|

Case

study 2

As in most of

Europe during the past century, the

everyday life of the majority of the

population in both Yugoslavias was

taking big strides toward change.

Shorter and traumatic periods of

high mortality rates and destruction

(during the wars) alternated with

long peaceful periods, and the

initial and final results of both

Yugoslav half-times pointed to an

increase in the quality of life.

This was especially felt among those

strata of the population – workers

and most peasants – whose initial

position was low and unenviable and

their basic material safety

uncertain over both the short and

long term. After two wars, social,

economic and cultural circumstances

were guided by the idea of shaping a

better environment and significant

leaps towards moderization, which

was especially pronounced during the

second post-war period, when the

society was shaped according to the

principles of socialist

modernization, based on rapid

industrialization, electrification

and urbanization. New everyday

practices and customs were permeated

with new conceptions, shaping

different identities and gradually

changing long-established

mentalities.

Due to the

initial, predominantly agrarian,

structure of the population, the

village-city relationship is the

paradigm within which it is possible

to consider the complexity of social

change since the place of residence

implied a slower or faster movement

towards modernization. The quality

of this movement was also determined

by distinct regional differences

within the country. Moving from one

environment to another meant

breaking up the centuries-long

structure of social relations –

usually patriarchal and sometimes

even feudal – and entering the world

of a more distinct individuality

that was integrated, on a different

basis, into the collective, ranging

from the nuclear family to the

broader community. Strict parental

authority within the extended family

or cooperative community was fading

away, while new supportive social

networks, like those of neighbors,

friends and colleagues, as well as

extended family and homeland

networks, were taking shape. Within

these communities women and

children, the group to which the

20th century brought emancipation,

were becoming increasingly

independent, so that their role in

the everyday life of their community

was increasingly pronounced, their

successes increasingly important and

their defeats increasingly hard to

accept. The new role of woman who

was now entering the world of the

labour force and public life, took

shape simultaneously with the new

role of man, who was more clealry

turning to his family and becoming

emotionally engaged in it. Social

upheavals could mean the loss of old

traditions and the adoption of new

ones, transition from old rituals to

new collective public events, the

weakening of religious feelings and

the acceptance of secularism, or a

different understanding of

religiousness. At the same time,

literacy and the educational level

of the population were on the rise,

thus creating conditions for a

greater openness of society and the

mitigation of class differences. In

the 1980s, the grandchildren of

illiterate grandparents could play

computer games. After growing up in

fields or pastures, they could spend

their youth working on an assembly

line or at an office desk. The

transition from peasant clothes to

civilian clothes and blue jeans,

from the woman's more or less

covered head to coloured hair and

perms, from sleeping on straw to

sleeping on a comfortable mattress,

was very fast. The participants in

all these changes included adults

and their children who were, for

example, mostly called Vesna,

Snežana, Ljiljana, Zoran, Dragan and

Goran in Belgrade in the 1960s, and

Snježana, Gordana, Branka, Željko,

Tomislav and Mladen in Zagreb at the

very beginning of the 1970s. In many

respects, their everyday life, like

that of their parents and

grandparents, has so far been

studied historiographically,

including related disciplines, but

it is still necessary to deal with

those processes and practices for

which there exist only rare data and

general notions handed down orally

or in print.

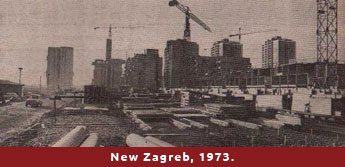

Apartments, Household Appliances, a

Better Diet...

During the past

century, the housing situation

improved for the majority of the

population. In the inter-war period,

the housing infrastructure outside

cities was either poor or

non-existent, lacking electricity,

water and sewage connections. Living

conditions in municipal workers' or

peripheral settlements were poor.

