|

Introduction

The creation of

Yugoslavia was not motivated by

economic or even social development,

but its establishment was rather to

serve the usual reasons of the state

- above all security, but also

equity. The latter, understood as

the fulfillment of national – in the

sense of ethnic – rights and

objectives, was also the basis for

its legitimacy. However, no durable

agreement was ever reached on the

constitutional framework of its

national and Yugoslav legitimacy. In

the pursuit of an equitable solution

to its national issues, the country

was in a state of perpetual crisis

of legitimacy. This unfulfilled

nationalism blocked its

democratization and resulted in the

adoption of misguided decisions,

among others also in the domain of

economic policy.

Both the economic

and political history of Yugoslavia

consists of a series of ill-advised

constitutional decisions and then

intermittent attempts to implement

necessary reforms so as to rectify

these decisions. These decisions

would regularly go on to prove

themselves as untenable since they

were guided by the same, mainly

ethnic or national motives. Some

form of dictatorship was always seen

as justified, above all from the

perspective of security. And then

one form or other of territorial

devolution was used to seek out

equity for national-territorial and

economic interests.

At the same time,

the external circumstances were not

favorable. The country needed (i) a

liberal-democratic constitution in

an era of rising nationalism; (ii)

the development of a

private-ownership-based economy open

for exchange with the world in a

time of growing protectionism and

totalitarianism and (iii) the rule

of law in revolutionary times.

Favorable conditions for

liberalization and democratization

occurred only on the eve of the

country’s dissolution.

During the last

couple of decades after the

break-up, seven ex-Yugoslav states

co-exist within a system of regional

cooperation that suffers from the

same shortcomings as the former

common state. Thus the current

situation seems as temporary and

unnatural as any of the Yugoslav

structures from the inception of the

common state to its disappearance.

Even though the

common state was conceived as a

project in modernization, both

national and social, the overall

consequence of the Yugoslav

political and economic explorations,

which regularly brought about

short-lived and misguided solutions,

was backwardness, and not only

economic at that. This failure

should not be taken as proof against

the project itself since neither

before nor after the existence of

Yugoslavia have political

instability and a general lagging

behind been removed. But history is

not suitable for counterfactual

evaluation, except when speculating

about the future. In real time,

let’s say towards the end of the

1980s, the project of a democratic

Yugoslavia was not inferior to its

nationalist alternatives measured by

what could be expected from those

alternatives. But nationalisms

prevailed, and this is now history,

which needs to be explained. That

the fall was so steep represents a

challenge to that explanation. But

that is a matter of political choice

and not historical inevitability.

This text will

deal with a historical overview of

Yugoslavia’s economic development

and economic policy, with attention

focusing on the period after 1948.

First, I’ll set out the theoretical

framework then I’ll show the most

significant institutional and

developmental characteristics, then

outline above all the fiscal

dilemmas of the joint state and

finally, sketch out the economic

development after the dissolution,

that is, during the last few

decades. Separately, in short

asides, I’ll focus on the financial

crisis, the collapse of economic

reforms from the 1960s, the

stagnation of the 1980s, the unequal

development of the new states, and

the creation of a common market in

2006.

Politics between Nationalism and

Liberalism

Political history

is not completely positivistic since

it is based at least on the tacit

assumption that there are certain

durable regularities, if not

full-scale historical laws. These

regularities exist for two reasons.

One is the perpetual problems faced

by those who make political

decisions. On the one hand, there is

the need to secure a certain level

of public goods, above all security,

and on the other, there are changing

circumstances, which require

adjustability in carrying out

political objectives. The other

reason is that constitutional or

other government solutions constrain

the available set of means which can

be used to resolve durable political

problems in changing external and

internal circumstances. This

primarily concerns the

constitutional framework that is the

basis for legitimacy, regardless of

the fact how much support one

government or another, one holder of

office or another actually has.

On the other hand,

economic history is at least

partially autonomous in relation to

political decisions and, in fact, is

part of the changing circumstances

that have to be taken into account

in decision-making since both

objectives and especially available

means are subject to change. This is

due to both the development of

technology and changes in the

significance and character of

external economic relations. Foreign

trade and public finances are

undoubtedly of great significance

for small countries and small

economies. Yugoslavia was certainly

a small country, at least from the

economic perspective. Even more so

are the post-Yugoslav countries that

emerged after the break-up of the

common state.

Bearing in mind

the political circumstances and the

economic development of the 20th

century, Yugoslavia represented a

political solution from the

standpoint of the basic political

problem, the problem of security as

a public good. The problem it

perpetually faced, however, lay in

the discrepancy between the

nationalist conception of politics

and the economic need for liberal

relations both internally and

externally. Consequently, the state

could not secure the desired level

of equity and justice and was

confronted with social discontent

regarding the level and distribution

of wealth.

On the one hand,

the country was supposed to

reconcile the nationalist conception

of equity with the liberal demands

of economic development. The latter,

in turn, spurred social discontent.

The country fell apart when

nationalism became the political

expression of social

dissatisfaction. At the same time,

the liberal-democratic alternative

was rejected. After the break-up,

the sluggish and indecisive

democratization and liberalization

were the cause of a relatively

unsatisfactory political and

economic development, partly also

due to misguided economic policy.

Therefore, the

discord between nationalist

objectives and liberal means is,

simply put, the reason behind the

perpetual instability of the

Yugoslav state and the practically

constant adoption of misguided, or

at best, short-sighted political

solutions.

A General Overview

of Development

The data on

Yugoslavia’s development is not

unknown and therefore it is

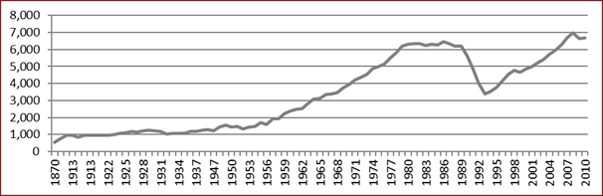

unnecessary to go into detail. Image

1 shows the GDP per capita in steady

dollars. From 1921 to the outbreak

of World War II, the country was not

characterized by any exceptional

economic progress. In that, however,

it was no different from the

majority of neighboring countries,

whether it be, for example, Greece,

Hungary or Bulgaria. Partly this was

the consequence of demographic

growth, but since we are talking

about several decades, it is clear

that on the whole the economy was

stagnant and that it is not possible

to talk about any significant

progress in relation to economic

development on Yugoslav territory in

the time before the establishment of

the common state.

