serbs through and through … First we

need to work on bringing together

all Serbs, and only after we manage

this, we can prove that we know how

to bring together Yugoslavs and all

other Slavs.10

The statement demonstrates both the

attraction to assimilating Bosnian

Muslims, like Macedonians, as Serbs

but also the clear distinction

between Serbs and other South Slavs.

At least beyond Bosnia, this sort of

Yugoslavism was not simply a

disguise for a Greater Serbian

ideology. Although these programs

were not completely separate,

especially in the prewar decade,

press reports support the existence

of a distinction between these two

notions. Even in the conservative,

nationalist press, they were

perceived as two phases of

unification, with Yugoslavia as the

ultimate goal. Achieving the narrow

Serbian goals did not mean

abandoning Yugoslavism.

Civil society’s institutions,

primarily professional associations,

were an important part of the

networking process. Their

involvement brought Yugoslavism

“down to the people,” from the

cultural elite. A good illustration

of this dispersion was the visit of

Croatian innkeepers to their Serbian

colleagues. In March 1912, Zemun

hosted a convention of innkeepers,

an occasion which the Croatian

delegation used to cross into Serbia

and visit Belgrade. The Belgraders

picked up their colleagues in Zemun

by boat, and took them to Belgrade

where in Topčider they organized a

“comradely feast.” Tabloid coverage

diligently followed their itinerary.

After the reception in Topčider, a

dinner was organized in the Kasina

followed by an army band concert.

The next morning the guests visited

the Yugoslav exhibition, and in the

afternoon they went on an excursion

to Smederevo, while a marching band

saw them off.11

The 1910 concert of the Slovenian

Ljubljanski zvon choral society at

the National Theatre deserves

separate treatment because of its

several but less mixed messages. The

event was not just about artistic

exchange and cooperation, but also

had a humanitarian character,

because the concert came from the

desire of the Slovenian artists to

help the flood victims in Resava as

a charitable cause.12 This incident

speaks more to an impulse for mutual

aid then for artistic collaboration.

That a Slovenian choral society was

giving a benefit concert for flood

victims indicates that feelings of

empathy for Serbian society as a

whole were part of these newly

established Serbian-Slovenian

relations. This “national

solidarity” was a qualitative

advance over intellectuals’ original

utopian ideals and marked a

significant deepening of the

Yugoslav movement.

New forms of mass entertainment,

particularly tourism and sports,

helped in the networking of

individuals and groups who supported

and promoted the Yugoslav idea. Like

other forms of mass culture, they

too created a space for defining

national identity. Whether

discovering the natural attractions

and historic sites of the South Slav

lands, or strengthening physical

bodies for the creation of “new,

national men,” either were effective

mediums for constructing a positive

image of one’s nation. Itineraries

of school trips followed real or

imaginary national boundaries. The

emerging sports associations whose

stated objectives were virility,

heroism, and solidarity also served

as a training ground for national

homogenization, Yugoslav as well as

Serbian.