Life in the villages located in the

northern part of the country was

better, but in other regions those

who had a bed of their own were

rare. In the underdeveloped parts of

the country, the bed was usually

reserved for the head of the

household, grandfather, sick person

or small children, while numerous

other housedhold members slept on

the floor, together with the animals

in winter and outdoors in summer. A

great wave of urbanization took

place in the second half of the

century when settlements with larger

residential buildings and

skyscrapers were built. New cities

or larger urban complexes, such as

New Belgrade, New Zagreb, New

Gorica, Velenje and Split 3, were

also built. From the aspect of urban

planning, the reconstruction of

Skopje after the disastrous

earthquake of 1963 was especially

successful. These new settlements

were based on contemporary urban

planning and architectural concepts

such as residential buildings with

social amenities, surrounded by

green areas and having no direct

access to major roads. Kindergartens

and schools, parks, health centers,

trading and small-scale craft

facilities were also built according

to plan. The provision of additional

amenities was often delayed, so that

such parts of the city were often

called dormitories: “People go home

to the settlement only to eat and

sleep, while for everything else

they must go into town”. However,

due to a higher percentage of young

families and a greater number of

children, their life was far from

the usual notion of alienated urban

life. Each year, from the early

1960s through the 1980s, 100-150

thousand apartments were built and

one third of them was built by the

socially-owned sector. These

apartments were given to workers on

the basis of their occupancy right

acquired in the enterprises and

institutions where they were

employed. A survey shows that in the

years of peak housing construction,

that is, during the late 1970s and

early 1980s, all three-member worker

households had electricity, almost

of them had water and sewage

connections, one third had central

heating and eight out of ten had a

bathroom and toilet in the

apartment. These above-average

results were contributed to by

certain rural areas and,

occasionally, illegally built

peripheral urban settlements.

Namely, the state tacitly allowed

the illegal construction of entire

individual housing complexes in

order to mitigate the housing

problem among the fast-growing urban

population. The state did not

succeed in meeting the demand for

telephone line connections fast

enough. It often took years to get

one, so the arrival of the telephone

was a reason for celebration and

calling up all and sundry to spread

the happy news. During the past

century, the housing situation

improved for the majority of the

population. In the inter-war period,

the housing infrastructure outside

cities was either poor or

non-existent, lacking electricity,

water and sewage connections. Living

conditions in municipal workers' or

peripheral settlements were poor.

Life in the villages located in the

northern part of the country was

better, but in other regions those

who had a bed of their own were

rare. In the underdeveloped parts of

the country, the bed was usually

reserved for the head of the

household, grandfather, sick person

or small children, while numerous

other housedhold members slept on

the floor, together with the animals

in winter and outdoors in summer. A

great wave of urbanization took

place in the second half of the

century when settlements with larger

residential buildings and

skyscrapers were built. New cities

or larger urban complexes, such as

New Belgrade, New Zagreb, New

Gorica, Velenje and Split 3, were

also built. From the aspect of urban

planning, the reconstruction of

Skopje after the disastrous

earthquake of 1963 was especially

successful. These new settlements

were based on contemporary urban

planning and architectural concepts

such as residential buildings with

social amenities, surrounded by

green areas and having no direct

access to major roads. Kindergartens

and schools, parks, health centers,

trading and small-scale craft

facilities were also built according

to plan. The provision of additional

amenities was often delayed, so that

such parts of the city were often

called dormitories: “People go home

to the settlement only to eat and

sleep, while for everything else

they must go into town”. However,

due to a higher percentage of young

families and a greater number of

children, their life was far from

the usual notion of alienated urban

life. Each year, from the early

1960s through the 1980s, 100-150

thousand apartments were built and

one third of them was built by the

socially-owned sector. These

apartments were given to workers on

the basis of their occupancy right

acquired in the enterprises and

institutions where they were

employed. A survey shows that in the

years of peak housing construction,

that is, during the late 1970s and

early 1980s, all three-member worker

households had electricity, almost

of them had water and sewage

connections, one third had central

heating and eight out of ten had a

bathroom and toilet in the

apartment. These above-average

results were contributed to by

certain rural areas and,

occasionally, illegally built

peripheral urban settlements.

Namely, the state tacitly allowed

the illegal construction of entire

individual housing complexes in

order to mitigate the housing

problem among the fast-growing urban

population. The state did not

succeed in meeting the demand for

telephone line connections fast

enough. It often took years to get

one, so the arrival of the telephone

was a reason for celebration and

calling up all and sundry to spread

the happy news.

Until the mid-20th

century, shifts in equipping

apartments and houses with furniture

and household appliances were

modest. In 1938, the price of a

kitchen table was equal to 70

percent of a salary on the first and

second pay scale, which was received

by every tenth worker. An enamelled

stove cost as much as the monthly

salary on almost the highest,

eleventh pay scale, which was

received by every twentieth worker.

Laundry was washed by hand and

washing was often part of the social

life of women who would take this

opportunity to get together. Over

time, cleanliness standards

improved. Home and personal hygiene

became increasingly important,

especially in the 1960s when there

appeared an automatic washing

machine that cost as much as three

times the average salary. Sales

increased rapidly and by 1973 every

third Yugoslav household had an

automatic washing machine and by

1988 – two out of three households.

This machine greatly facilitated

housework, so that housewives could

also do something else – pay more

attention to their children or enjoy

leisure time. It was increasingly

supplemented by TV sets, record

players and tape recorders. By 1973,

every second household owned a TV

set. In 1978, its price was equal to

the average salary, and byl 1988 a

black-and-white or colour TV set was

owned by 96 percent of

non-agricultural households and 58

percent of agricultural households,

which otherwise lagged behind in the

purchase of household appliances.

