|

Case

study

1

Introduction

Very often the

argument for the massive use of rape

as a weapon during the war in

Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1990s is based

on Balkans’ assumingly violent

sexual character of the society,

patriarchally organized and ruled,

what throughout the history visibly

marked the roles of both, women and

men, and somehow implied their

positions as ‘victims’ for the first

and/or ‘perpetrators’ for the second

during the combat. Historiography of

‘ethnosexualities’3 and the constant

presence of violence as one of its

significant components are very

illustrative in these terms. With

analyzing the past production of the

knowledge in the field, we came to

understanding of sexualities that

are being under investigated beyond

the representations that cover its

‘savage’ and ‘primitive’

characteristics. In this text,

therefore, I suggest reading those

ethnosexualities in terms of

Todorova’s ‘balkanism’ paradigm:

very same ideas as used and

critically positioned in her book

‘Imagining Balkans’ (1997) can be

applied specifically to the

development of the idea of ‘Balkan

sexuality’: throughout the history,

we can read on primitivism and

roughness, usually with no

consensual agreement, rather some

sadistic practices, but all governed

and directed by the system of

patriarchy. Most of the early

sources, including the rich

ethnographical contribution of the

travel literature from British,

German and American explorers (see

in: Bracewell and Drace-Francis,

2009) introduces the sexuality along

to other ‘balkanistic’ images as

“notoriously ill-defined”

(Bracewelle 2009, 1) “savage Europe”

and ”land of discord” (Bracewelle,

ibid).

Being interested

in the narratives and

representations of sexuality in the

context of war-rapes that happened

with the dissolution of Yugoslavia

and during the war in 90s, I claim

that those historically determined

ethnosexualites offered a strong

base for the ‘natural’ continuation

of further representations of

sexualities and also sexual and

gender relationships understood only

or primarily through rapes and

massive sexual violence against

women. Not only in the Balkans, but

on a global level, research into

sexuality has presented several

methodological and epistemological

obstacles, not only because there is

no concrete and reliable approach in

measuring sexuality, but also

because sex lives are a private

matter in most cultures, so

researching it can result in

rejection, observed flirtation, or

other emotional responses from the

research participants (Moore 2002).

Since the beginning of the original

research into sexuality in the late

50s in the USA4 (see for instance:

Kinsey, Pomeroy & Martin 1948), the

findings have been based on the

assumption that the respondents can

and will accurately indicate their

attitudes, understandings, and

experiences (see for more:

Tourangeau, Rips and Rasinski 2000);

however, their reporting depends on

memory, self-imagination, and the

influence of socialization processes

around sexuality (Sudman, Bradburn

and Schwartz 1996). Keeping this in

mind, we have to approach to the

historiography of sexuality and the

present day narratives with the

awareness that only certain sexual

behaviors are recorded; perhaps

those most culturally acceptable or

desired; there is rare evidence on

what could we call ‘alternative

sexuality’, namely every other

practice but heterosexual and

reproduction-oriented. Any gay and

lesbian experiences, polyamory or

even the phenomena of sworn virgins,

just to mention the few, were almost

completely overlooked and/or denied.

Deeply rooted cultural taboos,

shunning, silencing and (individual)

denial all helped to prevent these

alternative practices to be visible,

accepted, and hence to be recorded

in history. Not investigating them

actually helped with their

marginalization further and proving

them inexistent. Being interested

in the narratives and

representations of sexuality in the

context of war-rapes that happened

with the dissolution of Yugoslavia

and during the war in 90s, I claim

that those historically determined

ethnosexualites offered a strong

base for the ‘natural’ continuation

of further representations of

sexualities and also sexual and

gender relationships understood only

or primarily through rapes and

massive sexual violence against

women. Not only in the Balkans, but

on a global level, research into

sexuality has presented several

methodological and epistemological

obstacles, not only because there is

no concrete and reliable approach in

measuring sexuality, but also

because sex lives are a private

matter in most cultures, so

researching it can result in

rejection, observed flirtation, or

other emotional responses from the

research participants (Moore 2002).

Since the beginning of the original

research into sexuality in the late

50s in the USA4 (see for instance:

Kinsey, Pomeroy & Martin 1948), the

findings have been based on the

assumption that the respondents can

and will accurately indicate their

attitudes, understandings, and

experiences (see for more:

Tourangeau, Rips and Rasinski 2000);

however, their reporting depends on

memory, self-imagination, and the

influence of socialization processes

around sexuality (Sudman, Bradburn

and Schwartz 1996). Keeping this in

mind, we have to approach to the

historiography of sexuality and the

present day narratives with the

awareness that only certain sexual

behaviors are recorded; perhaps

those most culturally acceptable or

desired; there is rare evidence on

what could we call ‘alternative

sexuality’, namely every other

practice but heterosexual and

reproduction-oriented. Any gay and

lesbian experiences, polyamory or

even the phenomena of sworn virgins,

just to mention the few, were almost

completely overlooked and/or denied.

Deeply rooted cultural taboos,

shunning, silencing and (individual)

denial all helped to prevent these

alternative practices to be visible,

accepted, and hence to be recorded

in history. Not investigating them

actually helped with their

marginalization further and proving

them inexistent.

On the other hand,

violence in the context of sex seems

omnipresent and attracting many.

With the following text, using the

historiography as the main research

method, I want to provide

theory-grounded historical evidence

to show the continuous reproduction

of this specific narrative that

successfully formed what I later

call ‘balkanism’ of sexual behavior

in the Balkans. Those ideas were,

furthermore, used and reproduced by

several authors while trying to

understand, explain and ground their

arguments of war-rapes incidents

that happened with dissolution of

Tito’s Yugoslavia and the civil war.

Time-wise,

collected sources and my analysis go

back to Ottoman and Byzantine Empire

and geographically, I tried to

narrow it down to the region which

today is Bosnia-Herzegovina. War

rapes that happened there resonated

in international community more than

any other debate on sexuality in

this region and this narrative may

very easily overshadow all other

interest in researching sexuality

after the war, especially beyond the

sexual violence and the legacy of

the war crimes. This epistemological

angle seems interesting to be

included as a comparative analysis

with the historical sources. By

unveiling the tendencies toward the

balkanistic discourse in documenting

sexual practices through historical

perspective, I aim to show the

danger of ‘normalizing’ rapes and

the ascribed essentialism of

violence in sexuality with the help

of this same historic evidence. This

narrative practice in many cases

supported to perceive and understand

the war rapes in Bosnia-Herzegovina

as a part of ‘cultural heritage’,

some sort of an accepted cultural

meme, that is hard to be uprooted.

More generally, the

violence-emphasizing historical

evidence helps to keep the

narratives on sexuality further in

the frames of balkanistic discourse,

what on an educational level and

other practices of constructive

dealing with the violent past

prevents us to see them beyond

heteronormative,

patriarchally-submissive and violent

practices. This, from a discursive

level can later successfully

translate into the living

experiences and therefore slows down

any other practices of ‘alternative

sexualities’ to be culturally

accepted and as well respected.

Origins and Creations of the

Balkan(istic) Sexuality

Historically-wise,

the region of Balkans is not

specific or ‘different’ in how local

sexual culture is stigmatized,

regulated and mythicized and how its

cultural connotations and

applications evolved over decades.

The vast majority of available past

studies refer to patriarchal,

male-supremacist ideologies, ruling

intimate relationships in the

Balkans and by some rare exceptions

there is no other than

heteronormative discourse in

sexuality, that is reproductive

sexuality.