Image 1:

Yugoslavia, GDP per capita, steady dollar

Source: Maddison database

Development in the

years after World War II, if we put

aside the years of the Soviet

blockade, is characterized by

significant economic growth and

development, if the latter is

expressed, again, by the per capita

GDP. While in the first twenty years

or so the GDP per capita increased

just under 40 percent, in the period

from 1952 to 1979 it increased just

under 5 times. As in both cases it

was a matter of rebuilding the

country after great war devastation,

there is no doubt that Yugoslavia

after World War II achieved an

incomparably better economic

development than it did after World

War I. Of course, one has to bear in

mind that economic development the

world over was much faster, and not

only compared to the development in

the period between the two great

wars, but was in fact much faster

than in any previous period in

history – at least to the degree

that such comparisons are at all

possible.

This can also be seen by comparison

with neighboring countries, all of

which had successful economic growth

in the period after World War II,

before the end of 1970 and in the

decade that followed. Irrespective

of statistical problems, due to

which comparisons are not always

fruitful, there is no doubt that,

for example, Greece, Hungary and

Bulgaria, not to mention the more

developed countries of Western

Europe, also had accelerated

economic growth and development.

In fact, the 1980s are the key here.

Namely, in that period all socialist

countries, including Yugoslavia,

underwent economic stagnation and

decelerated growth. This can also be

seen in Table 1. In the period from

1979 to 1989 there is actually zero

growth of per capita income. A

similar situation prevailed in

neighbouring Bulgaria and Hungary,

but, for example, not in Greece. And

if to this group we add Austria, it

becomes completely clear that this

stagnation was not a consequence of

European, much less world, economic

trends. In order to understand the

break-up of Yugoslavia, this is

certainly the most important

political and economic period.

This is followed by the 1990s,

which, up to 1993-1994, brought a

reduction of economic activity by

about roughly a half, even though it

was about a third smaller than in

the years 1979, 1989 and 1999.

Recovery begins again after 2000 –

and for all ex-Yugoslav countries

together it is such that on the

whole the levels from 1979 and 1989

are reached again. Nevertheless, one

has to bear in mind the demographic

changes, which are now negative, for

a part of the population was lost

due to the wars, due to a negative

birthrate, and due to emigration.

All the same, when the GDP per

capita is in question, for about

thirty years, for all ex-Yugoslav

states taken together, it barely

marked an increase. In other words,

the country or countries had

stagnated for practically three

decades.

Finally, economic development ground

to a halt or was significantly

slowed down – if not completely

negative – after 2008, as a

consequence of the global financial

crisis. Some ex-Yugoslav states

fared better than others – which in

itself neccessitates an explanation.

In this context, the role of the

liberalization of trade both with

the European Union, as well as

regionally by the establishment of a

regional free trade zone known as

CEFTA (Central European Free Trade

Agreement), was of great

significance. The European Union had

opened its market to those

ex-Yugoslav countries that had not

joined the EU like Slovenia in 2001.

CEFTA, in turn, had inherited

bilateral free trade agreements when

it was established in 2006. In any

case, one cannot stress enough the

importance of foreign trade for

these very small ex-Yugoslav

economies.

In the century between the

establishment of Yugoslavia and the

present, development was either slow

or unsustainable. In the entire

period, however, there was no

political stability either in

Yugoslavia, or between the newly

independent states, and not even

within them internally. And this

irrespective of the great, in

reality revolutionary, changes and

independently of the different

constitutional reforms and political

changes, including changes in

economic policy. The common country,

as well as the independent states,

did not aspire towards

democratization, while

liberalization measures were often

confronted by suspicion about who

was better and who worse off.

Non-democratic solutions and the

non-liberal economic policy

temporarily contributed to

stabilization, but in the long run

they signified the abandonment of a

more durable political community.

The consequence of this discord

between nationalist interests and

liberal means of economic

development is the long-term lagging

behind of the Yugoslav countries.

There is no simple explanation for

this stagnation. Geographically,

Yugoslavia is in the immediate

vicinity of the developed world, so

this backwardness, if one can call

it such, could not be explained by

geographic isolation from the

advanced part of the world.

Moreover, at least at the time of

stagnation during the 1980s,

external circumstances in fact

favored the political changes that

were necessary in order for the

country to join the developed part

of the world. So that the lack of

development and lagging behind,

especially during the last forty

years, can only be explained by the

decisions made by the Yugoslav

authorities, the authorities of the

Yugoslav republics and autonomous

provinces, and the authorities of

the newly independent states – and

not in the last resort by the

citizens.

Regional Differences

Bearing in mind the permanent

instability of the country, it is

not unimportant to see whether

dissatisfaction was based on the

enduring bias of the political and

economic system towards one or

another region. Again, the data for

development after World War II is

better and more easily compared than

the data for the period between the

two great wars. Also, it can be

analyzed more or less in detail.

Still, a rough picture of

comparative development can be

gained on the basis of differences

in per capita income.

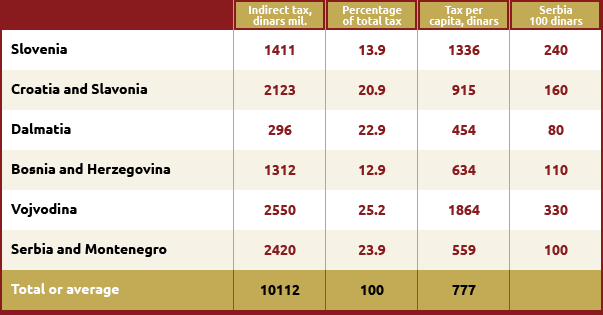

Table 1

Per capita national product in 1910, US dollar (1970 value)

Source:

Palairet, The Balkan Economy. CUP,

1997. pp. 233.