The TV set brought the greatest

number of changes into family life;

it assumed a central place in the

living-room and became the most

accessible source of entertainment

in leisure time. The light of the TV

screen brought together household

members as the fireplace had done

before.. Other appliances also found

their way to users, but at a

different pace. Up to the end of the

1980s, a vacuum cleaner was used by

two out of three households and a

refrigerator by nine out of ten; an

electric or gas stove was owned by

all households and only a very few

still used wood-burning stoves.

During the same decade, meat

shortages and purchases of larger

amounts of meat through trade unions

or from private sources enhanced the

importance of freezer chests and

drawers: “I cook a larger amount and

then divide it into daily portions.

I put everything in the freezer and

everyone will reheat their portion

later on. If it weren't for this

aid,I don't know how we would eat.

The freezer chest is of the greatest

help to me. I would sacrifice both

washing machine and vacuum cleaner,

but I couldn't give this up.”.

Food supply

problems, shortages and hunger were

not only the result of wartime and

post-war circumstances; they also

depended on weather conditions and

the situation in the countryside,

which was the only or main source of

supply. However, the problems also

included overpopulation,

fragmentation of land holdings,

technological backwardness and the

burden of debt. In the 1920s and

1930s as high a percentage as 75-80

of the population earned their

living exclusively from agriculture.

The years 1935, 1950 and 1952 were

especially dry. During the first

drought, hundreds of children from

Lika, the Croatian coast, Dalmatia

and Herzegovina were sent to regions

north of the Sava. The wave of

droughts in the early 1950s

coincided with the already

aggravated food supply and decline

in agricultural production. Post-war

hunger would have been even more

pronounced if it had not been for

shipments from the United Nations

Relief and Rehabilitation

Administration (UNRRA). From 1945 to

1952, the government resorted to

rationed or guaranteed supply,

dividing the consumers into

categories and restricting the

availability of goods, so that they

could only be obtained by presenting

a ration book. Thereafter, food

supply was normalized, but the

average food consumption and the

energy values of foods were not

satisfactory until the 1960s.

According to the statistical data,

consumption reached its maximum in

1982. Thus, per capita consumption

included, for example, 149 kg of

wheat products, 61 kg of potatoes,

96 kg of other vegetables, 52 kg of

meat and meat products, 3.8 kg of

fish, 101 l of milk and 187 eggs.

Accordingly, daily consumption

included about 16 dag of fruits and

15 dag of meat, as well as an egg

every second day. The food industry

gained great momentum in the second

half of the century, while a

modernized diet also included packet

soups and cooking in the pressure

cooker. Numerous cookery books were

published; there appeared TV shows

giving cooking instructions, and

recipes for the preparation of

various dishes and cakes were

exchanged. Travel and migration

within the country contributed to

the establishment of culinary

linkages, the permeation of

different tastes, the mixing of

traditional cuisines and the

formation of new food habits.

Despite the existence of numerous

restaurants and cafes, workers'

canteens, school cafeterias, the

first pizzerias and fast food

restaurants, the main cooked meal

was most often eaten at home with

the family where the womenfolk were

still in charge of food provision

and cooking.

A Rise in Consumption

Nutrition and

hygiene greatly influenced the

health of the population. In some

parts of the country the rural

population did not go to the doctor,

at least not until the mid-century.

They preferred to turn for help to

quacks, herbalists and medicine men.

Health culture and the availability

of doctors in the first Yugoslavia

were not sufficiently developed, so

significant steps were taken towards

changing people's understanding and

modernizing the system, with the

emphasis on prevention and hygiene

activities, as well as the

development of social medicine. In

the late 1930s, 7.5 percent of the

population was covered by social and

health insurance, but the state

succeeded in developing a system of

two hundred or so hospitals and over

five hundred social-medicine

institutions, including institutes

of hygiene and public health

centres. However, the masses still

remained without regular health care

and were exposed to epidemics of

tuberculosis, malaria, trachoma and

other diseases.

