|

Wartime

sexual violence: new evidence as

hundreds of survivors come forward

By Anna Di Lellio, Mirlinda Sada and

Garentina Kraja | 22 November 2018

A wartime

survivor from Drenas. | Photo:

Valerie Plesch.

Following a trail

of fresh evidence from wartime

sexual violence survivors in Kosovo,

researchers connect the dots and

reveal the true pattern of sexual

violence as a weapon of war and

ethnic cleansing across the country.

The first time the

crime of wartime sexual violence was

given the label of “tool of war” was

during the conflict in Bosnia and

Herzegovina. Though targeting all

ethnic groups, Serbian security

forces used sexual violence

systematically against Bosnian women

as part of their strategy of ethnic

cleansing.

Nearly 20 years

after the Kosovo war of 1998-1999,

survivors come forward and identify

the date, the place and the

circumstances surrounding instances

of sexual assault. We can prove that

sexual violence was used as a tool

of war in Kosovo as well. It was

never just a practice, a “bad thing”

tolerated by commanders as the war

raged on.

At the

International Criminal Tribunal for

Yugoslavia in The Hague, ICTY,

sexual violence in Bosnia and

Herzegovina featured prominently in

the conviction of senior military

figures. The trials of Serbian

military and security leaders

indicted for war crimes and crimes

against humanity in Kosovo had

different outcomes in regard to the

count of sexual assault: General

Nebojsa Pavkovic was convicted in

the first instance, but Nikola

Sainovic, Sreten Lukic, and

Vlastimir Djordjevic were found not

guilty, because only a handful of

witnesses had testified.

Only on appeal, in

2014, were all of them convicted on

charges of wartime sexual violence.

The Court ruled, reversing its

previous trial judgements, that

these leaders knew, but did nothing

to stop, the widespread sexual

violence that was occurring at the

same time as destruction of

property, mass expulsions and mass

killing of Albanian civilians. In

that context, sexual violence

amounted to persecution of a group

and a crime against humanity.

We can now add new

and more damning evidence to the

Court’s conclusion.

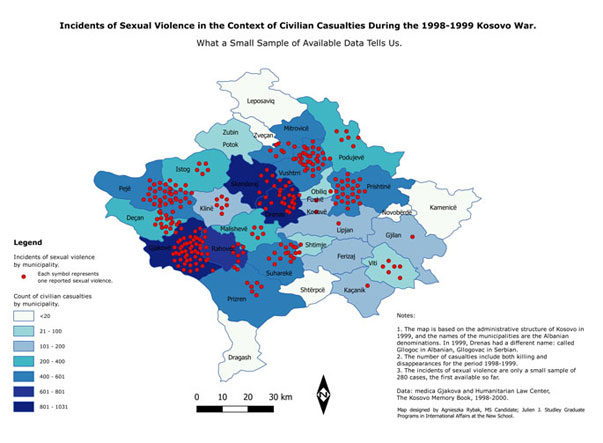

Data collected

from 280 survivors of wartime sexual

violence perpetrated by the Serbian

Army, the police, and the unofficial

groups of perpetrators they

commanded, prove that there was a

pattern, a logic and an intent to

the use of sexual assault as a

weapon deployed systematically and

strategically along with mass

murder, the burning and the

pillaging of property, targeting

Albanian civilians.

This evidence

completely disproves the Serbian

leaders’ line of defense: that they

did not know their forces were

raping Albanian women, that rape was

never a strategy, and that if it

happened, it was just a sporadic,

opportunistic act.

The cases we

analyzed are just a small number in

comparison with the total count of

survivors, but together with the

complete data on civilian casualties

compiled by the Kosovo Humanitarian

Law Center, there is a large enough

sample to map the strategy of terror

and destruction planned by the

Milosevic regime.

The map shows

without any ambiguity that killing,

disappearances and sexual violence

in Kosovo during 1998 and 1999 were

overlapping throughout the war

against Albanian civilians. It

confirms what OSCE and Human Rights

Watch investigators had concluded as

early as 1999: sexual violence was

“a weapon of ethnic cleansing” in

Kosovo, like in Bosnia.

We looked at the

data and asked the question: what

was happening in those places at the

same time that sexual violence was

happening? Looking into the stories

of just a fraction of the survivors

interviewed, we can affirm what the

court was only ever able to imply.