Rape as a part of

some marriage rituals and as a usual

marital praxis in southeastern

Europe has been recorded in several

studies, and there is substantial

data particularly on marital rape

and rape practices under the

Byzantine and Ottoman Empire (Levin

1989; Buturović and Schick 2007).

However, we have to be careful with

the very definition of rape since

today we operate with the modern

concept or understanding of rape as

a crime. In the context of the

Medieval Slavs, Levin (1989, 212)

notes that rape constituted an

insult to the family’s honor and was

a violation of public morality

(Levin 1989, 245) the acceptance of

violence by superior (men) against

inferior women. “In these societies

as in any other that authorizes

violence and subordinate women to

men, rapes were bound to occur”

(Levin 1989, 246). Besides, rape was

considered appropriate retaliation

when a woman did not “conduct

herself in a manner appropriate to

her place in the society – if she

insulted men, for instance, or got

drunk (Levin 1989, 245). Rape was a

violent act of social control rather

than an expression of certain

sexuality; medieval Slavic would

live by Christian standards, where

the motivation against marital rape

was not found in the protection of a

woman’s dignity, but was promoted in

Slavic belief that lust was improper

and should not be encouraged (Levin

1989, 243). Throughout history, a

woman’s body has been labeled and

stigmatized by her presumed

“inclination to tempt men sexually,

so she was considered sinful and

impure” (Djajić Horvath 2011, 381).

Hence, women symbolized the family’s

code of honor and shame, as evident

in the highly controlled aspects of

their chastity, marital virtue, and

fertility; and they were primarily

valued as wives and mothers (Olujić

1998). There are several recordings

of a historical continuum of the

public’s perception of rape victims

and the loss of their integrity,

honor, and shame (for instance Levin

1989, 227). In many cases of rape,

death might be preferable (and

usually the dishonor of the victims

is express by this) (Levin 1989,

227). Rape as a part of

some marriage rituals and as a usual

marital praxis in southeastern

Europe has been recorded in several

studies, and there is substantial

data particularly on marital rape

and rape practices under the

Byzantine and Ottoman Empire (Levin

1989; Buturović and Schick 2007).

However, we have to be careful with

the very definition of rape since

today we operate with the modern

concept or understanding of rape as

a crime. In the context of the

Medieval Slavs, Levin (1989, 212)

notes that rape constituted an

insult to the family’s honor and was

a violation of public morality

(Levin 1989, 245) the acceptance of

violence by superior (men) against

inferior women. “In these societies

as in any other that authorizes

violence and subordinate women to

men, rapes were bound to occur”

(Levin 1989, 246). Besides, rape was

considered appropriate retaliation

when a woman did not “conduct

herself in a manner appropriate to

her place in the society – if she

insulted men, for instance, or got

drunk (Levin 1989, 245). Rape was a

violent act of social control rather

than an expression of certain

sexuality; medieval Slavic would

live by Christian standards, where

the motivation against marital rape

was not found in the protection of a

woman’s dignity, but was promoted in

Slavic belief that lust was improper

and should not be encouraged (Levin

1989, 243). Throughout history, a

woman’s body has been labeled and

stigmatized by her presumed

“inclination to tempt men sexually,

so she was considered sinful and

impure” (Djajić Horvath 2011, 381).

Hence, women symbolized the family’s

code of honor and shame, as evident

in the highly controlled aspects of

their chastity, marital virtue, and

fertility; and they were primarily

valued as wives and mothers (Olujić

1998). There are several recordings

of a historical continuum of the

public’s perception of rape victims

and the loss of their integrity,

honor, and shame (for instance Levin

1989, 227). In many cases of rape,

death might be preferable (and

usually the dishonor of the victims

is express by this) (Levin 1989,

227).

Women as

possessions and repressive control

over women’s sexuality in the rural

and pre-modern Balkans are noted by

Denich (1974) and Durham (1928).

Distrust of female sexuality before

marriage is illustrated by the

custom of publicly demonstrating the

woman’s proof of virginity after the

wedding night; however, virgin blood

as respected and appreciated clearly

opposes to menstrual blood as

unclean (Olujić 1998, 36). Several

instructions of self-violence,

associated with shameful and

dishonored behavior of young teenage

girls, writes Olujić “demonstrate

the extent to which women are

expected to keep themselves in

control and avoid men's public

control over them.” (Olujić 1998,

36). Denich (1974, 254) writes about

two components to the control of

women’s sexuality: “one practical,

the other symbolic” (ibid):

On the practical side the tenuous

bond between a woman and her

husband’s household would be further

undermined by liaisons with other

men. However, the more significant

dimension of the severity of

measures for sexual control over

women stems from the symbolic

importance of sex in the competitive

social environment situation in

which agnatic groups exist. The

ability of a household’s men to

control its women is one of many

indicators of its strength;

accordingly, evidence of lack of

control over women would indicate

weakness and possibly reveal the

men’s vulnerability to other

external challenges (Denich 1974,

254-55)

In all of these

societies women not behaving in the

properly submissive manner5 (emphasis

added) are liable to a beating from

their husbands (Denich 1974, 255);

the severity of these sanctions

express the collective dominance of

the agnatic household, rather than

simply that of the individual

husband over their wife (Denich

1974, 225).

By the end of the

First World War the Balkan men were

associated with a brutal sexuality,

whereas Northern Europeans (...)

were represented as being capable of

more complex psychological and

erotic responses (Bjelić and Cole

2002, 286). The Slav appears to

exercise 'natural' violent impulses,

which ‘civilized’ soldier resist,

sublimate, or displace (Bjelić and

Cole 2002, 284). All men, according

to Hirschfeld (1941, 321), are

potential rapists, but those of

‘advanced’ civilizations mostly

fantasize or threat by rape. “Slav

is sexualized,” writes Bjelić and

Cole (2002, 285) and in so doing,

“marks himself as part of an

inferior race” (ibid). The Balkans

as ‘primitive people’, and thus

sexualized, were described in

several early ethnographic studies

(see in Bjelić and Cole 2002, 280);

while the ‘Turks’ or the ‘Orientals’

are associated with sensuality,

sexuality, and the feminine,

Southern Slavs (usually referring to

people affiliated to Orthodox or

Catholic Christianity) are

associated with primitiveness,

roughness, and violence. Hirschfeld

(1941, 310) writes about the

differences among the ‘perversive’

sexual culture of ‘Turkos’ that

leaned toward bodily mutilation, and

on the other side among “the South

Slavs, where sadistic murders,

castrations, and rapes were very

frequent.” This division of the two

prevailing definitions of

ethnosexuality and their historical

development has played a major role

in the national mythology and

symbology used, besides the torture

and atrocities in the war in the

90s.6

Jovan Marić, for

instance, in his essentialistic book

What kind of people are we Serbs?

Contribution to the Characterology

of the Serbs (1998) outlines the

Serbs efficiently and notes that

successfulness is due to their

assumed sexual performances in which

Serbs “are in a good standing”

(Marić 1998, 169) with their

inherited ‘Slav virility’. With

regards to the historically based

hatred legacy among the Turks and

the South Slavs, and the mythology

used for revenge, it is nothing but

a great paradox that Marić refers to

the Turks as those from whom the

Serbs inherited their sexual

prowess. However, this ethnicized

representation of sexuality and the

“genetic source of Serbian virility”

(Bjelić and Cole 2002, 291) served

as a great ideological fuel in peer

supporting for mass rapes committed

during the war. Jovan Marić, for

instance, in his essentialistic book

What kind of people are we Serbs?