For the period before the

establishment of Yugoslavia there

are varying assessments of

differences in development and one

of these is given in Table 1. The

data for Slovenia and Macedonia is

missing, but the differences in

development could not have been too

great because even the differences

in relation to Austria and the Czech

Republic are not as great as they

would be later. In any case,

regional differences, which were to

dominate the (economic and

political) debates in both

Yugoslavias, do not appear to be

such as to represent an

insurmountable obstacle to creating

a common state.

For the period between the two wars

the quality of the data leaves

something to be desired. This was

due, among other things, to frequent

changes in internal regions.

Probably the most influential was

the claim by Rudolf Bićanić that

more developed regions, which had

been a part of Austria-Hungary

before the unification (of

Yugoslavia), were paying higher

agrarian land tax rates than Serbia,

Montenegro and Dalmatia. Table 2

provides a cumulative review for the

period before the Great Economic

Depression.

Table 2

Land tax,

1919-1928

Source:

Bicanic

Differences in tax burdens wouldbe

the subject of political disputes

throughout the entire history of

Yugoslavia as the common country. An

additional subject of disagreement

was the expenditure of public funds

in which it was usually claimed that

greater investments are being poured

into less developed areas – that is,

into Serbia between the two wars –

and fewer into the more developed.

As agriculture was the dominant

economic activity in the first

Yugoslavia, data on different

agrarian land tax burdens is

undoubtedly significant. It is

important to note that with time the

budget was less dependent on

indirect taxes – which included

agrarian land tax – and that these

made up about 50 percent of the

budget immediately after the

establishment of the common state,

falling to about a third of overall

tax revenue before World War II,

while the share in the budget from

immediate taxes and revenues from

state enterprises went up. Before

the war the overall sum of the

latter was just below from what it

was from indirect taxes.

The main objection during that

period, however, was that the tax

burden of the more developed areas

had increased in the transition from

Austria-Hungary to the Yugoslav

state. This undoubtedly continued to

be a hot topic later as well when

tax burdens in Yugoslavia were

compared to the ones in the newly

independent states. It must be said

that it is not unexpected that a new

state should invest more in its

underdeveloped areas because it is

reasonable to expect that regional

differences should decrease after

state unification. After all, this

is the key economic rationale in

establishing any common state.

Therefore, this was to become the

second most important topic of

debate – could Yugoslavia secure the

kind of economic growth that would

lead to an evening-out of the level

of economic growth in all of its

regions, could it lead to a

convergence in the per capita income

levels?

The data is not reliable in the case

of the first Yugoslavia, but since

the overall growth was modest, it

would not be realistic to expect

that a particularly significant

increase of regional differences had

taken place. Besides, if and to the

degree that it happened, the effects

of negative international economic

trends would in all likelihood have

to be greater than any domestic

redistribution of funds. This, of

course, doesn’t change the substance

of the problem of equity, both as

regards the less developed as well

as the more developed regions

because all expectations are that,

in the long run, the state would

secure a convergence of the levels

of per capita income between the

regions. To put it another way, it

would be reasonable to expect that

less developed areas have faster

economic growth than more developed

areas in order to even out the

levels of the standard of living

throughout the country.

It is not very likely that this

occurred in the first Yugoslavia,

but the interesting question here is

whether the second Yugoslavia

secured faster economic growth for

the less developed republics and

provinces? This is the subject of

enormous amounts of research, but

the rough and very general answer is

not particularly contentious. In

other words, there was no obvious

convergence in economic development

between the particular regions. This

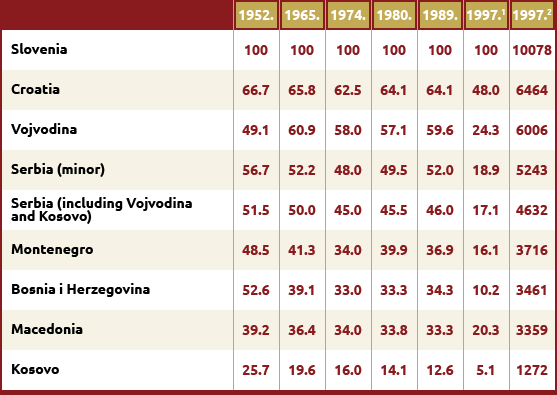

can be seen from Table 3.

Table 3:

Gross Domestic Product per capita

(Slovenia = 100, unless otherwise

indicated)

Notes:

1) Data for 1997. refer to gross

material product per capita for all

Yugoslav republics (including

Kosovo) and gross domestic product

for other countries. – 2) The actual

GDP per capita (in USD according to

the exchange rate) for Slovenia and

the hypothetically achievable level

of GDP per capita (in USD according

to the exchange rate) for other

republics, assuming that the

differences in the region (measured

according to the GDP per capita) are

the same as in 1989.

Source:

The Vienna Institute for

International Economic Studies

for 1997 and 1999 and the OECD for

other years.

Slovenia’s GDP per capita equals

100. As can be seen from the table,

the Croatian per capita GDP was

about two thirds of Slovenia’s, the

Serbian about half, the autonomous

province of Vojvodina’s about 60

percent, while the other republics

and provinces trailed behind with

roughly a third of Slovenia’s per

capita GDP. Kosovo lagged behind

mainly because of its high birth

rate – but its overall (economic)

growth rate was even a little higher

than in other parts of the country.

The less developed regions underwent

slower progress in the first period

after 1952, which, at least in part,

was due to isolation from external

markets after the introduction of

the so-called Iron Curtain. It is

also important to note that there

were no further negative

consequences as regards their

development, especially if one takes

into account the demographic

changes, after the changes in the

economic system in the mid-1960s.