The post-war

development of medicine and health

institutions made possible a greater

availability of doctors and an

almost fivefold increase in the

number of hospital beds (in 1986

there were about 143,000), while all

services were covered by mandatory

health insurance. Regular medical

check-ups and mandatory vaccination

of the population were also

organised. Occupational medicine and

an occupational safety system

provided greater security for the

employed. Pensions and homes for the

elderly instilled confidence in

end-of-life care. Thanks to better

health and hygiene as well as

improved socio-economic conditions,

the estimated life expectancy for

those born in the early 1980s was 68

years for men and 73 for women, that

is, twenty or so years longer than

that for the generations born in the

1940s. For the same reasons, infant

mortality declined from 143 per

thousand in the 1930s to 27 per

thousand in the mid-1980s, ranging

from 12.6 per thousand in Slovenia

to 54.3 per thousand in Kosovo. In

the mid-20th century, Yugoslavia

underwent a demographic transition:

the birth and death rates declined

to 15 and 9 per thousand

respectively. In the early 1950s,

the higher level of development

brought about family planning and

expansion of the right to abortion.

During the 1960s, Yugoslavia also

experienced a sexual revolution,

while a more liberal attitude toward

homosexuality led to its

legalization in some parts of the

federation.

Trade

modernization and the spread of

consumer culture were largely

changing the consumer's purchasing

behaviour and attitude towards

goods. Traditional trade at fairs

and markets – implying direct

buyer-seller relationships,

negotiating prices, occasional

exchanges of goods and an inevitable

backdrop of noises, smells and

colours – were preserved in rural

and urban environments, but were not

the only methods of purchasing

goods. Green markets were the

meeting place of the urban and

rural, or industrial and

agricultural worlds, which

supplemented each other well since

urban citizens needed goods from the

immediate vicinity on a daily basis.

In big cities there were department

stores, which had been known as

temples of consumer culture since

the 19th century. They represented

both selling and exhibition spaces

and usually attracted

middle-to-upper class customers.

However, there were even more

smaller and technically ill-equipped

shops. In the 1920s, there were more

than 100,000 shops of this type,

while in the 1930s their number

remained at about 86,000, which

meant that there was one shop per

182 inhabitants or, more precisely,

one food shop per 277 inhabitants.

These ratios were two times better

in comparison with only 40,000 shops

in the post-war period. Due to

reorganization and nationalization,

their number decreased to 35,000 in

1955, but thereafter began to

increase, reaching 100,000 in the

late 1980s. Being used to

communication with the seller who

would show them goods, put them on

the counter and collect payment,

buyers were faced with an unknown

and quite new method of sales when

self-service shops appeared. The

first such shop was opened in 1956,

in the town of Ivanec in northern

Croatia. Thus, strolling around the

aisles, picking up

industrially-packaged goods within

close proximity and spending more

time on shopping were becoming part

of everyday life. In Yugoslavia,

less than ten years after the

opening of the first self-service

shop, there were almost a thousand

shops of this type, while in the

second part of the 1980s there were

seven times more. During the same

period, the number of department

stores increased at the same rate

and exceeded the figure of 700.

Modernization of the trade network

and methods of sale formed part of

the development of consumer culture,

whose key features, especially among

the upper and middle strata of the

population, were already present in

the inter-war period. However,

consumer culture was only embraced

by all strata during the period of

higher economic growth and living

standards, so that in the late 1950s

and during the 1960s one could speak

about the formation of a Yugoslav

consumer society. At the popular

music festival in Opatija in 1958,

the winning song Little Girl, better

known for its refrain Papa, buy me a

car... buy me everything!, marked

the beginning of the consumer

revolution.

Daily shortages

did not lastingly characterise

Yugoslav trade. However, between

1979 and 1985, due to an economic

crisis, there were shortages of oil,

detergents, coffee, chocolate, corn

cooking oil, citrus fruits, hygiene

items and the like. For the first

time since the immediate post-war

period, citizens waited in line and

coped with the situation in various

ways. Whatever could not be found in

the country between the 1960s and

1980s came through private channels

from abroad: people would travel

usually to Italy and Austria, and

make purchases within a day. Goods

were also brought in by Yugoslavs

working abroad and tourists. Customs

officials at border crossings

sometimes met women wearing fur

coats in the summer heat, or men

wearing several pairs of trousers.

The earnings of about one million

Yugoslav workers temporarily

employed abroad flowed into domestic

banks. In addition,, these workers

were also bringing new life habits.

However, an even stronger engine of

consumerism was tourism.

Transport Development and Population

Mobility

Population

mobility in this territory was poor.

Life mostly unfolded in the vicinity

of one's place of birth. The culture

of travel began to develop only in

the second half of the century. Up

to then, the rural population would

most often go only to a fair or for

pilgrimage, usually on foot, or

emigrate to European and overseas

countries, or move within Yugoslavia

as part of land reform and

colonization. During the 1920s and

1930s, the number of rail passengers

doubled and reached over 58 million.