Contribution to the Characterology

of the Serbs (1998) outlines the

Serbs efficiently and notes that

successfulness is due to their

assumed sexual performances in which

Serbs “are in a good standing”

(Marić 1998, 169) with their

inherited ‘Slav virility’. With

regards to the historically based

hatred legacy among the Turks and

the South Slavs, and the mythology

used for revenge, it is nothing but

a great paradox that Marić refers to

the Turks as those from whom the

Serbs inherited their sexual

prowess. However, this ethnicized

representation of sexuality and the

“genetic source of Serbian virility”

(Bjelić and Cole 2002, 291) served

as a great ideological fuel in peer

supporting for mass rapes committed

during the war.

According to The

Sexual History of World War, written

by Magnus Hirschfeld in 1941, the

war in the Balkans has always been

an “extension of the ‘erotic

process’,” writes (Hirschfeld 1941),

whereby suppressed egos produce

‘destructive sadistic powers’ during

wartime, the sexual misery of

peacetime, the hypocritical morality

of the ruling classes, the perverts,

the natural impulses, and finally

outbursts in aberrant reactions

(Hirschfeld 1941). His ‘chronicle’

of wartime perversities and sexual

deviations is intended to “mature

educated persons only” and includes

essays on prostitution, female

spies, the “eroticism behind

military drills,” “the

bestialization of men,” “sadism,

rape, and other atrocities.”

Hirschfeld links deviant sexual

practices within his theory of

cultural development and claims that

“individual acts of cruelty, often

with definite erotic casts” were

executed “principally by the more

primitive groups” (Hirschfeld 1941,

308). He bases his conclusion on

both pejorative and balkanistic

perspectives, where “these people

/Balkan Slavs/ have remained behind

the rest of Europe in civilization

and have retained their primitive

traditions (Hirschfeld 1941, ibid).”

It clearly supports Alexandra Djajić

Horvath’s argument, claiming that

“the progress of a nation is

‘measured’ by the treatment of its

women” (2011, 369).

Hirschfeld

believes in prostitution as a

solving source in the prevention of

wartime rape; in his vision, wartime

rape happens because of alcohol,

“protracted sexual abstinence” and

the image of war as a “sexual

stimulant,” but its occurrence could

be cut down by assuring that there

are prostitutes and brothels for the

warriors: “The field- and halting

station brothels, no matter how

disgusting, diminished the number of

cases of rape during the war

(Hirschfeld 1941, 321).” Assuming

that one type of violence would be

solved by another one, expresses his

arrogant and sexist, if not

misogynistic, image of women's

sexuality:

For the women, the brutality and

aggressiveness of the man is, to a

certain degree, accompanied by

pleasure. The reasons for this are

obvious. The conquest of woman and

the act of copulation, presupposes,

on the men's part, a definite joy in

attacking. (...) The normal woman

desires to be conquered by the man,

to be forced; and only one step

separates her from the female

masochist who wishes, not only to be

overwhelmed, but also to be raped

and brutalized (Hirschfeld 1941,

ibid).

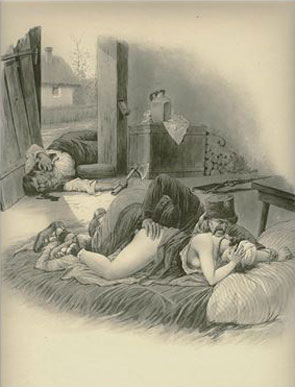

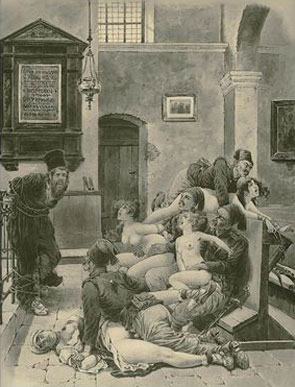

Another such

controversial depiction of the

‘cruel’ and ‘primitive’ Balkans

sexuality appeared in a political

and pornographic pamphlet entitled

Balkangreuel, published in 1909.7

Balkangreuel contained twelve

lithographs with explicit depictions

of sex, and not just any sex: the

main narrative leads to the brutal

rape of Christian virgins by Turkish

invaders, conquering the Balkan

territories. As an introduction to

these paintings, a five-page long

text describes the Balkans as a

historically known place of wild,

ethnically mixed, and brutally

violent people (Schick 2007, 292).

Particularly one of the paintings

(Figure no. 2) contains a scene of

four Turkish soldiers raping four

young maidens inside an Orthodox

church, as the priest is forced to

watch.8 There are others showing

violent sexual acts, usually in the

household. While the women are

naked, the men are dressed in

traditional Turkish clothes. Some

pictures depict local men killed on

the floor, while the women are being

raped by the Turkish man (Figure

no.1). Again, according to the

testimonies, the tales of the Balkan

maidens and the Turkish ravishers

played an important role during the

conflicts in Yugoslavia in the early

1990s.

Figure 1 & 2

Source: Sieben,

2014.

Notions on the

sexuality behaviors in the Balkans

can be found in some popular

culture, music, songs, movies,

stories, and in some ethnographical

studies (see Knežević 1996).

Knežević outlines a Croatian form of

epic singing called Ganga that

usually communicates messages of

love, betrayal, desire, and the sex

appeal of young women and men. In

its symbolism, a ‘plowing’ as

intercourse, a cluster of wool as

the vagina and a rifle as the penis,

can be found (Olujić 1998, 34). In

the post-war rapes/sexual abuse

oriented narrations, the rifle as a

penis or the penis as weapon in

general has become one of the

leading motifs (see in Stiglamayer,

1994). Ganga songs portray the rural

communities’ understandings of

womanhood, the sexuality of women,

and virility:

Men portray

themselves as wanting sex and

portray women as withholding it; men

depict women as hypocritical objects

and depict themselves as powerful

subjects. (…) In ganga, men express

their view of women as sexual

objects through symbolic language

(Olujić 1998, 35)

Although, there are rare records of

women expressing their sexuality

through ganga songs, Brandes (1980)

notes that some forms of folklore

can be found that hold the idea of

women as secretly and ardently

sexual. The tight control over

women's sexuality all over

southeastern European cultures is

evident through honor/shame

binaries, where women represent the

code of honor of the family and/or

the code of shame:

For women, honor and shame are the

basis of morality and underpin the

three-tiered hierarchy of statuses:

husband, family, and village. In the

former Yugoslavia, these traditional

values regarding sexual behavior,

which condoned rape through

honor/shame constraints, took

precedence over economic

transformations, state policy

commitments under communism, and

male migration (Olujić 1998, 34).

Olujić describes another rather

violent practice of men, expressing

their right over women sexuality.

After World War II, ‘chasing’ (orig.

gonjanje) has become a common

practice in rural spaces around

Balkans. In this ‘game’

male teenagers would run after a

woman, knock her down, jump on top

of her, pin her onto the floor, roll

her over, and then pinch her breasts

or grab at her genital region. In

public, this physical assault

aroused the cheers of men and

motivated women to yell out and pull

the man off the victim. Since the

attacked women usually rejected the

men's advances, the play rape became

a way for a man to publicly save

face and publicly humiliate a woman

for rejecting him. In short, it was

a game of status in which men had to

be on top (Olujić 1998, 9).