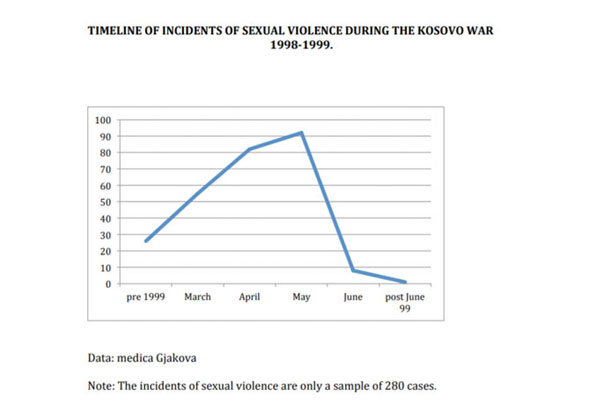

The timeline: mapping sexual

violence in the Kosovo war

We noticed a

sizable number of incidents from

Beleg and Carrabreg, just south of

Decan, between March 25 and March

28, 1999. That is exactly when

Serbian troops clamped down first on

Upper and Lower Carrabreg, then on

Beleg.

All the people,

villagers coming from a larger

surrounding area who had not found

refuge in the mountains, were told

they had five minutes to leave their

homes; everyone was robbed of cash

and everything of value they

possessed; all the houses were

burned; men were stripped naked,

publicly humiliated and randomly

shot; and several women, displaced

from the larger surrounding area,

were put in a barn and raped by

multiple perpetrators.

Finally, they were

all loaded on tractors and driven to

the Albanian border. The final tally

of civilian casualties is 38, and we

now know that there are many more

survivors of sexual violence than

the two witnesses who summoned the

courage to testify in The Hague: we

counted a total of 15 in our sample

alone.

A cluster of rapes

happened in the larger area

surrounding Shtutice and Verbec

,Drenas, on April 28 and 29, 1999.

Then on the night of April 29, NATO

bombed the Feronikel factory, a

legitimate and legal military

target, since it had been used as a

base and a detention facility where

torture was practiced. The bombing

elicited an even more brutal attack

on Albanian civilians, and more

rapes. Early on April 30 Serbian

troops seized Shtutice and Verbec

and killed respectively 44 and 80

civilians. All the houses were

burned, and many more civilians were

taken prisoners and held overnight

at the mosque in Cirez.

The next day,

during the transport to prison, 102

were taken off the trucks and

executed at the Shavarina mines in

Citakove e Vjeter. Before and after

the killing, many women were

tortured: we know of 17 of them.

Incidents cluster

in significant numbers in Studime,

the prison of Smrekonice, and

Vushtrri, around May 2, 1999. On

that day, columns of displaced

people pushed by Serbian forces out

of their homes in the surrounding

area and converging on Studime, to

the east of Vushtrri, were harassed

and robbed by police and army

despite the display of a white flag.

The women were

separated from the men and a number

of them were held in a school, many

were raped, 22 in our sample, as the

men were being killed, 106 of them

in one day.

The rest of the

displaced, taken to the prison of

Smerkovice, endured from two to

three weeks of illegal detention

during which they were tortured,

denied food, and held in inhumanely

cramped quarters.

On May 22 they

began to be released daily in groups

and were marched to the border with

Albania. Some were pulled out of the

convoy and publicly sexually

assaulted at the Ramiz Sadiku

cemetery, as two survivors

testified. From June 22 through June

8, about 3,000 men who had been

detained at Smerkovice crossed the

border into Kukes. Many had their

hands broken from the beating and

knew nothing of their wives and

mothers from whom they had been

separated in Studime.

Finally, what

explains the multiple rapes in

Dragaqine, a remote village seven

kilometer north east of Suhareke?

Fighting had

stopped there by end of March, and

displaced people had gathered there,

but Serbian troops returned on April

21, 1999, killing a dozen of men and

raping several women. We counted 8

in our sample.

We looked at the

data and heard the stories of

survivor. They are all very clear

about what happened. Victims were of

all ages: at the two extremes, a

nine-year-old and a

seventy-year-old.

The majority of

these survivors were not only raped,

but also scarred with cigarette

burns and knife cuts. They were the

victims of multiple aggressors,

cursed and insulted for their ethnic

origin. They were left traumatized,

as the living embodiment of the

attempt to destroy an entire people.

Their entire experience is a

textbook definition of rape as a

weapon in a strategy of ethnic

cleansing.

Anna Di

Lellio is a Professor of

International Relations at New York

University and The New School, NY.

Garentina

Kraja is an independent researcher

working from Kosovo.

Mirlinda

Sada is the executive director of

NGO Medica Gjakova.

Feature

photo: Valerie Plesch.

|