Tourism played a special part in

acquainting and connecting the South

Slavs with each other. Prominent

citizens of the capital brought

their new customs while vacationing

at the Adriatic beaches by the late

nineteenth century. Thanks to rail

links such trips were almost

exclusively to the Kvarner coast,

primarily Abacia (Opatija). Until

1908 the trip took two days, and it

was necessary to spend the night in

Fiume (Rijeka). Then newly shortened

by rail, newspaper ads touted a

quick journey now taking only one

day.13 Private letters or diaries

would reveal much more about the

first such vacations, but we also

have the press reporting on whether

this or that individual took a

shorter or longer vacation. Most

often, trips to the coast were

favored for medical reasons. For

example, Jaša Vekerić, a Radical

Party member, had gone for “some

recuperation.”14 Prominent politicians

also took long vacations, as when

the press informed readers that

Prime Minister Mihailo Vujić

vacationed in Abacia for a month.15 Tourism played a special part in

acquainting and connecting the South

Slavs with each other. Prominent

citizens of the capital brought

their new customs while vacationing

at the Adriatic beaches by the late

nineteenth century. Thanks to rail

links such trips were almost

exclusively to the Kvarner coast,

primarily Abacia (Opatija). Until

1908 the trip took two days, and it

was necessary to spend the night in

Fiume (Rijeka). Then newly shortened

by rail, newspaper ads touted a

quick journey now taking only one

day.13 Private letters or diaries

would reveal much more about the

first such vacations, but we also

have the press reporting on whether

this or that individual took a

shorter or longer vacation. Most

often, trips to the coast were

favored for medical reasons. For

example, Jaša Vekerić, a Radical

Party member, had gone for “some

recuperation.”14 Prominent politicians

also took long vacations, as when

the press informed readers that

Prime Minister Mihailo Vujić

vacationed in Abacia for a month.15

In advertising the seacoast and

encouraging a broader Belgrade

public to take such a long trip, it

was often pointed out that in Abacia

there were a growing number of

Serbian-owned stores, barbershops,

and rooms for rent. Visiting these

stores was encouraged, among other

things, by advertisements such as

“No Serb who visits Arhimandrija

(Abacia) should get a shave or a

haircut in establishments other than

those owned by a Serbian. One should

always help his kin.”16 Even these ads

indicate how much the two regions

were familiar with one another.

Visits to the coastal resorts

affected not only the guests from

Serbia, but also inevitably changed

the “host” surroundings, or more

precisely changed Abacia, where

stores selling Serbian goods were

opened, and barbers and renters

arrived, deepening the newly formed

mutual relations. Although this

advertisement ostensibly spoke of

ethnic divisions even when it came

to cutting hair, the appearance of

“Serbian barbers” for “Serbian

tourists” inevitably linked the two

regions and encouraged new

acquaintanceships.

Before the Balkan Wars another type

of tourism began developing on the

coast. Affluent Belgraders began

building villas by the sea, and such

endeavors were reported in the daily

press: “From Novi near Fiume comes

the news that a few days ago two

Serbs from Belgrade, D. Brankovic

and V. Lukic, bought land in one of

the most beautiful places right by

the sea to build villas for

themselves and their families.”17

Undoubtedly this new fashion had an

impact on both communities and the

influx of Serbian tourists and

“weekenders” helped establish closer

“neighborly” relations.

Special trips were organized for the

broader segments of society with the

primary purpose of introducing

“fraternal regions.” The first

officially organized pleasure trip

to Slovenia occurred in the summer

of 1905. According to the Belgrade

press, it originated from the need

of Belgraders to “return the favor

to Slovenians for their substantial

involvement in the coronation and

the opening of the First Yugoslav

Art Exhibition.” The program

included Serbian participation in

the ceremony held in honor of the

Slovene Romantic poet France

Prešeren as well as a visit to the

Postojna Cave.18 In advertising the

trip the organizers stated that they

expected no fewer than 130

participants, although we have no

data on how many people actually

went. The plan was to change trains

in Zagreb and for the tourists to

stay in the city for the whole

morning, including lunch.19

A large Slovenian tour to Belgrade

was organized five years later in

the summer of 1910. This was a visit

which was partly made in solidarity

with the flood victims in the Resava

region, but the whole occasion

caused great excitement in the

capital. The guests were hosted in

the fashionable hotel Građanska

Kasina in the city center, where the

most important balls, concerts,

exhibitions, and lectures of the

time were held (Stojanović 2008:

265). The program included a visit

to the grave of the recently

deceased Belgrade actress of

Slovenian origin, Vela Nigrinova, as

well as a visit to the Orthodox

Cathedral and other attractions. The

guests were taken on two excursions:

by boat to Smederevo and Topčider

where, as the press reported,

traditional festivities were taking

place. Afterwards a luncheon was

prepared in the famous resort of

Smutekovac as well as a kermis in

Kalemegdan.20 Their visit thus covered

considerable ground to include

Belgraders’ favorite places in and

out of the city.