Her informants who were all male but

from different generations, share

the stories of ‘competitive games’

and ‘measuring the sexuality.’ Both

employ various forms of public

displays of virility or sexual

prowess. As an example, she mentions

public boastings about men’s sexual

affairs, the furthest ejaculations

and the longest penis competitions

(Olujić 1998, 36). Secretly seeing a

naked woman, her bare breasts and

pubic hair in particular was one of

the most important desires to be

accomplished among young and

unmarried men (ibid). Women’s past

sexual experiences were also a

subject of measurement: according to

Olujić’s informants, men were able

to recognize a virgin without

sleeping with a woman:

One way to ‘measure’ her chastity

was to assess her breasts: If she

had soft breasts (meka sisa), in

other words, if they were ‘hanging’,

it meant that someone else already

perforated her (probusit). Another

way to decipher whether or not a

woman was a virgin was to secretly

listen to the sound of her flowing

urine. If she ‘pissed wide’ (siroko

pisa), it meant that she had been

pierced (probijena) (Olujić 1998,

36).

In Tito’s Yugoslavia women were

still valued primarily as mothers

and workers (Denich 1974; Stein

Erlich 1966); despite the

liberalization of the country, a

generalized patriarchal culture

continued to subordinate women who

were also under the Tito’s rule

(Drakulić 2010). Women became

‘equal’ as a work force, but that

did not change their social

determination toward domestic

responsibilities and child care.

Cockburn (1998) writes about

increased domestic violence as men’s

patriarchal authority was challenged

by women’s empowerment that had come

along with the socialism order.

However, Yugoslavia maintained a

general openness to the outside

world, and “women were free to

travel and read literature from all

over the world, and a small minority

of Yugoslav women joined the new

wave of feminists that surged across

Western Europe in 1970” (Snyder,

Gabbard, May and Zulcic 2006, 188).

Biljana Kašić, a Croatian feminist,

has wrapped the magazine analysis of

‘Yugoslav sexualities’ in expressing

her doubts on the potential of

transforming cultural and

psychological behavior into cultural

innovations or fresh approaches to

sexuality (Kašić 2005, 95).

According to the sexual

representations in magazines,

Yugoslav sexuality was about

“sensationalism, an oversimplified

approach to sexuality, and recipes

for sexual life presented in

extremely bizarre ways (Kašić,

ibid).” Kašić continues: “In those

magazines the very package of

sexuality was quite predictable

(...) heterosexual-oriented

magazines offer a digest prototype

of sexual life with a set of imposed

male sexual fantasies for consumers,

a sort of exoticism of the 'taboos

around sexualities' with images of

the sexy woman as an object” (Kašić

2005, 96). In Tito’s Yugoslavia women were

still valued primarily as mothers

and workers (Denich 1974; Stein

Erlich 1966); despite the

liberalization of the country, a

generalized patriarchal culture

continued to subordinate women who

were also under the Tito’s rule

(Drakulić 2010). Women became

‘equal’ as a work force, but that

did not change their social

determination toward domestic

responsibilities and child care.

Cockburn (1998) writes about

increased domestic violence as men’s

patriarchal authority was challenged

by women’s empowerment that had come

along with the socialism order.

However, Yugoslavia maintained a

general openness to the outside

world, and “women were free to

travel and read literature from all

over the world, and a small minority

of Yugoslav women joined the new

wave of feminists that surged across

Western Europe in 1970” (Snyder,

Gabbard, May and Zulcic 2006, 188).

Biljana Kašić, a Croatian feminist,

has wrapped the magazine analysis of

‘Yugoslav sexualities’ in expressing

her doubts on the potential of

transforming cultural and

psychological behavior into cultural

innovations or fresh approaches to

sexuality (Kašić 2005, 95).

According to the sexual

representations in magazines,

Yugoslav sexuality was about

“sensationalism, an oversimplified

approach to sexuality, and recipes

for sexual life presented in

extremely bizarre ways (Kašić,

ibid).” Kašić continues: “In those

magazines the very package of

sexuality was quite predictable

(...) heterosexual-oriented

magazines offer a digest prototype

of sexual life with a set of imposed

male sexual fantasies for consumers,

a sort of exoticism of the 'taboos

around sexualities' with images of

the sexy woman as an object” (Kašić

2005, 96).

The presence of pornography and

female nudity in Start Magazine,9 one

of the most iconographic soft porn

magazines available on the Yugoslav

market, has become attacked by

Catherine MacKinnon in her

accusation that pornography

influenced the mass rapes during the

war in Bosnia. This single magazine

was enough of an argument for

MacKinnon to frame Balkan sexuality

in pure violence, obviously more

savage, primitive, and tribal than

‘Western sexuality’. “When

pornography is this normal,” she

writes taking into consideration the

case of Start Magazine, “a whole

population of men is primed to

dehumanize women and to enjoy

inflicting assault sexually

(MacKinnon 1994, 77).10 Paradoxically

enough, not only was Start Magazine

highly under the influence of

Western pornography, but Bjelić and

Cole (2002, 292) write how even

after the war, the majority of

late-night pornography is of a

non-Balkan origin; instead the

actors speak French, German, and

English. “Pictures of bare-breasted

women in the daily papers,” they

continue, “are often reprints of

non-Yugoslav actresses and models.”

Videos, modeled on those of MTV,

feature Yugoslav women singing, for

example, a Shania Twayne song,

dressing like Shania Twayne, and

even imitating her body movements.

One could, of course, explain such

borrowings as an effort of

‘globalization’, but our point is

more specific: Whether we like it or

not, pornography is an effect of

modern forms of governmentality, not

its barbaric other (Bjelic and Cole

2002, 292).

Apart from rare ethnographic

research on sexuality in the

Balkans, the literature overview

shows obvious gaps in the knowledge

on the topic. This fact became

disturbing when post-war resources

started to generate ethno-sexual

ideologies based on balkanistic

discourse, provided by historical

sources and indicating the affirmed

‘backwardness and brutality of the

Balkans’ (Helms 2013). Helms (2008)

writes how after the war, images of

violent and backward, but at the

same time drunk and fun-loving male

peasants, have been replaced by

images of victimized women suffering

from male brutality throughout war

and post-war times. According to

Helms (2008, 118) these new

balkanisms “set aside images of

exotic and erotic harems” and an

“emphasis on violence, barbarity,

and victimhood” have become an

indicator of the backwardness and

brutality of “the Balkans.”

Furthermore, in his chapter about

the ‘causes of brutality’ in the

Bosnian war, Paul Parin writes about

his ‘hypothesis’:

My experiences with typical

child-raising practices in rural

families in different areas of

Yugoslavia have led me to a

hypothesis. In these thoroughly

patriarchal families there is much

tenderness and concern for children

but also strictness and severe

corporal punishment. Neither mother

nor father seems to ‘know’ that one

can or should mute the emotions

through reassurance, distracting, or

constant monitoring of emotional

expression. To this I attribute the

open, direct expression of positive

feelings and sexual desires of men

and women from many areas of the

former Yugoslavia. Perhaps the same

thing is true of aggressive deeds:

they happen spontaneously, are

uninhibited, and are often sustained

by sadistic pleasure (Parin 1994,

47).