Generally speaking, one could not

say that Yugoslavia had managed to

secure convergent development for

different parts of the country. In

fact, particularly after the

systemic changes in the mid-1960s,

it seems that regional development,

in better and worse times, was

fairly balanced. Regional

differences were not small – with

the exception of Kosovo, up to a

ratio of 1 to 3 – but such

differences are not unheard of in

many complex countries. However, the

fact that over time they did not

change significantly, and

particularly that they were not

significantly reduced, points to

systemic deficiencies and also

challenges the economic rationale of

the political, especially the

nationalist, disputes - the latter

particularly if one takes into

account the difference in employment

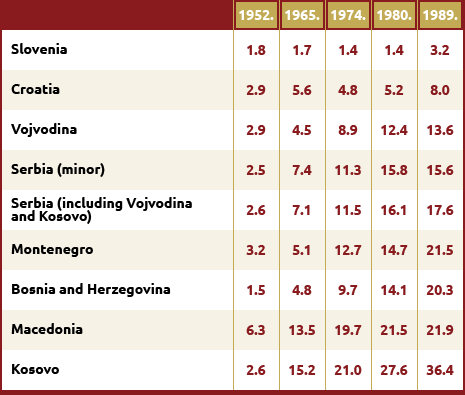

and unemployment. Table 4 gives the

rates of unemployment from 1952 to

just before the break-up.

Table 4:

Unemployment

rate in %

Source:

OECD.

It is clear from the above that the

less developed areas were, partly

due to higher demographic activity,

much worse off in terms of the labor

market than the developed areas. In

truth, the high unemployment rate

that was especially prominent in the

1980s has remained a structural

economic characteristic for the

majority of the new independent

states to this day. The causes are

surely not the same, at least not

entirely. It is important to point

to the durability of low employment

and high unemployment even in

Croatia after it became independent,

but it is particularly important to

do so in the other regions and

states. Slovenia is an exception

here – and this is of notable

significance in explaining the

dissolution of the common country –

because Slovenia was a leader among

the secessionists, at least from

around 1988. This casts doubt on the

explanation for the country’s

break-up, which states that it is to

be found in Yugoslavia’s economic

failure and the failure of its

economic system, which was biased in

favor of the underdeveloped regions

and against the more developed ones.

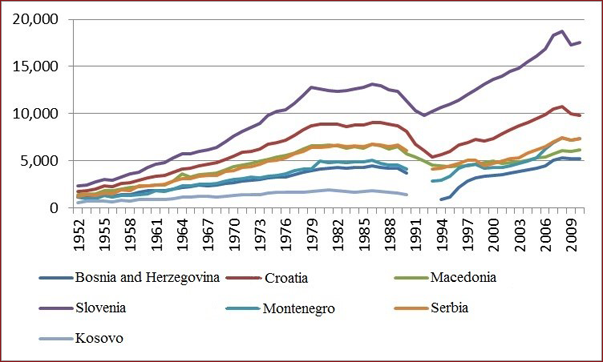

Image 2:

National

income per capita

Source:

Maddison database

After the break-up of the country,

there was a great increase in

regional differences, that is, in

differences pertaining to the

economic activity of the states that

emerged from Yugoslavia. Table 3

also gives the state of affairs at

the end of the 1990s, when these

differences, due to the consequences

of the wars, were the greatest. In

the meantime there came about a

relative convergence, which can

partly be discerned from Image 2,

but nevertheless today's differences

are greater than in any period of

Yugoslav history and if one is to

believe the data from admittedly not

very reliable sources, regional

differences were also smaller before

the establishment of the common

state in 1918.

All in all, Yugoslavia was not a

country with convergent economic

development, but neither was it

particularly biased, negatively or

positively, towards the less

developed areas, at least if we are

to judge by the growth of the per

capita income. The overall

development, expressed as per capita

income, can be seen pretty clearly

in Image 2. The differences between

the republics did not change

significantly (Kosovo is the

exception due to its demographic

growth), and then increased in

relation to Slovenia and later in

relation to Croatia as well, while

the others converged, especially

with Serbia.

Concerning employment and social

development, the less developed

areas were on the whole lagging

behind. A more detailed analysis

would certainly show that

development in different segments

and particular fields was not

unequivocal, especially where

education and the development of

industrial production are concerned,

but this would not be of crucial

importance in explaining stability

and the sustainability of the

economy and the state.

Reform and Deadlock

Most attention has probably been

focused on studying the

self-management system and the

economic reforms of the mid-1960s.

The motivation was as much political

as it was economic. Finances from

abroad also played an important

role, as did bilateral aid and

multilateral credits and finally

access to the foreign financial

market. The political limitation was

maintenance of the one-party

monopoly of power.

Generally speaking, socialist

reforms followed the strategy –

first economic, and then political

reform - in other words, first

liberalization of the market, and

then democratization. The program of

the League of Communists of

Yugoslavia from 1958 contains a

clear ranking of alternative

systems. A multi-party democracy was

more acceptable than the Soviet

system if socialist self-management

and non-party pluralism proved to be

unsustainable, in the sense that

they are neither economically nor

politically more progressive than

alternative systems. One could,

therefore, say that democratization

was seen as the political exit

strategy if it turned out that there

was no other way to maintain

political stability and economic

development.

One problem was the nationalization

of investments. A key systemic

difference between capitalism and

socialism was – and as a matter of

fact, still is – who initiates

investment decisions? The

nationalization of assets was the

precondition for the state to

monopolize investment decisions.

Investments were financed from the

profits of companies that were in

state ownership on the basis of a

central plan. This is the very

essence of the Soviet system which

was established by Stalin’s

collectivization and nationalization

of the 1930s. In the beginning,

self-management was seen as a

transfer of the management role to

the economic collectives, that is,

companies. The reforms of the

sixties brought about a change in

ownership relations, state property

became social property and thus the

central, state-owned investment fund

was abolished. With it went the

system of central planning, too. The

power to decide on investments was

conferred, at least nominally, on

the companies which themselves –

albeit in the name of society – were

owned by the workers employed in

them. Finally, and probably most

importantly, normal trade and

financial relations with the world

were established, mediated by

commercial banks. This, in turn,

necessitated conducting the usual

monetary and fiscal policy.