The city press also paid

considerable attention to three high

school graduates from Slovenia who,

after the aforementioned Slovenian

visit, stayed in Belgrade. We learn

that the young Slovenians remained

in Serbia a whole month, using the

opportunity to explore different

corners of the country. Their desire

to get to know Serbia in detail can

be seen from their traveling across

the country on foot, going from

Belgrade to Obrenovac, Valjevo, and

on to Užice and Višegrad.21 Upon

returning to Ljubljana, they thanked

their Serbian brothers for the warm

welcome and a send-off that included

a newspaper’s effort to extend a

“hearty greeting” in Slovenian.22

In 1911, the year preceding the

Balkan Wars, the visits aimed at

deepening understanding between the

South Slav peoples intensified.

There was one particularly

interesting tour to Zagreb in

January 1912 by a group of 20-odd

prominent Belgraders, among them

Svetomir Nikolajević and Stanislav

Binički with their wives. Newspapers

reported that the well-known

Belgraders toured the city and

attended a performance of “Tosca” at

the Croatian National Theatre.

Interestingly, two prominent

Belgraders “came as envoys of the

Belgrade Freemason lodge” to attend

the opening ceremony of the Zagreb

lodge.23 Here we are not only reminded

of the importance of Masonic lodges

in Yugoslavia’s creation but also

see that their activities were

publically followed and reported.

Early tourist visits were not

limited to high society. As part of

the new popular culture, the

practice was publicized and reached

ordinary families. Thus, in the same

year as the Masonic visit, a school

trip took Serbian students to

Zagreb. They visited museums and

Maksimir, after which they proceeded

to Ljubljana and Trieste.24 In the

late summer Belgrade hosted a group

of Slovenes and Croats, “who came to

acquaint themselves with Serbs from

the Kingdom and with Bulgarians.”

The plan was to visit Jagodina, Niš,

and Belgrade.25

Agents of Yugoslavism

Although Yugoslavism became a major

subject once the state existed, as

noted above, its pre-1914

ideological roots have remained less

explored than the political

decisions which led to its creation

during the First World War. Although

it was long known as “the golden age

of Serbian democracy,” the domestic

dimensions of this last pre-1914

decade have been neglected by

Serbian historiography and have only

recently received critical attention

(Stojanovic 2003). Serbian

historiography has paid much less

attention to its domestic dimensions

than to foreign relations. This void

has opened the way for recent claims

that there was no momentum for the

Yugoslav idea before 1914. To the

contrary, any inquiry into public

addresses, parliamentary briefings,

and newspapers about Yugoslavism

would reveal that Yugoslavia was a

widely discussed concept among the

Belgrade political and intellectual

elite, widely disseminated by the

city’s lively press. Some

contemporaries went so far as to say

that the Yugoslav idea had

completely captured the sympathy of

the wider public. Left-wing

representatives of the Independent

Radical Party, writing in the

party’s daily paper in 1910, argued

that “the entire rational population

of Serbia, with the exception of the

patriots around Pravda, the

‘intellectuals’ around Večernje

novosti, and the politicians around

the departed Nedeljni pregled,

clearly sees the grand, historical

value of the Yugoslav idea. This

wondrous and lifesaving idea had in

the last seven or eight years made

tremendous progress. Today, without

any exaggeration, we can say: the

Yugoslav idea has captivated all the

better elements and wise people in

our country, and each day it reaches

new heights.”26 Neutral in party

politics but very much

Yugoslav-oriented, Politika

maintained as early as 1906 that

“the idea once represented only by

Štrosmajer became today the dominant

idea of every judicious Serbian and

Croatian politician.”27 Stojan Protić,

a major figure in the ruling

People’s Radical Party, who did not

then nor after the first

Yugoslavia’s creation share its

opposition to local autonomy,

authored a pamphlet about the

promising idea of balancing Serb and

Croat rights in a single state. With

the exception of conservative

Nedeljni pregled, he concluded,

“there are no known cases of people

in our nation who think differently”

(Protić 1911: 98).