According to Parin, sexual violence

is primordial to the Balkan’s

cultural socialization and since

“less structure fanatical gangs are

more characteristic of a dissolving

societal structure than of the

Balkans” (ibid). One can agree that

following the symbolic

interactionism social rules are

learned and reinforced through

everyday interaction, and the

socialization as outlined by Parin

is one of them. Hereby, sexuality is

controlled, dichotomized (gendered),

and as such socially constructed

(Foucault 1978); everything we

regard as female or male sexuality,

sexual interaction, sexual violence,

and rape is culturally imposed. But

Parin gets closer to essentializing

a brutal sexual ethnic identity that

was not an isolated case, especially

in post-war literature where

attributing rapists' and

perpetrators' characteristics became

very visible and uncritically

accepted by many authors and help to

visibly construct the images of

‘balkanistic’ sexuality.

From Eternal Victims to Sexual

Predators:

The Narrative of

ethnosexualities during the war in

1990s

During the war in 90s the power

relationship between women and men

become even more important,

especially in terms of ethnic

division; what we follow in the

narratives from this period is not

anymore ‘a man’ that is violent

against ‘woman’. This patriarchally

grounded division is given another,

very important dimension. We no

longer read only about ‘vulnerable’,

‘silenced’, ‘suppressed’ female

sexuality as such. Muslim women,

reportedly the biggest group

affected by systematic rapes (see

in: Helsinki Watch 1993, UNFPA 2010)

collective and imagined community,

became as an archetype of this

sexuality in Balkans.

On the other hand, the Serb men and

their ‘virility’ as praised by Marić

(1998), became the ultimate carriers

of symbols of violent control over

women’s sexuality during the war –

performed mostly, again, through

violent sexual practices, such as

rape and mutilation. Rape,

accompanied by systematic

impregnation was by evidence

(Helsinki Watch 1993, Allen 1996)

coming mostly from the Serbian

military forces, where Muslim women

(passive antagonists) became

subjected to Serb men (active

protagonist) in the process of

“Serbianizing” of the child (Slapšak

2000, 55). Similar ethnosexual

narrative can be find elsewhere:

Salzman, for instance, titled one of

his chapters, “The Serbian

Usurpation of the female body”

(1998).

The intense Western presence in the

war zone (journalists,

humanitarians, scholars) contributed

to the Westernized framework of the

rapes in relation to sexuality.

Susan Brownmiller and Catherine

MacKinnon, with their background in

theories of rape related to

Western-influenced feministic

thought, became two of the most

important and loud voices on the

topic. Their narratives, recited and

referred to in numerous later

(feminists’) texts, have reduced

men's and women's sexuality in

Balkans to the images of 19th

century ‘travelers’ we unveiled

earlier in this texts. Binary of

Muslim female victims and Serbian

male perpetrators have been then

successfully distributed and

established in science discourse on

rapes in Bosnia, and most of the

work kept the relation with the

general connections to understanding

rapes as the extension of patriarchy

by Western feminists (Brownmiller

1994; Seifert 1994; Stiglmayer 1994;

Allen 1996; Skjelsbaek 2006). The

most evidence was based on reporting

rape as war weapon, where the

enemy’s women’s bodies, but in

general, a violation of women’s

sexuality and using it in political

terms thus humiliates and

demoralizes the entire cultural

identity of the assaulted group. In

this context, sexuality of the war

terminology did almost not exist. The intense Western presence in the

war zone (journalists,

humanitarians, scholars) contributed

to the Westernized framework of the

rapes in relation to sexuality.

Susan Brownmiller and Catherine

MacKinnon, with their background in

theories of rape related to

Western-influenced feministic

thought, became two of the most

important and loud voices on the

topic. Their narratives, recited and

referred to in numerous later

(feminists’) texts, have reduced

men's and women's sexuality in

Balkans to the images of 19th

century ‘travelers’ we unveiled

earlier in this texts. Binary of

Muslim female victims and Serbian

male perpetrators have been then

successfully distributed and

established in science discourse on

rapes in Bosnia, and most of the

work kept the relation with the

general connections to understanding

rapes as the extension of patriarchy

by Western feminists (Brownmiller

1994; Seifert 1994; Stiglmayer 1994;

Allen 1996; Skjelsbaek 2006). The

most evidence was based on reporting

rape as war weapon, where the

enemy’s women’s bodies, but in

general, a violation of women’s

sexuality and using it in political

terms thus humiliates and

demoralizes the entire cultural

identity of the assaulted group. In

this context, sexuality of the war

terminology did almost not exist.

Muslim women, therefore, presented a

primal target of rapes and forced

impregnations, and soon became

anonymous representatives of the

victim collective identity (Helms

2013). By the progress of the field

reports and evidence, the literature

on war rapes started to romanticize

Muslim women and particularly their

assumed ‘purity’: “Woman's purity in

Islam and the Muslim patriarchal

culture is not only held sacred, but

is seen as an essential element to

insure the stability of the society

and the culture” (Salzman 1998,

367). In one of the most recognized

editions of these times, titled Mass

Rape: The War against Women in

Bosnia-Herzegovina and edited by

Alexandra Stiglmayer, we can find a

text by Azra Zalihić-Kaurin. A

Muslim Woman (Azra Zalihić Kaurin

(1994, 170-173). It describes

characteristics of Yugoslav Muslim

women and how it was “unthinkable to

see a Muslim woman in a café or at a

private party.” She continues:

(…) the Muslim woman had to remain

intact and go to her marriage with a

pure soul. Only to her husband could

she show her body – an extramarital

affair was inconceivable (…). It was

also a disgrace if a Muslim woman

became pregnant and the father of

her child would not marry her: there

was no greater shame. Young Muslim

women today may wear miniskirts and

have boyfriends, they may study and

work, but they still respect the

commandment of virginity. Marriage

is as self-evident as is a mother’s

responsibility for the education of

her children (Zalihić Kaurin 1994,

172).

This ethnicization of rapes has been

later criticized by Žarkov (2007)

and Helms (2013), in terms of a very

limited image of victimhood,

embracing primarily rural Bosnian

Muslim women. “In the majority of

Western feminist studies,” claimed

Nikolić-Ristanović (2000, 157), “it

is evident that when they say

‘Bosnian women’, they mean Muslim

women only.”

[Rape ]…is about the almost mythical

‘Muslim’ woman, not only because

victims were not just Muslims, but

also because this reinforces the

fundamentalist construction of a new

woman in some circles in Bosnia,

destroys the possibility of the

existence of atheist women, and

confirms a nationally-genetically

determined ‘weakness' - not only

women's weakness. Here we are

definitely dealing with

crypto-racism (Slapšak 2000, 54).

Žarkov problematizes this

‘islamization of rape vicitims’ with

questioning the importance of

women’s background in the context of

their suffering and traumatic

experiencing of rape and sexual

abuse. She asks: “Why would one

assume that rapes would be less

traumatic for non-religious or urban

women? Or for Serb or Croat or other

women who also came from

conservative communities in which

female chastity, marriage, and

motherhood are prized?” (2007,

146).Those narratives used sexuality

by dividing women as good Muslims

and the rest, and additionally

honored traditional/rural over

modernized/urban life. Purposefully

or not, we can observe the

tendencies of further representation

of Balkans in the light of

backwardness and primitivism. In one

woman's testimony (in Vranić 1996,

125), we can read, how women who

have spoken out on rapes are for

sure “city women”, because everybody

else would be ashamed to talk about

these vulgarities (Vranić 1996,

125). “Not all rape survivors,”

writes Helms (2013, 66), “came from

conservative rural communities, nor

were they all religious, or

religious in the same way.” Not only

those narrative overshadowed any

other sexual practices11 but war rapes

and sexual violence; furthermore

they were enforcing the female

victimhood – but in this context

also of very limited and

ethnically/religiously determined

group of women. The post-war

response of Islamic religious bodies

toward women victims of rapes was

protective and patronizing, too.

