|

Introduction

The fact that the

architecture of modernism represents

an important part of the cultural

heritage of the Kingdom of

Yugoslavia and, in particular,

socialist Yugoslavia, seems to be a

peculiar truism. It is also known

that the emergence and rapid

development of the architecture of

modernism were linked to two

groundbreaking years in the history

of both states – 1929, when the

Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and

Slovenes changed its name, structure

and ideological direction, after the

imposition of the so-called 6

January Dictatorship and collapse of

parliamentarism, and 1948, when the

Cominform Resolution was adopted and

the relations with the Soviet Union

were temporarily broken off. During

the fourth decade of the 20th

century, just like during the sixth,

seventh and eighth decade, something

that is usually considered as

“architectural modernism” or “modern

architecture” became the dominant

architectural idiom in Yugoslavia.

In each synchronic cross-section it

was both the part of the repertoire

of the official state representation

and the inviolable poetical credo of

the generations of Yugoslav

architects. However, the intrinsic

link between the Yugoslav

architecture of modernism and its

raison d'être in its own historical

context or, in other words, the

relation between poetics and

politics remained in the shadow of

great historiographic narratives

about the local variations of global

modernism and the autonomy of

architecture as part of the modern

project.

If we understand

the term “modernism” as an

emancipatory shift towards the

transformation of society and

progressivist movement towards its

imaginary contours on the “horizon

of the expected”, then the role of

the architecture of modernism in the

history of the first and second

Yugoslavia must inevitably be

redirected. Architecture must be

relocated from the sphere of

autonomous theory and practice, that

is, the part of culture that is

usually understood as the sphere

enclosed by specificity and

peculiarity, and defined not only by

poetical boundaries, but also by

ideological and political ones. In

fact, we understand architecture not

as an autonomous and self-sufficient

reality, but as the constituent part

of an imaginative world of ideology

within which different

“architectural phenomena” (ranging

from individual elements, buildings,

through formal and stylistic

characteristics, to the broader

concept of architecture as an

epistemological project and

discipline) represent semantical

structures which are crucial for the

creation of an idea of collective

belonging and identity.

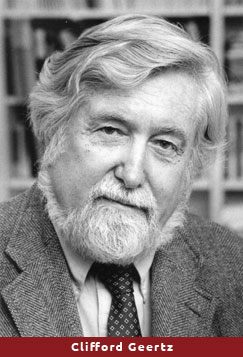

At the same time,

one must bear in mind that modernism

is a specific ideological construct

of historiography and criticism or,

in other words, the projection of

the basically different and

seemingly universal value systems

onto cultural artifacts and

processes, whereby “culture” must be

understood in the anthropological

sense of the word or, for example,

from the usual perspective if

interpretive theories of culture,

like the one advanced in the works

by Clifford Geertz. Thus, we will

also view the architecture of

modernism as part of a symbolic

universe in which it objectivized

and formally shaped social reality,

while at the same time shaping

itself relative to it and vice

versa. In this connection, one must

always bear in mind the difference

between the interconnected notions

of “culture” and “society” based on

Talcott Parsons and Edward Shils’s

classical model, defining culture

(and architecture as its integral

part) as a semantic system or

symbolic world, while society is

determined by a network of social

relations whose meaning is given

just by cultural forms. Thus,

architecture also cannot be

understood outside the social

context from which it originates as

part of the modern project, but the

ways in which its relationship, as

an integral part of culture and

society, is perceived and

established, are different. On the

one side, according to the most

vital interpretive tradition of

modern art — from Clement Greenberg,

through Giulio Carlo Argan, to

Filiberto Menna – the art of

modernism is understood as a

fundamental part of the

progressivist paradigm of societal

development, that is, a specific

pedagogical instrument and

methodological model for society; in

addition, it forms part of the

modern project as the process of

building critical answers to the

questions posed by social reality.