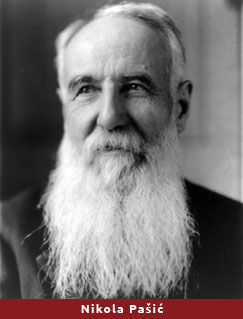

Nikola Pašić, prime minister for a

full eight years from 1903 to 1914,

avoided speaking openly of Yugoslav

unification, which would lead

directly to a conflict with the

neighboring Habsburg Monarchy. The

Serbian government had nonetheless

financed and actively supported all

Yugoslav events taking place in

Belgrade from 1904 forward

(Stanković 1985: 100). It was only

following the Serbian victory in the

First Balkan War that Pašić began

professing his allegiance to

Yugoslav unification openly. It was

then that the Radical Party

parliamentary club unequivocally

supported the proposal of the party

ideologue Laza Paču that the first

stage of liberation was completed

and that Serbia should be preparing

for the second stage, “national

unification of Serbs with their

Serbian, Croatian, as well as

Slovenian brothers” (Marković 1935:

9; Janković 1973: 75–76; Stanković

1985: 133). Pašić himself presented

this view to the Russian emperor

during his official visit in

February 1914 (Stanković 1984: 25).

Although Pašić ordinarily spoke

little about Yugoslav unification

(Stojanović 1997: 11), and his

writings and statements left hints

of a parallel minimal Serbian and

maximal Yugoslav program, reducing

his political goals only to Serbian

unification would be an ahistorical

simplification. Yugoslavism was

clearly present in his thinking ever

since his first letters from abroad28

or his 1890 book, the title of which

speaks for itself: “The harmony of

Serbo-Croats” [Sloga Srbo-Hrvata]

(Pašić 1995). Similarly, Pašić

already informed his closest aides

on 29 July 1914, the day after

Austria-Hungary declared war on

Serbia, that the main war aim was to

create a state whose borders would

follow the line

Klagenfurt-Marburg-Szeged (Draškić

1995: 213). The Ministry of Foreign

Affairs used this same projected

border in its late August 1914 memo

based on the premise that “all

Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes should

be united in a single unit”

(Stanković 1985: 147).29 Without prior

readiness for the unification to be

carried out in a Yugoslav framework,

such determination and dispatch

would not have been possible at the

very start of the war. It should

also be noted that Pašić’s closest

allies and also ministers in his

administrations were Milovan

Milovanović, Stojan Protić, and

Lazar Paču, all of whom openly

advocated Yugoslavism in the decade

before the war (Milovanović 1894,

1895; Stojanović 2003: 11). Nikola Pašić, prime minister for a

full eight years from 1903 to 1914,

avoided speaking openly of Yugoslav

unification, which would lead

directly to a conflict with the

neighboring Habsburg Monarchy. The

Serbian government had nonetheless

financed and actively supported all

Yugoslav events taking place in

Belgrade from 1904 forward

(Stanković 1985: 100). It was only

following the Serbian victory in the

First Balkan War that Pašić began

professing his allegiance to

Yugoslav unification openly. It was

then that the Radical Party

parliamentary club unequivocally

supported the proposal of the party

ideologue Laza Paču that the first

stage of liberation was completed

and that Serbia should be preparing

for the second stage, “national

unification of Serbs with their

Serbian, Croatian, as well as

Slovenian brothers” (Marković 1935:

9; Janković 1973: 75–76; Stanković

1985: 133). Pašić himself presented

this view to the Russian emperor

during his official visit in

February 1914 (Stanković 1984: 25).

Although Pašić ordinarily spoke

little about Yugoslav unification

(Stojanović 1997: 11), and his

writings and statements left hints

of a parallel minimal Serbian and

maximal Yugoslav program, reducing

his political goals only to Serbian

unification would be an ahistorical

simplification. Yugoslavism was

clearly present in his thinking ever

since his first letters from abroad28

or his 1890 book, the title of which

speaks for itself: “The harmony of

Serbo-Croats” [Sloga Srbo-Hrvata]

(Pašić 1995). Similarly, Pašić

already informed his closest aides

on 29 July 1914, the day after

Austria-Hungary declared war on

Serbia, that the main war aim was to

create a state whose borders would

follow the line

Klagenfurt-Marburg-Szeged (Draškić

1995: 213). The Ministry of Foreign

Affairs used this same projected

border in its late August 1914 memo

based on the premise that “all

Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes should

be united in a single unit”

(Stanković 1985: 147).29 Without prior

readiness for the unification to be

carried out in a Yugoslav framework,

such determination and dispatch

would not have been possible at the

very start of the war. It should

also be noted that Pašić’s closest

allies and also ministers in his

administrations were Milovan

Milovanović, Stojan Protić, and

Lazar Paču, all of whom openly

advocated Yugoslavism in the decade

before the war (Milovanović 1894,

1895; Stojanović 2003: 11).