The final motivation, however, was

that the next reform and future

economic and political adaptations

would lead to privatization and

democratization. And truly, with

certain constitutional solutions and

changes to the electoral system from

the beginning of the sixties, it

seemed as if things were starting to

move in that direction. To this one

should add the opening up of borders

and an increase in international

cooperation. All these systemic

changes had a temporary character

and the next changes were to involve

privatization and democratization.

At least, this is how things looked

in the mid-sixties.

The reforms turned out to be a

political failure. Their

continuation was abandoned, while

political changes took a completely

different, if not unexpected,

course. Privatization was stopped by

the student protests of 1968, while

democratization was halted by

nationalist movements that

threatened to bring about the

break-up of the country, also

occurring in 1968. The result was

that the majority of economic

changes were kept, although later

certain elements of the economic

system were modified so as to

harmonize with the political

changes. The latter, on the other

hand, went mainly in the direction

of strengthening the republics and

provinces at the expense of the

federation. Of key importance here

were the changes to the banking

system and the system of public

finances. In a sense,

nationalization (by the republics

and provinces – trans.) of assets

and taxpayers came about.

The research, both

foreign and domestic, most

frequently focused on the wrong

issues. Foreign economic research,

which was extensive, focused with

special intensity on the performance

of self-management companies and

their drawbacks that were to be

expected if one started out from the

assumptions of economic theory. On

the other hand, domestic studies

were devoted to the country’s

downgrading mostly from the legal or

constitutional aspects, as well as

to the shortcomings of a

decentralized socialist system in

which it was not possible to control

wages or investments from a center,

since the federation lacked above

all the fiscal, but also political

instruments necessary.

Of crucial importance, however, was

the relinquishing of further

democratization, which came about in

order to preserve stability – and

was achieved by a return to

authoritarianism and by a

redistribution of national

competencies. A debate similar to

the one conducted in the first

Yugoslavia, above all after the

territorial reorganization of 1939,

was renewed. This turnabout also

determined the political disputes

and their solutions which ultimately

led to the break-up of the country.

How did a system created to stop

economic reforms function? During

the 1970s, monetary policy was

mainly used to make sure that the

economy did business with a negative

real interest rate. This was a key

macroeconomic fact. As the federal

government had very limited powers

in the domain of fiscal policy,

monetary policy was the most

important instrument of overall

economic policy. Details are not of

paramount importance; it is

sufficient to point out that

interest rates were lower than the

rate of inflation in conditions of

what was practically a fixed rate of

exchange. As a consequence, this led

to an increase of investment and

spending, financed by foreign loans

and a growth in imports. As money

was cheap globally in the seventies,

this kind of economic policy was not

at odds with what was going on, not

only in the developed countries of

the world, but in some socialist

countries as well. Yugoslavia

probably fared better than most

because its foreign debt was to a

large degree funneled into

investments, while in other

socialist countries, for example the

Soviet Union, it was directed

towards spending (on wheat imports,

for example). Nevertheless, a great

disparity in the trade balance

developed, while foreign debt

accumulated. All the way up to the

economic crash of the eighties.

The economic system created in the

mid-sixties was supposed to increase

the efficiency of investments and

spur competitiveness on foreign

markets. The sum of reform measures

undertaken then were not that

different from those undertaken by

countries at the time of abandoning

socialism at the end of the eighties

and beginning of the nineties. The

regime of the foreign exchange rate

was balanced out, central banks were

empowered to deal with inflation,

while the fiscal system was meant to

secure the sustainability of public

finances. Finally, commercial banks

were established that took deposits

in hard currency and gradually

became capable of taking out foreign

loans and financing the investments

of domestic companies. Direct

foreign investments were not

possible, and neither were private

domestic investments - shortcomings

that were intended to be eliminated

at a later date. The system thus

established was capable of recycling

foreign assets, as well as of

monetary subsidies to the economy –

which in fact it did do once further

reforms were relinquished. So the

system that was established to

increase the efficiency of the

economy was ultimately used to

sustain self-management companies,

national budgets and buying

stability by increasing spending.

The seventies were the time when

this system produced favorable

results. Much research sees this

period – and the short period of

Ante Markovic’s government in 1990 –

as the golden age of Yugoslavia. The

dinar was strong, imported goods

were accessible, investments raised

the economy’s capacities, and in the

infrastructure was partially renewed

or enlarged. Remittances from abroad

also made a certain contribution

since in the sixties a great number

of workers had emigrated to Germany

and other countries that enjoyed

faster growth than there was

available work force. Thus a

macroeconomic system was established

that in certain elements persisted

mainly in Serbia up until the crisis

of 2008-2009.

Foreign Trade

Judging by the data of the Yugoslav

National Bank, the balance of trade

in the first Yugoslavia was on the

whole equalized. The economy was

pretty closed, measured by the ratio

of imports to exports and domestic

production. It was a matter of some

ten percent, that is, around twenty

if overall foreign exchange was

taken into account. In part this was

a consequence of the economic trends

immediately after World War I, when

inflation was a problem throughout

Europe, and then came the Great

Depression when foreign trade was

reduced everywhere. In later years,

the state attempted to utilize

protection measures, which curtailed

imports, but also exports since

there would occasionally be a ban on

exporting agricultural goods, which

was the most important export

commodity.

In the second Yugoslavia, financing

from abroad played a significant

role and thus imports were on the

whole greater than exports. Still,

the trade deficit began to be

significant only after the economic

reforms of the sixties, and became

particularly so after the political

stabilization at the beginning of

the seventies. Apart from the

policies of the exchange rate

(relatively stable) and of prices

(accelerated inflation), a

significant role was played by

increasing remittances from abroad.

Also, in the second half of the

seventies especially, loans taken

abroad also played a significant

role. By the end of the seventies,

exports covered imports by about 50

percent. The balance of services was

positive due to transit revenues, as

well as growing tourism, so that, if

remittances from workers abroad are

taken into account, the current

account of the balance of payments

showed a lesser deficit. This

characteristic will endure in the

majority of the newly- independent

states, at least until the crisis of

2008-2009.

Table 5

Trade flows

in the Socialist Federal Republic of

Yugoslavia1

Placement

on the local market, in % GDP

Placement

in other regions, in % GDP

Export,

in % GDP

Note: -

1) Includes end products and

intermediates.