On the other side, however,

according to contemporary scientific

interpretations – which view culture

as an ideological system that shapes

the values defining society and

building collective identities – the

architecture of modernism emerges as

one of the ideological orders or

symbolic practices. In any case, the

link between modernist architecture

and social context is crucial for

understanding or interpreting its

cultural specificities and social

roles, the task that imposes itself

upon every historian dealing with

this historical phenomenon. At the same time,

one must bear in mind that modernism

is a specific ideological construct

of historiography and criticism or,

in other words, the projection of

the basically different and

seemingly universal value systems

onto cultural artifacts and

processes, whereby “culture” must be

understood in the anthropological

sense of the word or, for example,

from the usual perspective if

interpretive theories of culture,

like the one advanced in the works

by Clifford Geertz. Thus, we will

also view the architecture of

modernism as part of a symbolic

universe in which it objectivized

and formally shaped social reality,

while at the same time shaping

itself relative to it and vice

versa. In this connection, one must

always bear in mind the difference

between the interconnected notions

of “culture” and “society” based on

Talcott Parsons and Edward Shils’s

classical model, defining culture

(and architecture as its integral

part) as a semantic system or

symbolic world, while society is

determined by a network of social

relations whose meaning is given

just by cultural forms. Thus,

architecture also cannot be

understood outside the social

context from which it originates as

part of the modern project, but the

ways in which its relationship, as

an integral part of culture and

society, is perceived and

established, are different. On the

one side, according to the most

vital interpretive tradition of

modern art — from Clement Greenberg,

through Giulio Carlo Argan, to

Filiberto Menna – the art of

modernism is understood as a

fundamental part of the

progressivist paradigm of societal

development, that is, a specific

pedagogical instrument and

methodological model for society; in

addition, it forms part of the

modern project as the process of

building critical answers to the

questions posed by social reality.

On the other side, however,

according to contemporary scientific

interpretations – which view culture

as an ideological system that shapes

the values defining society and

building collective identities – the

architecture of modernism emerges as

one of the ideological orders or

symbolic practices. In any case, the

link between modernist architecture

and social context is crucial for

understanding or interpreting its

cultural specificities and social

roles, the task that imposes itself

upon every historian dealing with

this historical phenomenon.

The mentioned contemplations form a

conceptual framework within which

the overview of the architecture of

modernism in the first and second

Yugoslavia will be made. This

overview does not intend to be

all-embracing and present a

comprehensive picture, or point to

all manifestations and achievements

of this phenomenon. Focus will be

laid on the consideration of the

cultural specificities of the

architecture of modernism in the

Yugoslav context and the related

ideological roles. This is also a

modest contribution towards getting

over the fear of historicism that

prevails in the significant part of

architectural historiography in

Serbia, although it alone is derived

from the culture of the modern

project. Should architectural

modernism be separated from what it

designated in its context, that is,

from its own semiotic sphere, we

would face the challenge of the

random or nonrandom creation of a

peculiar forgery. Just as history is

not an autonomous field of the

interpretation of the past, but

represents an effort toward its

careful conceptualization, the

history of architectural modernism

in Yugoslavia cannot be reduced to

the issues of the formal, stylistic

or social aspects of architecture.

Instead, it must explore its

meanings from a broader perspective,

involving the creation of the value

system and identity model.

Therefore, the common view that the

architecture of modernism advocated

a distinctive value system based on

progressivism, evolutionism and

other universal premises, and

generated a number of poetic

strategies, formal patterns and

stylistic characteristics,

constructing architecture as an

autonomous cultural object, must be

put in parentheses.

Understandably,

our approach has its limitations

and, like any other interpretation,

is the result of a conscious

compromise between subordination to

the supratextual plane of theory and

the historization of “modern

architecture”, which is constantly

hindered by the discourse of its

autonomy. Such an approach to the

architecture of modernism can help

us enter the conceptual (and

political) world in which those who

found themselves within the Yugoslav

borders in the period 1929-1980

lived. We will view architectural

modernism as a symbolic framework

for something that the political

regimes in the first and second

Yugoslavia pitted against social

reality — or, in other words, as the

ideological patterns deriving their

power and effectiveness from real

political life and not from the

protected fields of architectural

theory and history.

***

Toward the end of

the third decade of the 20th

century, the modernist breakthrough

into Yugoslavia’s architectural

culture was violent and tempestuous.

As early as the mid-1929, “modern

architecture” became omnipresent in

public space. Indeed, in almost

every interpretation of the

phenomenon of modernism it was

emphasized that the abrupt emergence

of modern architecture in a

conservative environment, like that

of the Yugoslav capital, was made

possible by a series of

circumstances, whereby a decisive

role was played by the royal

dictatorship imposed by King

Aleksandar I Karadjordjević. It was

emphasized that the “6 January

regime” contributed to the

legalization of a break with the

past, and that in the early 1930s

new architecture, as an opposite to

“old historical styles”, was widely

accepted in the whole country.