Several other ministers widely

assumed to be opponents of

unification also made public

statements supporting such a state,

even if they had minor reservations.

Večernje novosti, identified with

anti-Yugoslav sentiments as noted

above, therefore serves nicely as

the major source for this article.

The tabloid provided enough coverage

of everyday events to suggest the

“spreading of Yugoslav air.” Stojan

Novaković, leader of the Progressive

Party, argued unambiguously in

Pravda: “let us unite, unite the

hearts of the man by the River Timok

and the one in Gruž on the Adriatic

Sea, the one from Skadar on the

Bojana and the one on the Morava,

the one on Una and the one on the

cold Vardar.”30 Even Pijemont, the

paper of the Black Hand militants,

which most closely identified with

promoting Greater Serbia, also sided

with the concept of a broader

unification: “Serbs and Croats

should not only officially be

considered one nation, but we should

also regard Bulgarians and

Slovenians their closest brothers,

while striving for unification or an

alliance between these fraternal

tribes should be the only Serbian

national policy.”31

These and many other articles,

statements, and speeches show that

across the political spectrum, from

Social Democrats who advocated a

Balkan federation, to independents

on the left, to at least some of the

ruling Radicals and the right-wing

Black Hand, the Yugoslav idea had in

the last prewar decade become

commonplace in Belgrade politics.

Tabloid papers are an appropriate

source for this study because, in

addition to basic information, they

also carried “gossip” to spice up

the bare details. In reporting local

news they often listed and commented

on the individuals who participated

in the events or belonged to the

organizational committees. We can

thereby track the social structure

of public life and see the role of

certain social groups and

occupations. Lists of organizers and

participants indicate that high

government officials supported the

meetings of “Yugoslavs.” By their

presence at these events, they

brought authority and at least

promised official support. The 1904

coronation ceremony was entirely

dedicated to Yugoslavism and spoke

unequivocally of the Karađorđević

dynasty’s support for the idea. At

other events too, even those

characterized as popular

entertainment, one could frequently

read in the papers that

representatives of the Crown were in

attendance, even when this was a

free concert for the people in

Kalemegdan.32 The city administration

for its part supported such

ceremonies, the municipal president

delivering a speech at the opening

of the Yugoslav ceremony when the

Zvon choir from Ljubljana33 came to

perform. As this tabloid reported,

the concert at the National Theatre,

apart from the representatives of

the Crown, was attended by the

diplomatic corps, giving it some

suggestion of international support.34

A sizeable number of “ordinary”

people moved through civil society

into the public arena, bringing

together different levels of

activity, where they placed their

private social position in the

service of a public one. They also

brought these public interests back

to their homes, social circles, and

families, thus linking the public

and private spheres and spreading

ideas through their everyday

discussion.

The organizers and lists of

participants serve as a guidebook

for tracking the national movements

and their advocates, combining

precisely the social groups

considered crucial for wider

popularization. A good example is

the first official visit of

Belgraders to Ljubljana, which as

noted above could have included as

many as 130 people. The organizers

came from the capital’s social and

intellectual elite. The president of

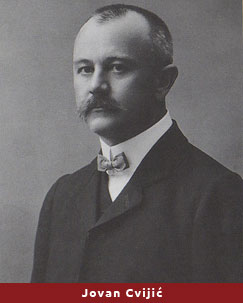

the committee was Jovan Cvijić, the

famous geographer and ethnographer,

one of the most ardent advocates of

Yugoslavism and the idea of a deeper

Dinaric connection among the South

Slavs beyond language or culture.