Source:

OECD.

Table 5 contains data on domestic

and foreign trade. As can be seen,

the domestic market was certainly

much more important than the foreign

market, a characteristic which will

again persist even after the

break-up of the country, albeit not

in Slovenia, while things begin to

change under the influence of the

crisis of the eighties. The role of

this crisis is also visible in Table

5.

Table 6

Trade in

Southeast Europe (1980-1985)

Notes:

1) West Germany. – 2) SEE-1

(Southeast Europe - 1) Includes

Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and

Yugoslavia. – 3) SEE-2 (Southeast

Europe - 2) Includes SEE-1 with

Greece and Turkey.

Source:

The Vienna Institute

forIinternational Economic Studies

Right after the outbreak of the

crisis at the beginning of the

eighties, exports show a significant

growth in relation to GDP. Moreover,

this whole decade will show a much

more equalized trade balance than

the previous decade. The overall

picture becomes even better if we

add the export of services, which

became very significant with the

development of tourism. Generally

speaking, if overall foreign

exchange is taken into account,

Yugoslavia in the period after the

economic reforms (of the 1960s) was

trade-wise a significantly more open

country than the majority of the

successor states after the break-up,

but before the crisis of 2008-2009.

Table 7

Trade in

Southeast Europe (1990.)

Notes:

1) Including West and East Germany.

– 2) SEE-1 (Southeast Europe - 1)

Includes Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania,

and Yugoslavia. – 3) SEE-2

(Southeast Europe - 2) Includes

SEE-1 with Greece and Turkey.

Source:

The Vienna Institute for

International Economic Studies

It is also interesting to note the

change in trade partners during the

crisis of the 1980s. Tables 6 and 7

contain some comparative data. The

second half of the eighties sees a

significant increase of exports to

Germany and Italy, which will go on

to become the most significant trade

partners of the newly-emerged

independent states as well. Imports

from these two countries were

already significant earlier. In any

case, Yugoslavia had an increasingly

open economy in the period after the

economic reforms of the sixties.

The Lost Decade

The eighties were of key

significance not only for

Yugoslavia, but for the European

socialist world as a whole. If we

look at Images 1 and 2 it is clear

that this was a decade in which the

economy stagnated. From Tables 3 and

4 it can be seen that certain

republics fared better than others,

especially where employment was

concerned. But in terms of economic

growth there is practically little

difference between the regions. The

case was similar with other

socialist countries, even though the

reasons were different. In some,

like Yugoslavia, the problem was

high foreign debt, while in others

it was the drop in prices of oil and

other raw materials.

Yugoslavia practically went bankrupt

in 1981-1982 because it was unable

to pay back its foreign debt. The

reason for this was that monetary

policy had changed in the United

States and there was a sudden jump

in interest rates. Given that at the

time the foreign trade deficit of

Yugoslavia was really huge, the

further financing of imports through

foreign loans was not sustainable

and thus it was necessary to

rebalance imports and exports.

Furthermore, it was necessary to

secure the refinancing of already

existing loans at much higher, and

from the position of the country’s

trade capabilities, unsustainable

interest rates. A reduction of the

foreign trade deficit required a

significant correction to the dinar

exchange rate, while financing of

debt called for finding new sources

of revenue. The country, however,

could not adapt quickly enough and

actually never managed to fully

adapt all the way up to its very

break- up. Why?

The reason was of a systemic nature.

Here it is necessary to bear in mind

three key characteristics.

The first was the dispute over the

dinar exchange rate. Devaluation

would redistribute expenditures

among the republics. The issue of

hard currency earnings from tourism

was particularly sensitive. The

export sector, especially tourism,

would certainly gain from

devaluation, while sellers on the

domestic market would be worse off.

There was no mechanism of

compensation, mainly because the

fiscal system had changed

significantly in the meantime so

that the federal budget no longer

had the necessary means to

compensate those who fared worse

from revenue achieved by taxing

those who fared better. The central

bank used the hard currency rate of

exchange and selective lines of

credit to compensate, but this only

increased the disputes because the

terms were inequitable in a matter

that should have been equitable. In

fact, in this way the central bank

incurred obligations that could then

easily be turned into losses and

thus into fiscal expenditure for the

republics and provinces.

The second characteristic was the

expectation that credit would be

worth less when it became payable

because a negative interest rate

would be ascribed to it. In

conditions of loss of value of the

exchange rate, it would have been

necessary for inflation not to

compensate corrections to the

nominal exchange rate. This would

have, however, required a

significant change in the behavior

of companies, which, in turn, did

not show a willingness to sacrifice

implicit subvention through

accelerated inflation. And so the

entire decade was marked by losses

in the exchange rate and a parallel

acceleration of inflation. The

correction of the trade deficit was

more a consequence of the inability

to finance it and less a result of

exchange rate and monetary policies.

The third characteristic is probably

the most important. As a consequence

of social and national resistance to

economic reforms, one was precluded

from selling property as a means to

finance foreign debt. At the

beginning of the crisis in

1981-1982, foreign debt made up less

than a third of the overall Yugoslav

product. Interest rate obligations

were not small, but they in no way

exceeded several percentage points

of the domestic product. It would

have been relatively easy to turn

the debt into foreign investment if

companies had been allowed to issue

shares so as to secure the necessary

financing. This was not feasible

because of the ownership system

which precluded the sale of

property, especially to foreigners,

but also to private individuals in

general, and because it could also

lead to the spilling-over of

obligations and profits across the

borders of republics and provinces,

which was politically very hard to

swallow. It was not until 1988 that

agreement was reached with the

International Monetary Fund about

solidarity in sharing responsibility

for the foreign debt of the country.

These obstacles to a relatively

quick solution to the problem of

foreign debt made it very difficult

to start up economic production in

improved macroeconomic conditions,

which ultimately resulted in the

economy stagnating for a whole

decade with the constant

acceleration of inflation and growth

of the unemployment rate. Only at

the end of 1989 the government of

Ante Marković embarked on changing

these systemic characteristics,

which in the short term led to

improved economic trends in 1990,

but also to a renewed economic

crisis at the end of that year and

finally to the break-up of the

country in 1991.