The maximum number was reached in

1965 – 236 million. Before the

Second World War, there were more

than 900 buses providing public

transport services on almost 500

intercity lines. In the early 1950s,

there were about 15 million bus

passengers, while 30 years later

there were even 70 times more – over

one billion. The bus was absolutely

the most popular form of public

transport. For example, according to

relevant data for the late 1970s and

early 1980s, maritime transport

services were used by up to about 8

million passengers each year, while

air transport reached its peak in

the second half of the 1980s,

exceeding 6 million passengers. At

that time, the Yugoslav fleet

operated about 250 routes with 50

planes. Most of the credit for these

figures should be given to Yugoslav

Airlines (JAT) which, as the key air

carrier, connected 53 cities on five

continents. Domestic passengers were

attracted by such slogans as “The

shortest route to the sun”, or

“Turning a trip into a vacation”.

The beginnings of the first

scheduled passenger airline service,

Aeroput, were much more modest.

During the ten years of its

existence, until the late 1930s, it

increased its fleet to 14 planes and

carried a modest number of more

affluent passengers – about 13,000.

Down on the

ground, roads still bore the burden

of the greaterst number of

passengers, but during the inter-war

period there were still no larger

infrastructure investments.

According to statistics, unpaved

roads were prevalent until the early

1980s, although the first highway

sections were constructed in the

early 1970s. The country's

development level and way of life

were unable to make possible

anything more than a rather slow

development of automobile culture.

In 1938, only 13,600 cars and 7,700

motorcycles were registered, which

means that horse carriages and

occasionally bicycles were still the

dominant modes of personal

transport. After the Second World

War, up to the 1960s, people most

often drove motorcycles. In 1955,

however, there appeared the Zastava

750, popularly called “Fićo”, “Fića”

or “Fičko”, the first Yugoslav

passenger car and the first product

of cooperation between the Zastava

factory in Kragujevac and the

Italian Fiat, which were to roll

down down the assembly line for 30

years. The importance of this first

car in the country's motorisation

was not even overshadowed by

Zastava's later basic models:

Zastava 101 or “Stojadin” produced

in 1970, or Jugo 45 produced in

1980. While the price of more

expensive Western car models was

equivalent to 40 or more average

monthly salaries, a Fića and

Stojadin cost 13 and 20 monthly

salaries respectively in 1971.

However, money was found and the

country embarked on a fast

motorization process in which the

car was becoming a status symbol. In

1970, one newspaper printed a

photograph of a man from Sandžak

with his car in front of a

dilapidated shack after deciding to

invest money first in a Fića and

then in his home. It was also

written about the residents of a

Macedonian village on Mount Šar who

kept their forty or so cars in the

neighbouring town of Tetovo because

their village had no connection to a

road. In 1972, butcher Štef Galović

told journalists that owning a car

was not a luxury; it was his right

after so many years of service. Many

people were guided by precisely this

principle. In 1961, there were as

many as 238 Yugoslavs per passenger

car, 10 years later – 24 and in the

late 1980s – seven on average; in

Kosovo there were as many as 23

persons per passenger car and only

four in Slovenia. After being

considered a luxury, owning a car

was gradually becoming the sign of a

common standard of living. However,

it was still viewed as a striking

consumption item and the most

expensive asset kept outside one's

safe home. It enjoyed the status of

a pet or family member, so that it

could often be found on family

photographs. A car was treated with

personal or family pride. Its owner

purchased accessories for it, its

engine was maintained and its body

was polished. In return, it

faithfully served its owners,

helping them to carry out everyday

tasks, whose pace and success were

becoming increasingly dependent just

on it, as well as to conquer new

spaces during excursions and

travels. Thus, it was becoming the

symbol of freedom because one could

travel by car almost everywhere at

any time, regardless of public

transport lines and timetables.

Simply enjoying the ride became part

of everyday life. In 1938, only 13,600 cars and 7,700

motorcycles were registered, which

means that horse carriages and

occasionally bicycles were still the

dominant modes of personal

transport. After the Second World

War, up to the 1960s, people most

often drove motorcycles. In 1955,

however, there appeared the Zastava

750, popularly called “Fićo”, “Fića”

or “Fičko”, the first Yugoslav

passenger car and the first product

of cooperation between the Zastava

factory in Kragujevac and the

Italian Fiat, which were to roll

down down the assembly line for 30

years. The importance of this first

car in the country's motorisation

was not even overshadowed by

Zastava's later basic models:

Zastava 101 or “Stojadin” produced

in 1970, or Jugo 45 produced in

1980. While the price of more

expensive Western car models was

equivalent to 40 or more average

monthly salaries, a Fića and

Stojadin cost 13 and 20 monthly

salaries respectively in 1971.