Women were given the rank of shahid,

an honor given to Muslims who die

defending their faith, country, or

family. “A woman who is raped is not

guilty, but is like a shahid, the

hero who is killed in Allah's path.

It means she is becoming a heroine.

And the child who is born out of

rape is a Muslim and will be

considered as a member of the Muslim

community” (PBS Women, War and Peace

2011).

On the other hand, the vulgarity,

bestiality of (Serb) men,

perpetrators, have been set up by

Catherine MacKinnon’s striking

contribution already in early 90s

with her thesis on the connection

between pornography and the rapes,

as she put the Balkan males’

sexuality (positioned in how they

treat ‘their’ women) on the global

map based on biological and

essentialist assumptions as well as

numbers of simplifications.

Women have never been regarded as

the equals of men in Balkan society

(...) /Women/ are perceived as

"lower" than men, and are expected

to act meek and obedient in their

homes and workplaces. This subtle

and ingrained disrespect of women

paved the way for the mass rapes

that occurred in Bosnia. A man’s

status in Balkan society therefore

became his excuse and weapon for

sexual violence (in Gilboa 2001).

Although, Catherine MacKinnon's

study (1994) of the pornographic

tapes made during the war that we

mentioned earlier, lack clear

evidence and a critical approach,

she kept the role of important

contributor, being cited in numerous

further works (see for instance:

Rejali 1996; Agathangelou 2000;

Skjelsbaek 2012).12 This and similar

accusations place the violent and

abusive sexual scripts13 again as

infinite and primordial to one

community, but as Lewis has argued,

we have to keep in mind that they

are “not simply downloaded verbatim

into individuals. Individuals select

the cultural scenarios that are most

consistent with their own ideas and

experience of sexuality and

incorporate them into their own menu

of sexual acts” (Lewis 2006, 256).

Another similar case is the

novelistic description of the trial

of Dragomir Kunarac, Radomir Kovač

and Zoran Vuković,14 who all pleaded

not guilty, by Slavenka Drakulić.

Witnessing the trial, she commented

on how it must have seemed surreal

for the men because: Although, Catherine MacKinnon's

study (1994) of the pornographic

tapes made during the war that we

mentioned earlier, lack clear

evidence and a critical approach,

she kept the role of important

contributor, being cited in numerous

further works (see for instance:

Rejali 1996; Agathangelou 2000;

Skjelsbaek 2012).12 This and similar

accusations place the violent and

abusive sexual scripts13 again as

infinite and primordial to one

community, but as Lewis has argued,

we have to keep in mind that they

are “not simply downloaded verbatim

into individuals. Individuals select

the cultural scenarios that are most

consistent with their own ideas and

experience of sexuality and

incorporate them into their own menu

of sexual acts” (Lewis 2006, 256).

Another similar case is the

novelistic description of the trial

of Dragomir Kunarac, Radomir Kovač

and Zoran Vuković,14 who all pleaded

not guilty, by Slavenka Drakulić.

Witnessing the trial, she commented

on how it must have seemed surreal

for the men because:

After all, even if they were a bit

rough with the girls, they did not

kill them, and they did not order

them to be killed (...). (...) the

crimes committed by the trio from

Foča do not even look like crimes,

at least not in their eyes. In their

part of the world, men often treat

their own wives as nothing more than

cattle. The man is the boss, the

woman should shut up and obey him,

and it is not unusual for a man to

beat up his wife in order to remind

her of that. Rape? What is rape

anyway? To take a woman when you

want and wherever you want? It is a

man's right, no question, as far as

his wife is concerned (Drakulić

2005, 53).

As we have seen through the

historical analysis of the sexual

scripts and the available sources,

sexuality in Balkans was portrayed

as aggressively manifested, with

sexually disempowered women and men,

unable to control their animalistic

sexual instincts. However, being so

deeply rooted into the cultural

heritage, not necessarily was

sexuality even understood in these

terms. Marital rape, as an example

of this, has recently become

problematized and acknowledged as a

form of sexual violence against

women but on a community, bottom-up

level still accepted as a

conventional sexual practice. It

means that placed back in the

history – was rape in marriage also

defined as violence or just a

violent sexual practice? This

discrepancy of historical

understanding of ‘violent sexuality’

and acceptance of sexuality being

violent has been illustrated by

Seada Vranić’s Breaking the Wall of

Silence interview with the war-rape

survivor:

You know what rape is. You are

married and you know what men do

with women. For years and years, I

heard that it, between men and

women, sex as it is called in modern

times, was the best thing in this

world or the world beyond. My whole

life I worried about not marrying

(…) Unfortunately now, as an old

woman of 50, I grew wise (...) If

the ‘beast’ hadn’t taken my honor I

would forever think wrongly and I

would never know the truth. Now I

know the truth and I also know that

Allah, punishing me with my bad leg,

spared me from the worst. God didn’t

give me the chance to have a baby

but I also did not go through the

pain and suffering to conceive. I

wish I would have never known the

truth and I wish instead that I

would have regretted (not having

sex) for the rest of my life. My

life was not easy, but I was not

ashamed. Now I must lower my head

and look to the ground (Kadira in

Vranić 1996, 130).

Violent imposition of sexual

intercourse by a man on a woman has

throughout history never been so

visibly acknowledged neither

problematized as it became with the

occurrence of mass sexual violence

during the war. Grounded in

culturally accepted violence in

marriage and traditional rules that,

so to say, means that “through

marriage, a woman consents to sexual

relations with her husband and

cannot later refuse him” (Hayden

2008, 28), sexuality and its

symbolism seems almost impossible to

be thought outside of violence.

To sum up, what has been missing in

the “overpowering presence of the

victimized female body in feminist

studies on war” (Žarkov 2007, 15) is

the reopening of the debate on

female and male sexuality, and the

creation of more diversified public

narratives of sexualized violence

and sexuality in order to

“deconstruct masculinist power in

feminine victimization (Heberle

1996, 63). Since 1970, with the

release of Susan Brownmiller’s

Against Our Will, we seem to agree

on the narrative of a naturalized

female body that makes rapes

possible: they are, prior to the

social structures that rape inspires

and supports, rapable. Women are

raped because they are rapable, and

women are rapable because they are

women (Brownmiller 1975, 16). By

this argument, women are marked as

primordially disempowered as “their

bodies, coded as a place of empty

vulnerability” (Henderson 2013,

242). If we combine this with a long

historical heritage where women only

live in a so called ‘economical

sexuality’, rape occurs not only as

unquestionable form of sex but also

impossible to be removed from our

sexual cultures in any time: past,

present and future.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Historical narratives contributed

visibly to the knowledge of

sexuality that we have today and

also how we use them in further

thinking. The huge efforts of mostly

feminist thought on the legal

definition and public recognition of

rape, sexual violence and sexual

autonomy (of women mostly), have for

sure been triggered by the incidents

during the war. Looking back to

historical predispositions helps to

reveal the cultural heritage and

grounds that contributed to rapes on

such massive scale, but are at the

same time on the very edge to offer

nothing but the study of sexuality

in terms of violence. While such

agency was primarily needed for the

legal and psychological requirements

of the survivors, the produced

knowledge on rape does not respond

to the necessity of rape prevention

in future. For that reason the

“deconstructive narrative” (Heberle

1996, 70) should be used in order to

expose the naturalized social truths

about gender, sexuality, and

victimization that are rooted in the

event of sexualized violence and

rapes, and grounded on the history

of (sexual) oppression against

women. We have to give the evolution

time; violence and aggression

embedded in centuries, will not stop

overnight due to the massive

activism and agency on gender issues

after the war.