During that entire decade, the

advocates of liberal economic

solutions and democratic political

legitimacy could not garner public

support for the necessary changes

while, at the same time, the

influence of the nationalists grew

until they finally prevailed in

Serbia, after which the break-up of

the country was inevitable. The more

developed republics repeatedly

highlighted the inequity of the

fiscal system, which was the alleged

cause of the overspill of their

assets to less developed regions,

while in Serbia the interest in new

territorial delimitation along

ethnic lines prevailed. While fiscal

problems were solvable, territorial

delineation along ethnic lines

naturally signified the end of the

common state.

Breakdown and Setback

Practically from the very inception

of the common state, the

distribution of gains and

expenditures between its constituent

parts was the key topic of debate

and dispute. The constitutional

framework was never accepted by

certain national (ethnic)

communities and in certain places

local control of the territory was

disputed. In the economic domain,

the fiscal system was deemed

inequitable by practically all

sides. In the end, the country broke

apart over the dispute of who was

paying how much into the common

coffer. This, of course, was just

the rationalization. However, this

dispute was to be expected given

that the diminishment of fiscal

powers by the federal government had

been a key demand from 1968 up to

the break- up itself. There was thus

first a fiscal devolution, which was

thoroughgoing and practically

complete, and then the Fund for the

Underdeveloped, which was

practically the only remaining

fiscal instrument for the

reallocation of assets, became the

focus of disputes, and then finally

even the central bank, which

intervened with selective credits

thus causing different regional

consequences, became a contentious

issue.

What was the specific problem with

the Central Bank and the banking

system as a whole? In the period of

adaptation to the crisis of foreign

debt during the eighties, the

financial picture changed in such a

way that the developed republics had

a trade surplus in exchange with the

less developed republics and the

province of Kosovo. In other words,

the country had divided itself into

creditor and debtor republics. The

financial significance of Slovenia

grew markedly. In part this was a

consequence of the Fund for the

Underdeveloped, even though it was

precisely the more developed

republics, above all Croatia and

Slovenia, which sought its

abolishment. However, to the degree

that money really moved from, let’s

say, Slovenia to Macedonia, goods

followed the money, too. So the

republics that had paid more money

into the Fund for the Underdeveloped

and then left it were also the

republics who sold more of their

goods to the less developed

republics and the province of

Kosovo. This was simply the domestic

balance of payments: that domestic

trade was financed by credits from

the more developed republics,

turning them into creditor

republics, while the lesser

developed regions became the

debtors. Because of this financial

asymmetry, measures that would in

one way or another assist the

financial recovery of the debtors

were not acceptable to the creditor

republics. But if the balance of

power at the level of the federal

government had changed, that could

have become feasible.

In this context, the rise of

nationalism in Serbia was of special

concern. The motives of the Serbian

nationalists were neither economic

nor predominantly financial (apart

from personal interest, of course).

Instead, they sought a change in the

balance of power at the federal

level with the objective of revising

the existing constitution and making

possible territorial corrections.

And truly, the Serbian nationalist

movement was a combination of

anti-liberal social demands from

1968 and nationalist territorial

demands above all towards the

provinces (Vojvodina and Kosovo –

trans.), but implicitly also towards

other regions (in other republics)

populated by Serbs (so-called

‘Serbian lands’ – trans.). These

political objectives brought about

the break-up of the country. But the

country never functioned well

economically either, and the

necessary reforms were not in

harmony with any of the Yugoslav

actors’ nationalist interests.

Costs of the Break Up

The nineties were economically bad

for all the states that emerged out

of Yugoslavia except for Slovenia.

There was a disruption of trade

ties, except for those within the

rump Yugoslavia (Serbia and

Montenegro – trans.), and between

Bosnia-Herzegovina and neighboring

Serbia and Croatia, but the scope of

that exchange was significantly less

than before the break-up and the

wars. Table 3 shows the difference

of the real per capita income in

relation to the income that would

have been achieved had long-term

relations with the Slovenian economy

been maintained. So that during the

nineties all other emerging Yugoslav

countries started lagging

significantly behind Slovenia, but

also behind other European

countries. From Image 2 it can be

seen that in practically all the

newly-emerged Yugoslav states the

level of the per capita income at

the beginning of the second decade

of the 21st century was on a par

with the level achieved during the

seventies or eighties (given that

the eighties were marked by

stagnation). In other words., the

countries in question had lost about

three decades of development. If we

take into account that the bigger

countries – Croatia, Serbia,

Bosnia-Herzegovina – did not achieve

visible growth in the period from

2008 until today, then we can even

talk about four decades of

stagnation. Only Slovenia had

positive growth, even though by

certain indicators, today it too is

further away from the European

developed countries than it was at

the end of the seventies or the end

of the eighties.

All in all, it is difficult to talk

about the economic benefits of

leaving Yugoslavia. Furthermore, if

one is to compare tax burdens,

especially bearing in mind the gains

of such tax expenditures, and

putting aside defense spending,

which in the second Yugoslavia was

considerable and today is much

reduced, it is difficult to claim

that the newly-emerged states are

less of a burden to the taxpayers

and the economy. It neither runs

counter to logic nor simple fact

that smaller states pose a greater

burden on taxpayers (with the

exception of micro-states, but only

Montenegro qualifies as such),

simply for reasons of the economy of

scope.

Finally, in terms of democratization

and liberalization, the

newly-independent states, with the

exception of Slovenia, are more

restricted than Yugoslavia, or at

least this has only started to

change very recently.

Democratization is incomplete and a

few of the newly-emerged states are

going through a constitutional

limbo. Slovenia and Croatia have

become European Union members, a

fact that has a stabilizing effect

on the economy and on political

relations, but the rest of the

former Yugoslavia has not achieved a

more durable stabilization of the

democratic system of

decision-making.