Also attending was Vladislav

Ribnikar, owner and editor-in-chief

of the leading independent daily

Politika. In addition to leading

scholars and journalists,

participants also included state

officials and a wealthy merchant,

Marko Vuletić. An advertisement

identified his store on the

fashionable Knez Mihailova street in

the city center as the place to

register for joining the trip. The organizers and lists of

participants serve as a guidebook

for tracking the national movements

and their advocates, combining

precisely the social groups

considered crucial for wider

popularization. A good example is

the first official visit of

Belgraders to Ljubljana, which as

noted above could have included as

many as 130 people. The organizers

came from the capital’s social and

intellectual elite. The president of

the committee was Jovan Cvijić, the

famous geographer and ethnographer,

one of the most ardent advocates of

Yugoslavism and the idea of a deeper

Dinaric connection among the South

Slavs beyond language or culture.

Also attending was Vladislav

Ribnikar, owner and editor-in-chief

of the leading independent daily

Politika. In addition to leading

scholars and journalists,

participants also included state

officials and a wealthy merchant,

Marko Vuletić. An advertisement

identified his store on the

fashionable Knez Mihailova street in

the city center as the place to

register for joining the trip.

Students who frequently organized

joint events also played a part in

disseminating this sense of common

South Slav identity. Bosnian visits

to Belgrade were prominent here.

Their day trips began each day at

the main university building,

indicating that its administration

also supported the independent

student movement.35 The organization’s

leadership was structured to feature

a Serbian female student as

president and a male student from

Mostar, Đihić, as vice president.

Newspapers emphasized that the

president, Ljubica Stakić, was

studying mathematics, reflecting

both intelligence and emancipation.

By this time, the University of

Belgrade took pride in its female

enrollment as a sign of

modernization.36

There were also trips for students

from the interior of Serbia, like

the one from the Kraljevo School of

Agriculture and Animal Husbandry.

They traveled with their teachers to

Zagreb, where they toured the city,

visited a museum, and farms. In

Križevci they were welcomed by the

local Agricultural School, and then

proceeded to Ljubljana.37 This rural

interaction was important not only

for connecting people from the

peasantry, the largest part of the

South Slav population, but for the

attention paid to it the Belgrade

press.

Emotions and Politics

The Belgrade tabloids often

“flavored” their coverage of events

with attention to the aroused

emotions of visitors and an ardent

audience reaction. The first major

visit of Croatian artists, at the

coronation of 1904, saw coverage

emphasizing the great excitement

that ensued. The promenade concert

at the National Theatre, with King

Peter and Crown Prince George

attending, prompted euphoric reports

that celebrated the excited

audience. “The emotions of every

listener were awakened and rattled,

and these feelings did not abate

until long after the audience left

the theatre. The theatre was full,

not a single empty seat, mostly

filled with Yugoslav-minded youth.

Excitement, fervor, freshness,

intelligence, and youth, and many

other things beautiful, ideal, and

richly enchanting—along with a

discussion about major, significant,

and lofty ideas—came to our National

Theatre last night to delight those

who enjoy Yugoslav art and

charismatic artists.” According to

the same article, the audience was

hugely impressed by the Oblic choral

society of Belgrade when they sang

“Slavia,” after which “the audience

experienced a real emotional storm

and responded with deafening

applause.”38

Various guest appearances by

Croatian artists prompted more press

comment on the mood in the capital’s

streets. Note the reaction after the

visit of “our beloved guest and

artist, Ms. Krnjić,” a Croatian

actress.39 As recorded in Večernje

novosti, a farewell event was

organized in the National Theatre

Square to see her off to Zagreb:

“When Ms. Krnjić appeared at the

door after the show, excited young

people who waited to see her broke

into enthusiastic cheers: ‘Long live

Ms. Krnjić.’ … The cart was drawn by

enthusiastic young people, and all

around it from hundreds of throats

came the cry: ‘Long live Sadoma!