However, money was found and the

country embarked on a fast

motorization process in which the

car was becoming a status symbol. In

1970, one newspaper printed a

photograph of a man from Sandžak

with his car in front of a

dilapidated shack after deciding to

invest money first in a Fića and

then in his home. It was also

written about the residents of a

Macedonian village on Mount Šar who

kept their forty or so cars in the

neighbouring town of Tetovo because

their village had no connection to a

road. In 1972, butcher Štef Galović

told journalists that owning a car

was not a luxury; it was his right

after so many years of service. Many

people were guided by precisely this

principle. In 1961, there were as

many as 238 Yugoslavs per passenger

car, 10 years later – 24 and in the

late 1980s – seven on average; in

Kosovo there were as many as 23

persons per passenger car and only

four in Slovenia. After being

considered a luxury, owning a car

was gradually becoming the sign of a

common standard of living. However,

it was still viewed as a striking

consumption item and the most

expensive asset kept outside one's

safe home. It enjoyed the status of

a pet or family member, so that it

could often be found on family

photographs. A car was treated with

personal or family pride. Its owner

purchased accessories for it, its

engine was maintained and its body

was polished. In return, it

faithfully served its owners,

helping them to carry out everyday

tasks, whose pace and success were

becoming increasingly dependent just

on it, as well as to conquer new

spaces during excursions and

travels. Thus, it was becoming the

symbol of freedom because one could

travel by car almost everywhere at

any time, regardless of public

transport lines and timetables.

Simply enjoying the ride became part

of everyday life.

The Rise of Tourism

If the culture of

travel had not taken hold, such

rides would not have been possible.

At the time of the formation of the

first Yugoslav state there already

existed a good basis for the

development of domestic tourism. It

included the Adriatic coast, spas in

the interior of the country and

regions with a tradition of

mountaineering clubs and chalets. In

1923, the Putnik Travel Agency was

established as a joint-stock company

with the aim of “preparing travel

programs and organizing tours,

instructional people's and other

tourist travel within the country

and abroad”. Four years later, it

became a state-owned company and, as

such, it restored its operations

after the Second World War. A number

of independent travel agencies

sprang up from this first seed.

Tourism did not occupy a special

place in the inter-war economy and

everyday life. During the 1930s,

Yugoslavia was visited by about

900,000 tourists, spending about

five million nights each year. In

the years preceding the Second World

War, domestic tourists constituted

the majority, while one fourth were

foreign tourists, mostly Germans and

then Czechoslovaks, Hungarians,

Italians, Britons and Austrians.

Domestic tourists included

middle-to-upper class

holiday-makers, while the other

urban population would stick to

urban resorts, and seaside and

freshwater bathing areas. In the

1920s, the sun-tanned body became

the symbol of health and well-being.

Otherwise, bathing and wearing a

swimming suit in public were not

easily accepted by the older

generations. A defining moment for

the popularisation of tourism was a

new approach taken by socialist

Yugoslavia by introducing paid

annual leave and social tourism. The

general workers’ right to annual

leave for two to four weeks was

introduced in 1946. Going on holiday

was understood as an essential part

of the standard of living and the

right of the entire population.

Social tourism anticipated

preferential accommodation and

transport rates, a holiday bonus,

and workers', children's and youth

holiday homes. Despite some remarks,

many workers were satisfied:

“Workers' holiday homes are cheaper

and make you feel more relaxed

because around here there are mostly

your friends and acquaintances. It

is more comfortable than being with

unknown people. In addition,

everything is organised, so that I

don't have to think about anything.

So you can spend comfortable and

really carefree holidays.”

In the mid-20th

century, many people traveled and

saw the sea for the first time. The

sea was the main holiday

destination. Fascination with the

sea was a frequent theme in popular

songs and media, which regularly

reported on the holidays of workers

and domestic film, music and sports

stars. One of many similar

statements published in the domestic

press was: “My most favourite

encounter is with our blue Adriatic

coast and I feel best when I swim.”

Thanks to large investments, tourism

grew rapidly until the record year

of 1986 when over 111 million

tourist nights were realised.

According to their share of tourist

nights, most domestic and foreign

guests came from West Germany,

Serbia, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia

and Herzegovina, the United Kingdom,

Austria and Italy. The surveys

showed that during the period of

late socialism every second citizen

travelled somewhere on annual leave.

These were mainly smaller families,

better educated, with a higher

income, and a permanent address in

one of the larger cities in the

interior of the country. Commercial

and foreign tourism grew stronger

during the 1960s when the country

opened up to the West and when the

importance of foreign exchange

earnings from tourism was

recognized. The proliferation of

beds at private accommodation

facilities and an increasing number

of family houses exhibiting the sign

“Zimmer frei” pointed to the change

brought by tourism to the local

population, especially on the

Adriatic coast mostly in Croatia.