Regional Cooperation

After the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina

and particularly after the war in

Kosovo, the international community,

especially the United States and the

European Union, formulated a policy

of regional cooperation with the

idea that increased economic

cooperation would bring about

political stabilization and

normalization. The European Union

has invested substantial effort in

mobilizing interest in regional

cooperation principally among the

former Yugoslav states. Probably the

most important such regional project

is the regional free trade zone

known as CEFTA. It was established

in 2006 after existing bilateral

agreements on free trade developed

into a regional agreement. The

European Union additionally

supported this project by first

removing customs barriers on imports

from the Yugoslav countries, and

then concluding with them Agreements

on Stabilization and Association

which would ultimately lead to

European Union membership. With

CEFTA and free trade with the

European Union, liberalization

finally prevailed in the

newly-emerged Yugoslav states.

What is the possible contribution of

liberalization to economic

development? This is particularly

interesting because the crisis that

took hold of the Yugoslav states

from 2008 up to the present has a

lot in common with the crisis from

the beginning of the eighties. In

the same way, the period that

preceded the crisis has much in

common with the period from the

seventies. Thus these two distinct

crisis periods and their

consequences are comparable.

Development after 2000, which

represents a kind of new beginning

for the entire region since both

(Croatian strongman) Franjo Tudjman

and (Serbian strongman) Slobodan

Milošević exited the political

stage, has the same characteristics

of uneven progress as the period of

the seventies. Trade deficits

increase, foreign debt becomes

greater, and unemployment has not

been reduced to an acceptable

level.. The last is noteworthy among

other things because many

explanations for the growth of

unemployment in Yugoslavia after the

economic reforms (of the sixties)

can be understood differently today.

Back then explanations saw the

growth of unemployment as caused by

institutional factors, especially by

the system of self-management.

Namely, employees as owners have an

interest in increasing investments

and not increasing the number of

employed because that way they

increase their own income, which

apart from their salary also

partakes in the company profits..

This should explain the growth of

capital in relation to labor and the

limited mobility of the labor force.

Nevertheless, when one looks at

development in the majority of

European post-socialist or

transition countries, one notices

that the tendency for economic

growth to be based on growth in

productivity and not growth in

employment, is present everywhere.

This makes sense if the development

in question is financed by foreign

assets, as was to a large degree the

case in Yugoslavia after the

economic reforms because investments

will be turned into the most

productive technology, due to which,

again, employment will grow at a

slower rate, particularly if it is a

question of those employed in the

state sector being pre-qualified for

work in the new industries or the

services sector. So that in

transition economies, and such at

the outset was the Yugoslav economy

after economic reforms, productivity

takes precedence over employment.

This to a large degree also occurred

in the emerging Yugoslav states in

the first decade of the 21st

century. Growth was mainly based on

productivity, while employment even

showed a tendency to shrink.

Therefore the problem lay not in

unemployment, but rather in the

economic sectors in which

investments were directed. During

the seventies, Yugoslavia invested

in industry, but not an

insignificant part of the foreign

debt went into spending.

Additionally, efficiency was a

problem due to negative interest

rate subsidies. By contrast, most

emerging Yugoslav states, except for

Croatia and Montenegro, made use of

the post-2000 period of low interest

rates mainly to invest in non-export

services. As a result, by and large

foreign debt was directed into the

production of non-exchangeable goods

and into spending. Ultimately, all

the former Yugoslav countries faced

the financial crisis of 2008 with

high foreign debt. Just as at

beginning of the eighties, the

refinancing of these debts was made

difficult, not so much by the higher

cost of loans, but by the need for

foreign creditors to put their own

finances into order. And so the

entire region found itself in a

similar situation to the one from

the 1980s, with the difference that

there was now little leftover

property, the sale of which would

help cover the debts. Thus it was

necessary to correct the exchange

rate where it was overvalued, or cut

spending, by reducing employment if

there was no other way, leading to a

leveling-out of the current balance

of payments with greater exports and

reduced imports. This is a process

that has been underway for almost a

decade in the new Yugoslav states,

which, time-wise, is similar to the

eighties.

Here it is important only to see

what the role of a more liberal

trade framework is in relation to

the one from the 1980s. The

existence of a regional free trade

zone was certainly helpful, for it

preserved the level of trade

inherited from the period prior to

2008. However, access to the market

of the European Union had

significantly more impact. In the

period from 2008 to 2016, all the

new Yugoslav countries increased

their exports from 30 to 60 percent,

with imports stagnating at a level

close to that of 2008. The advantage

of liberalization today in relation

to resistance against it during the

eighties certainly influenced

adaptability to the crisis. Even

though the key problems - foreign

trade deficits and foreign debt -

are the same.

However, it is worth pointing out

that, irrespective of the above, the

European Union is increasingly

unpopular, that nationalism is on

the rise, and that regional

cooperation has occurred in spite

of, and not as a consequence of, the

policies of the new Yugoslav states.

Conclusion

Yugoslavia did not succeed in

achieving liberalization and

democratization, but it was not an

obstacle to them either since the

newly-emerging states after its

dissolution have not displayed a

durable affinity for liberal

measures or sustainable democracy,

nor, for that matter, for regional

cooperation either. However,

circumstances have changed and so

far nationalist and authoritarian

forces have not prevailed as they

did when they dissolved the joint

state. The economic cost of

non-liberal and nationalist politics

is permanent backwardness due to

their unsustainability in conditions

of modern development.

Literature

Bicanic, R, Ekonomska podloga

hrvatskog pitanja (The Economic

Basis of the Croatian National

Issue). Zagreb, 2004 (first edition

1933).

Gligorov, V, Why Do Countries Break

Up? The Case of Yugoslavia. Uppsala,

1994.

Gligorov, V, „Elusive Development in

the Balkans: Research Findings“,

wiiw Policy Notes and Reports 2016

(wiiw - Wiener Institut für

Internationale

Wirtschaftsvergleiche; Vienna

Institute for International Economic

Studies).

Lampe, J. R, Yugoslavia as History.

Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Palairet, M, Balkan Economies c.

1980-1914: Evolution without

Development. Cambridge University

Press, 1997.

|