Long live Ms. Krnjić.’” Similar

reactions followed the visit of Nina

Vavra, a Zagreb actress who came to

the National Theatre in April 1908,

causing an outpouring of warmth from

a newspaper reporter: “Again she

delivered her lines clearly and

beautifully in her southern accent,

and she was simply a delight to

listen to.”40 As a darling of

Belgrade’s critics and audiences,

Nina Vavra signed an exclusive

contract with the Belgrade Theatre

the following year.41

A highlight of this cooperation was

the visit of the Zagreb Opera to

Belgrade in the spring of 1911. Its

performances were so much

appreciated that they gave 16

performances instead of the planned

six. They presented the works of

Smetana, Tchaikovsky, Bizet, Verdi,

Puccini, and Albinoni (Batušić 1969:

507), prompting the manager of the

National Theatre, Milan Grol, and

the Zagreb manager to begin

negotiations concerning regular

guest appearances and lasting

cooperation.42 These performances were

cut short by the Balkan Wars that

began the following year. Večernje

novosti, otherwise regarded as close

to the deposed Obrenović dynasty and

the Progressives, and accused by

some of having an anti-Yugoslav

attitude, carried day-to-day reports

on the visit of more than 120

artists. Writing about operatic

guests’ appearance, the newspaper

said that “the visit of our

fraternal Croatian opera captivated

Belgraders,” whom they advised not

to doubt “that everything stated in

these dense lines comes from sincere

hearts, as sincere as last night’s

deafening cheers.”43 The performance

played before a full house, while

reviewers concluded that “the visit

of the Croatian opera can be

considered a joyous occasion for

Belgrade.”44 This was just part of the

general atmosphere which emphasized

fellowship with other South Slavs as

supported by some Serbian officials,

if not the Prime Minister and his

circle. But for him, Serbian

officials and the entire opposition,

Serbia was to serve as an

Italian-style Piedmont for unifying

all South Slavs and not just Serbs.

Tabloids such as this one also

reported on the practice of

welcoming guests and seeing them off

at the train station. The hosts

often welcomed guests at the nearest

Austro-Hungarian town of Zemun, from

where they brought them by boat,

often accompanied by a musical band,

to Belgrade.

One particularly emotional occasion

was the arrival of visitors from

Tuzla, led by Smail-aga Ćemalović, a

Bosnian Muslim graduate student from

Herceg Bosna.45 The guests were first

welcomed in Zemun and then

ceremoniously brought to Belgrade.

At Zemun, the waving of

handkerchiefs and hats began from a

great distance, while at the

Belgrade train station the welcome

was both massive and festive.46 The

coverage repeatedly emphasized the

large attendance at the events held

in the Tuzlans’ honor, adding that

“by witnessing the numbers attending

their performances, our esteemed and

dear guests could tell how we

respect and cherish them.”47 The

organizers were also thanked when

they “wholeheartedly welcomed and

escorted our Sarajevan sisters and

brothers,”48 and then gave them a

send-off from Belgrade that was

“magnificent and enthusiastic.”49 It

was reported that individual

citizens in Belgrade in their

enthusiasm wanted to give a personal

contribution to newly established

relations and emotions. Many of the

Belgraders “who met the members of

Sloga last winter sent their

greetings to Sarajevo by a new means

of communication, the telegraph.”

Most importantly, it was the

Belgrade press that not only

described the Yugoslav atmosphere of

numerous festivities, send-offs, and

welcoming receptions, but also

actively participated in the

creation of this new sense of

community by anticipating an

imaginary union within a future

South Slav state. There was no

mention of Greater Serbia.

Conclusion

These initial results suggest that

the Yugoslav idea was much more a

part of the lives of the urban elite

and ordinary residents in Belgrade

before the First World War than

previously thought. As noted

initially, further research is

needed, but even this snapshot of

tabloids and some other press

coverage suggests that a “Yugoslav

sentiment” had spread to many

segments of society, from audiences

attending cultural events to

innkeepers’ associations to

agricultural school students. This

data calls into question the

hypothesis that Yugoslavism never

went through all the stages of

Hroch’s well-known periodization of

national movements (1985). It began,

as predicted in Stage A, with

“awakened” intellectuals. In the

case of Serbia, however, practical

political support for Yugoslavism,

especially from the ruling party and

its leadership, as predicted in

Stage B cannot be demonstrated. But

the wider popular support

anticipated in Stage C, which spread

from the urban elite and the press

to the Belgrade public, does

nonetheless seem to have taken hold.