In studying sexuality in Balkans,

complex concepts of gender,

sexuality and patriarchy often

become a simplistic explanation of

all inequalities and violence in

general: structural, symbolic,

psychological, and physical. Despite

the rare sources on research on

sexuality in general, the analysed

literature shows no variety in

sexual lifes, but it is, indeed,

very rich in the evidence of

intersections between violence and

sexuality. The question that remains

open is: why? Why the past

researchers and ethnographic

evidence recorded such limited

knowledge? As posed in the

beginning, I am wondering, how much

other important 'alternative

sexualities' were dissmissed because

they really were not in existence,

or, also quite possibly, because

researchers and ethnographers simply

did not look for it. I believe that

'evolution of sexuality' does not

mean only finally starting to

research it; the struggle for

alternative practices was perhaps

always there, but for this or

another reason not taken into

account, not recorded. This is the

reason why I was trying to bring in

the importance of 'colonial gaze'

and the balkanistic attitude toward

researching sexuality. As in other

levels of seeing Balkans as 'the

Other', why would the sexuality be

an exception? If we read these

narratives, be it either before the

war, during or after, quite often

they can lead the reader to

understand the practices of

sexuality in a very exclusivistic

way, subjected to patriarchalism and

aggressive patterns of men's

behavior. When the mass rapes in

Bosnia happened, the word was

shocked. But the academia, besides

media, helped to wrap this shock to

the exlusivistic language by

'othering' the incidents to start

understanding the patriarchy, where

sexuality equals violence, unique

and peculiar to Balkans.

Women must “recolonize the space

taken from them,” says Renee

Heberle, and I would paraphrase her,

that both, men and women, have to

recolonize sexuality that was taken

from them. The resistance toward

existing rape scripts can start

happening by breaking down the

narratives that preserve images of

women as preexistent victims, women

as subjected identities. I suggest

that we aim to create the awareness

of existence of more heterogeneous,

more diverse practices of sexuality

that go beyond sexual violence and

submissive patriarchal orders. Hence

I suggest gender, sexuality, and

sexualized violence be seen not as

fixed ideologies, but created,

“lived ideology” (McCaughey in

Henderson 2013, 252), and this way

to understand the practices as fluid

subject to change and

transformation.

Bibliography

Agathangelou, Anna M. 2000.

Nationalist Narratives and

(Dis)appearing women:

State-sanctioned Sexual Violence.

Canadian Woman Studies19 (4): 12–20.

Bjelić, Dušan and Lucinda Cole.

2002. Sexualizing the Serb. In

Balkan as Metaphor: Between

Globalization and Fragmentation,

eds. DušanBjelić and ObradSavić

(297–310). London: Cambridge.

Butler, Judith. 1989. Foucault and

the Paradox of Bodily Inscriptions.

Journal of Philosophy 86 (11):

601–607.

Boehm, Christopher. 1984. Blood

Revenge: The Enactment and

Management of Conflict in Montenegro

and Other Tribal Societies.

Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press.

Bouffard, Leanna. 2010. Exploring

the Utility of Entitlement in

Understanding Sexual Aggression.

Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(5):

870–879.

Bracewell, Wendy and Alex

Drace-Francis. 2009. Balkan

Departures: Travel Writing from

Southeastern Europe. Oxford, New

York: Berghann Books.

Brownmiller, Susan. 1975. Against

Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. New

York: Simon and Schuster.

---1994. Making Female Bodies the

Battlefield. In Mass Rape: The War

Against Women in Bosnia-Herzegovina,

ed. Alexandra Siglmayer (180-182).

Lincoln and London: University of

Nebraska Press.

Buturović, Amila and Irvin Cemil

Schick. 2007. Women in the Ottoman

Balkans: Gender, Culture and

History. New York: I.B. Tauris & Co

Ltd.

Carr, Joetta and Karen M. VanDeusen.

2004. Risk Factors for Male Sexual

Aggression on College Campuses.

Journal of Family Violence 19 (5):

279–289.

Copelon, Rhonda. 1995. Gendered War

Crimes: Reconceptualizing Rape in

Time of War. In Women's Rights,

Human Rights: International Feminist

Perspectives, eds. Julie Peters and

Andrea Wolper (197–214). New York:

Routledge.

Cockburn, Cynthia. 1998. The Space

Between Us: Negotiating Gender and

National Identities in Conflict.

London: Zed Books.

--- 2007. From where we stand: War,

Women's Activism and Feminist

Analysis. London: ZED Books.

Davis, Jones. 1977. The People of

the Mediterranean: An Essay in

Comparative Social Anthropology.

London: Routledge.

Denich, Bettie. 1974. Sex and Power

in the Balkans. In Women, Culture,

and Society, eds. Michelle Rosaldo

and Louise Lamphere (243–262).

Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Djajić, Horvath Aleksandra. 2011. Of

Female Chastity and Male Arms: The

Balkan Man-Woman in the Age of the

World Picture. Journal of the

History of Sexuality 20 (2):

358–381.

Drakulić, Slavenka. 2005. They Would

Never Hurt a Fly: War Criminals on

Trial in the Hague. London: Pinguin

Publishing Group.

---2010. How We Survived Communism

and Even Laughed. London: Vintage

Durham, Marry Edith. 1928. Some

Tribal Origins, Laws and Customs of

the Balkans. London: George Allen &

Unwin.

Foucault, Michel. 1978. History of

Sexuality, Vol. 1. New York:

Pantheon Books.

Gilboa, Dahlia. 2001. Mass Rape, War

on Women. Available at:

http://www.scrippscol.edu/ (last

accessed: 7 December 2014).

Gutman, Roy. 1993. A Witness to

Genocide. New York: Macmillian

Publishing Company.

Hald, Gert M., Neil M. Malamuth and

Carlin Yuen. 2009. Pornography and

Attitudes Supporting ViolenceAgainst

Women: Revisiting the Relationshipin

Nonexperimental Studies. Aggressive

Behaviour 35: 1–7.

Heberle, Renee. 1996. Deconstructive

Strategies and the Movement against

Sexual Violence. Hypatia: Women and

Violence 11 (4): 63–76.

Helms, Elissa. 2006. Gendered

Transformation of State Power:

Masculinity, International

Intervention, and the Bosnian

Police. Nationalities Papers 34 (3):

343–61.

---2013. Innocence and

Victimhood: Gender, Nation, and

Women's Activism in Postwar

Bosnia-Herzegovina. Madison: The

University of Wisconsin Press.

Helsinki Watch. 1993. War crimes in

Bosnia and Herzegovina. New York:

Helsinki Watch, a division of Human

Rights Watch.

Henderson, Holly. 2013. Feminism,

Foucault, and Rape: A Theory and

Politics of Rape Prevention. Journal

of Gender, Law & Justice 22 (1):

225–253.