With their consumer goods, behaviour

and customs, foreign guests brought

their hosts closer to the

contemporary West, while

well-appointed beaches, sports

grounds, swimming pools, hotel

restaurants and congress halls found

a public purpose throughout the

year.

In contrast to

annual leave, the weekend had to

wait to fulfil its complete role of

weekly rest until 1965 when the

working week was shortened to 42

hours by law. For most workplaces

this implied five 8-hour working

days and one working Saturday per

month, or working extra two hours

once a week. A weekend was often

extended by one or more adjacent

non-working state holidays. In 1967,

every fifth citizen of Zagreb would

go on a hal-day or full-day

excursion, while in the early 1980s

every third Yugoslav used to go on

weekend excursions, at least

occasionally. People were most often

forced to stay at home due to the

lack of money or time or the habit

or need to spend their leisure time

in this way. Weekends were

inevitably associated with weekend

cottages, whose building began in

the 1950s. By the 1980s this

practice had spread among different

strata of the population. These

cottages were mostly built in the

vicinity of large cities and

industrial centres where they really

served for spending short weekly

holidays, breathing fresh, clean air

and having a barbecue. For many

people it was important to have a

summer cottage at the seaside: “We

live here 'on our own terms'. „It's

simply different from being a

tourist. It gives you a different

feeling, a different attitude. You

feel comfortable and free […] You

live life on your own terms.”

In the Rhythm of the Century

Apart from

excursions and travels during this

century, popular culture was also

increasingly penetrating leisure

time, promoted by thousands of

daily, weekly and monthly

newspapers, as well as programs

broadcast by radio stations (Radio

Zagreb since 1926, Radio Ljubljana

since 1928 and Radio Belgrade since

1929) and television stations (TV

Zagreb since 1956, and TV Belgrade

and TV Ljubljana since 1958).

Foreign radio and television

programs were also popular. Cinemas

showed domestic, Hollywood and other

foreign blockbusters; record

companies were producing records and

cassettes featuring domestic and

foreign artists; and publishing

companies were printing literary

works by domestic authors as well as

translated works by foreign ones.

Apart from actors, singers and

authors, star status was also

enjoyed by athletes. Sports events

were watched live or through the

media. Apart from professional

sports, amateur sports were also

developed, especially in the second

Yugoslavia. Young people socialized

with each other in the open, in city

centres, dance halls and, finally,

discotheques, turning evenings-out

into nights-out and behaving in

accordance with the selected

subculture. From the 1960s onwards,

leisure time was increasingly

occupied by various hobbies, which

reflected various life styles and

were an increasingly important

determinant of identity.

In 1938, the basic

living costs per person amounted to

630 dinars each month or, more

precisely, 1,500 dinars for an

average worker's family consisting

of 2.4 members. However, half of all

workers earned less than the amount

needed for only one person. So there

was enormous dissatisfaction and

strikes were frequent. In the 1920s,

the share of food costs in the

living costs of a four-member family

in Zagreb amounted to about 40

percent. In the second half of the

century, at the country level, a

worker's four-member family had to

earmark about 50 percent of its

income for food, which still

represented a high share. The lowest

share, about 40 percent, was

recorded in the late 1970s when the

standard of living and purchasing

power were at their highest level.

In 1978, the average salary was

5,075 dinars, ranging from 4,084 in

Kosovo to 5,903 Slovenia. If the

consumer basket contained 1 kg of

bread, 1 kg of sugar, 1 kg of beef,

1 kg of apples, 1 l of milk, an egg,

a pair of men's shoes, a haircut and

a movie ticket, it turned out that

in 1978 the average salary could

cover the cost of 8.4 baskets. Due

to a drop in the standard of living

ten years later, the salary could

cover the cost of 5.7 baskets; in

1968 – exactly 8; in 1958 – 4.2 and

in the pre-war year 1938 – only 3.8.

This simplified example shows that

in the late 1960s the average

purchasing power was about double

that of the pre-war year, and it

went on increasing until 1978, when

it reached highest level in the

history of Yugoslavia. This picture

of the increase in the standard of

living will become more complete if

one takes into account the achieved

level of tehnological development,

high health and hygiene standards

and higher educational level of the

population. Should the question of

progress be posed from the aspect of

everyday life, it would be reflected

in the wish for electricity, paved

roads, a comfortable apartment or

house, a marriage of love and not an

arranged marriage, fertile land, job

security, as well as the wish for

the children to be better off in the

future. It is precisely these issues

that are conversation topics in the

prize-winning feature film Train

Without a Timetable (Veljko Bulajić,

1959): “There is also electricity

and a state road over there, and you

can have a radio in the house. It

can play and sing for you all day

long! Just like in a dream...“ This

dream was part of the changes

brought by the 20th century to

everyday life, including increased

opportunities and needs. Yugoslavia

was attuning the rhythm of the

century to its own development level

and political priorities.