The evidence presented here calls

into question the claims that

pre-1914 Yugoslavism never “reached

the people” (Djordjević 1974: 14).

This article suggests instead that

the idea was more deeply and widely

accepted than previous, largely

political scholarship has

acknowledged. Here cultural history

and the social history of everyday

life have more contributions to

make.

If we accept and expand on these

conclusions them with additional

research, we could perhaps better

understand the recent Yugo-nostalgia

in many parts of the former

Yugoslavia, again mostly in popular

culture. We may in the process find

support for the hypothesis that

Yugoslavism was stronger than either

of the two Yugoslav states,

outliving them both. This theory

would challenge post-1989 notions of

Yugoslavia as an artificial creation

from the start rather than two

states created after two World Wars

and burdened with their

consequences.

Bibliography

Batušić, S . 1969. “Gostovanja

Narodnog pozorišta u Zagrebu”

[trans]. In Jedan vek Narodnog

pozorišta, pp–pp. Belgrade: Narodno

pozorište.

Djokić, D, ed. 2003. Yugoslavism:

Histories of a Failed Idea,

1918–1992. London: Hurst and Co.

Đorđević, D. 1974. “Yugoslavism:

Some Aspects and Comments.”

Southeastern Europe 1, no. 1:

192–201 .

Gaćeša, N, LJ Mladenović-Maksimović,

and D Maksimović. 1993. Istorija za

8. Razred [trans]. Belgrade: Zavod

za izdavanje udžbenika.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1969. Javno

mnjenje: Istraživanje u oblasti

jedne kategorije građanskog društva.

Belgrade: Kultura . German original:

1962. Strukturwandel der

Öffentlichkeit: Untersuchungen zu

einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen

Gesellschaft. Neuwied: Luchterhand.

Hroch, Miroslav. 1985. Social

Preconditions of National Revival in

Europe. New York: Columbia

University Press.

Jovanović, M et al. 2005. Moderna

srpska država: Hronlogija 1804-2004

[trans]. Belgrade: Historijski arhiv

Beograda.

Janković, D. 1973. Srbija i

jugoslovensko pitanje 1914-1915

[trans]. Belgrade: Institut za

savremenu istoriju.

Lempi, Džon R. 2004. Jugoslavija kao

istorija: Bila dvaput jedna zemlja.

Belgrade: Dan Graf. English

original: Lampe, John R. 1996.

Yugoslavia as History: Twice There

Was a Country. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Marković, L. 1935. Jugoslovenska

država i Hrvatsko pitanje 1914-1932

[trans]. Belgrade: Prosveta.

Milovanović, M. 1894. Naša spoljna

politika [trans]. Belgrade:

Čitaonica.

———. 1895. Srbi I Hrvati [trans].

Belgrade: Čitaonica.

Protić, S. 1911. Hrvatske prilike i

narodno jedinstvo Srba i Hrvata

[trans]. Belgrade.

Pašić, N. 1995. Sloga Srbo-Hrvata

[The harmony of Serbo-Croats].

Belgrade: Stubovi kulutre.

Rusinow, D. 1990–91. “To Be or not

to Be? Yugoslavia as Hamlet.” Field

Staff Reports, no. 18: 1–13.

Stanković, Đ. 1984. Nikola Pašić,

saveznici i stvaranje Jugoslavije

[trans]. Belgrade: Nolit.

———. 1985. Nikola Pašić i

jugoslovensko pitanje [trans].

Belgrade: BIGZ.

Stojanović, D. 1997. Nikola Pašić u

Narodnoj skupštini, 1903-1914

[trans], bk. 3. Belgrade: Službeni

list.

———. 2003. Srbija i demokratija

1903-1914: istorijska studija o

“zlatnom dobu” srpske demokratije

[trans]. Belgrade: Udruženje za

društvenu istoriju.

———. 2008. Kaldrma i asfalt,

urbanizacija i evropeizacija

Beograda 1890-1914 [trans].

Belgrade: Udruženje za društvenu

istoriju.

|