Hirschfeld, Magnus. 1941. The Sexual

History of World War. New York:

Cadillac Publishing.

Kašić, Biljana. 2005. The Spatiality

of Identities and Sexualities: Is

»Transition« a Chellenging Point at

All? In Sexuality and Gender in

Postcommunist Eastern Europe and

Russia, eds. Alexandra Štulhofer and

Theo Sandfort (95–102). New York:

Haworth Press.

Kaufman, Joyce P., and Williams P.

Kristen. 2007. Women, the State, and

War: A Comparative Perspective on

Citizenship and Nationalism.

Lanhman, MD: Lexington Books.

Kesić, Vesna. 1994. Response to

Turning rape to Pornography. Off Our

Back 24 (1): 10–11.

Kinsey, Alfred, Wardell Pomeroy and

Clyde, Martin. 1948. Sexual

Behaviour in the Human Male.

Philadelphia: Saunders.

Knežević, Anto. 1996. The Woman in

the Eyes of Patriarchal Male

Refugees: An Analysis of Some

Recently Created Bosnian Folk Songs.

Department of Philosophy, University

of Zagreb, unpublished MS.

Levin, Eve. 1989. Sex and Society in

the World of the Orthodox Slavs,

900-1700. Ithaca: Cornell University

Press.

Lewis, Linwood J. 2006. Sexuality,

Race and Ethnicity. In Sex and

Sexuality, eds. Richard D. McAnulty

and M. Michele Burnette (229–265).

Westport: Praeger Publishers.

MacKinnon, Catharine. 1994. Turning

Rape into Pornography: Postmodern

Genocide. In Mass Rape: The War

Against Women in Bosnia-Herzegovina,

ed. Alexandra Stiglmayer, Lincoln

and London: University of Nebraska

Press (73–81).

Malamuth, Neil M., Tamara Addison

and Mary Koss. 2000. Pornography and

Sexual Aggression: Are There

Reliable Effects and Can We

Understand Them? Annual Review of

Sex Research 11: 26–91.

Marić, Jovan. 1998. What Kind of

People Are We Serbs? Contribution to

the Characterology of the Serbs.

Beograd: J.Maric.

Mayer, Tamar. 2000. Gender Ironies

of Nationalism Sexing the Nation.

London: Routledge.

Moore, Monica M. 2002. Behavioral

Observation. In The Handbook for

Conducting Research on Human

Sexuality, eds. Michael Wiederman

and Bernard E. Whitley, Jr.

(113–137). Mahwah,NJ: Erlbaum.

Nagel, Joane. 2003. Race, Ethnicity,

and Sexuality: Intimate

Intersections, Forbidden Frontiers.

New York, Oxford: Oxford UP.

Olujić, Maria B. 1998. Embodiment of

Terror: Gendered Violence in

Peacetime and wartime in Croatia and

Bosnia-Herzegovina. Medical

Anthropology Quarterly 12 (1):

31–50.

Parin, Paul. 1994. Open Wounds:

Ethnopsychoanalytic Reflections on

the Wars in the Former Yugoslavia.

In Mass Rape: The War against Women

in Bosnia-Herzegovina, ed. Alexandra

Stiglmayer (35–53). Lincoln:

University of Nebraska.

Plaza, Monique. 1981. Our Damages

and Their Compensation Rape: The

will not to know of Michel Foucault.

Feminist Issues 1 (2): 25–35.

Rejali, Darius. 1996. After Feminist

Analyses of Bosnian Violence.

Available at: http://

academic.reed.edu/poli_sci/faculty/rejali/articles/bosnia96.html

(last accessed: 6 June 2014).

Salzman Todd. 1998. Rape Camps as a

Means of Ethnic Cleansing:

Religious, Cultural, and Ethical

Responses to Rape Victims in the

Former Yugoslavia. Human Rights

Quarterly 20 (2): 348–378.

Schick, Irvin Cemil. 2007. Christian

maidens, Turkish ravishers: the

sexualization of national conflict

in the late Ottoman period . In

Women in the Ottoman Balkans:

Gender, Culture and History, eds.

AmilaButurović and Irvin Cemil

Schick. New York: I.B. Tauris & Co

Ltd.

Seidman, Steven. 2003. The Social

Construction of Sexuality. New York:

W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Simič, Andrei. 1983. Machismo and

Cryptomatriarchy: Power, Affect and

Authority in the Contemporary

Yugoslav Family. Ethos 11: 66–86.

Simić, Olivera. 2012. Challenging

Bosnian Women’s Identity as Rape

Victims, as Unending Victims: The

‘Other’ Sex in Times of War. Journal

of International Women’s Studies 13

(4): 129–142.

Skjelsbaek, Inge. 2012. The

Political Psychology of War Rape.

Studies from Bosnia and Herzegovina.

London and New York: Routledge.

Snyder, Cindy S., Wesley J. Gabbard,

J. Dean May and NihadaZulcic. 2006.

On the Battleground of Women's

Bodies: Mass Rape in

Bosnia-Herzegovina. Affilia: Journal

of Women and Social Work 21 (2):

184–195.

Stein Erlich, Vera. 1966. Family in

Transition: A Study of 300 Yugoslav

Villages. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

Stiglmayer, Alexandra. 1994. Mass

Rape: The War against Women in

Bosnia-Herzegovina. Lincoln and

London: University of Nebraska

Press.

Sudman Seymour, Norman M. Bradburn

and Norbert Schwartz 1996. Thinking

about Answers: The Application of

Cognitive Processes to Survey

Methodology. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

Todorova, Maria. 2009. Imagining

Balkans. Oxford: Oxford University

Press

Tourangeau, Roger, Lance J. Rips and

Kenneth Rasinski. 2000. The

Psychology of Survey Response.

Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

United Nations. 2013. Background

Information on Sexual Violence used

as a Tool of War. Available at:

http://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/about/bgsexualviolence.shtml

(last accessed: 8 December 2014).

UNFPA. 2010. Dealing With a Legacy

of Rape and Torture in Bosnia and

Herzegovina. Available at:

http://www.unfpa.org/public/site/global/lang/en/pid/6792

(last accessed: 20 april 2012).

Wolfe, Lauren. 2012. Gloria Steinmen

on Rape in War, its Causes, and How

to Stop it: What the World can do

about Sexual Violence in Conflict.

Available at:

http://www.theatlantic.

com/international/archive/2012/02/gloria-steinem-on-rape-in-war-its-causes-and-how-to-stop-it/252470/

(last accessed: 1 May 2015).

Woodward, Susan L. 1985. The Rights

of Women: Ideology, Policy, and

Social Change in Yugoslavia. In

Women, State, and Party in Eastern

Europe, eds. Sharon L. Wolchik and

Alfred G. Meyer (234–254). Durham,

NC: Duke University Press.

Žarkov, Dubravka. 2000. Feminist

self/Ethnic self: Theory and

Politics of Women’s Activism. In War

Discourse, Women's Discourse: Essays

and Case-Studies from Yugoslavia and

Russia, ed. Svetlana Slapšak

(167–194). Ljubljana: Topos.

---2007. The Body of War: Media,

Ethnicity, and Gender in the

Break-up of Yugoslavia. Durham: Duke

University Press.

Žikić, Biljana. 2009. Dissidents

Liked Pretty Girls: Nudity,

Pornography and Quality Press in

Socialism. Medij, Istraz 16 (1):

73–95.

|