Selected Bibliography

1.

Adrić, Iris et al. (ed.), Leksikon

YU mitologije, Postscriptum i Rende,

Zagreb and Belgrade, 2004.

2.

Bilandžić, Dušan, Historija

Socijalističke Federativne Republike

Jugoslavije. Glavni procesi

1918-1985, Školska knjiga, Zagreb,

1985.

3.

Dijanić, Dijana, Mirka

Merunka-Golubić, Iva Niemčić, Dijana

Stanić, Ženski biografski leksikon.

Sjećanje žena na život u

socijalizmu, Center for Women's

Studies, Zagreb, 2004.

4.

Dobrivojević, Ivana, Selo i grad.

Transformacija agrarnog društva

Srbije 1945-1955., Institute for

Contemporary History, Belgrade,

2013.

5.

Duda, Igor, U potrazi za

blagostanjem. O povijesti dokolice i

potrošačkog društva u Hrvatskoj

1950-ih i 1960-ih, Srednja Europa,

Zagreb, 2005.

6.

Duda, Igor, Pronađeno blagostanje.

Svakodnevni život i potrošačka

kultura u Hrvatskoj 1970-ih i

1980-ih, Srednja Europa, Zagreb,

2010.

7.

Grandits, Hannes, Karin Taylor

(eds.), Yugoslavia's Sunny Side. A

History of Tourism in Socialism

(1950s-1980s), Central European

University Press, Budapest – New

York, 2010. / Sunčana strana

Jugoslavije. Povijest turizma u

socijalizmu, Srednja Europa, Zagreb,

2013.

8.

Janjetović, Zoran, Od internacionale

do komercijale. Popularna kultura u

Jugoslaviji 1945-1991., Institute

for Recent History of Serbia,

Belgrade, 2011.

9.

Kolar Dimitrijević, Mira, Radni

slojevi Zagreba od 1918. do 1931.,

Institute for the History of the

Workers' Movement of Croatia,

Zagreb, 1973.

10.

Luthar, Breda, Maruša Pušnik (eds.),

Remembering Utopia. The Culture of

Everyday Life in Socialist

Yugoslavia, New Academia Publishing,

Washington, 2010.

11.

Marković, Predrag J., Beograd između

Istoka i Zapada 1948-1955., Službeni

list, Belgrade, 1996.

12.

Marković, Predrag J., Trajnost i

promena. Društvena istorija

socijalističke i postsocijalističke

svakodnevnice u Jugoslaviji i

Srbiji, Službeni glasnik, Belgrade,

2012.

13.

Panić, Ana (ed.), Nikad im bolje

nije bilo? Modernizacija

svakodnevnog života u

socijalističkoj Jugoslaviji, Muzej

istorije Jugoslavije, Beograd, 2014.

/ They Never Had It Better?

Modernization of Everyday Life in

Socialist Yugoslavia, Museum of

Yugoslav History, Belgrade, 2014.

14.

Patterson, Patrick Hyder, Bought and

Sold. Living and Losing the Good

Life in Socialist Yugoslavia,

Cornell University Press, Ithaca,

London, 2011.

15.

Petranović, Branko, Istorija

Jugoslavije 1918-1988., Nolit,

Belgrade, 1988.

16.

Rihtman-Auguštin, Dunja, Etnologija

naše svakodnevice, Školska knjiga,

Zagreb, 1988.

17.

Ristović, Milan (ed.), Privatni

život kod Srba u dvadesetom veku,

Clio, Belgrade, 2007.

18.

Senjković, Reana, Izgubljeno u

prijenosu. Pop iskustvo soc kulture,

Institute of Ethnology and Folklore,

Zagreb, 2008.

19.

Sklevicky, Lydia (prir. Dunja

Rihtman-Auguštin), Konji, žene,

ratovi, Ženska infoteka, Zagreb,

1996.

20.

Šuvar, Stipe, Sociološki presjek

jugoslavenskog društva, Školska

knjiga, Zagreb, 1970.

21.

Vučetić, Radina, Koka-kola

socijalizam. Amerikanizacija

jugoslovenske popularne kulture

šezdesetih godina XX veka, Službeni

glasnik, Belgrade, 2012.

|