Indeed, modernism could respond

symbolically to the political

demands for national unification and

depict the Yugoslav nation, culture

and state without “tribal blindness”

or “spiritual chaos” — everything

that caused the sharp change of the

political course in the early 1929

which, after the tragic events in

the Yugoslav parliament in the

previous year’s summer, occurred

during the time interval between the

imposition of the royal dictatorship

and promulgation of the so-called

octroyed constitution in early

September 1931.

Understandably,

the simultaneity of an abrupt

ideological change and the emergence

of architectural modernism was not

the fruit of chance. The allegedly

ahistorical character and universal

language of “modern architecture”

functioned as the cultural

confirmation of the new course and

had a significant role and great

power, primarily because they

represented a positive projection of

the demands for national

unification, ethnic unity, break

with the past and erasure of

“tribal”, political and cultural

traditions. In contrast to other

stylistic and formal configurations

on the architectural scene — and, in

particular, different “national” and

regional idioms — modernism was not

burdened by the existing national or

ethnic conceptions, so that it

became the most convenient means for

the representation of an ideal

environment for the new Yugoslav man

and idealized image of the new

Yugoslav culture.

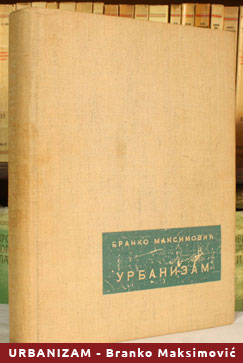

When in the

mid-1930s Belgrade’s architect

Branko Maksimović clearly pointed

out that “modern architecture

completely rejects all those narrow

national borders and thus

contributes to some extent to

rapprochement among peoples”, that

was only one of the cultural values

determined by Belgrade’s architects

and political elites as being the

basic characteristic of modern

architecture. The new idiom was

playing an increasingly greater role

in the rhetoric of the then

reactualized integral Yugoslavism

and was also gaining ground in

public space. Truly, Belgrade’s

public instantly accepted the

language of architectural modernism

due to a number of other reasons. In

a broader context, architectural

modernism also represented a

peculiar simulation of progress and,

like historical-style architecture,

civilizational foundation.

Nevertheless, its key role lied in

the fact that it helped cultivate

Yugoslav national authenticity

through the politically promoted

thesis that modern architecture

would erase cultural and ethnic

boundaries, and that it was based on

“authentic” vernacular architecture.

In fact, “international” modernism

experienced its “nationalization”,

while modern architecture became

part of the construction of

primordial Yugoslav identity that

could be interpreted and used in

diverse political registers. When in the

mid-1930s Belgrade’s architect

Branko Maksimović clearly pointed

out that “modern architecture

completely rejects all those narrow

national borders and thus

contributes to some extent to

rapprochement among peoples”, that

was only one of the cultural values

determined by Belgrade’s architects

and political elites as being the

basic characteristic of modern

architecture. The new idiom was

playing an increasingly greater role

in the rhetoric of the then

reactualized integral Yugoslavism

and was also gaining ground in

public space. Truly, Belgrade’s

public instantly accepted the

language of architectural modernism

due to a number of other reasons. In

a broader context, architectural

modernism also represented a

peculiar simulation of progress and,

like historical-style architecture,

civilizational foundation.

Nevertheless, its key role lied in

the fact that it helped cultivate

Yugoslav national authenticity

through the politically promoted

thesis that modern architecture

would erase cultural and ethnic

boundaries, and that it was based on

“authentic” vernacular architecture.

In fact, “international” modernism

experienced its “nationalization”,

while modern architecture became

part of the construction of

primordial Yugoslav identity that

could be interpreted and used in

diverse political registers.

It only seems

paradoxical that architectural

modernism could be mobilized for the

construction of different national

and cultural identities in different

contexts. In Yugoslavia during the

1930s the same shaping idiom could

be interpreted in the key of

Yugoslav, Serbian or Croatian

national identity. At the same time,

it could also connote leftist

ideology – just like in the case of

the Soviet Union, “Red Vienna”,

public architecture of the socialist

municipalities in Germany during the

1930s, or Jewish cultural identity —

not only in the interpretive

tradition of National Socialism, but

also in the light of the then usual

identification of modern

architecture and Jewishness, in

particular. In the context of this

semiotic fluidity of modernism, it

is especially ironic that Croatian

nationalism, one of the centrifugal

ideologies relative to Yugoslavism

during the 1930s, fixed the

architecture of modernism before the

mirror which would reflect

everything conceived by its

protagonists, rallied primarily

around the group called “Zemlja”

(Earth). The practice of Croatian

nationalists to interpret

architectural modernism as the

formula of an unadulterated demotic,

Croatian national identity was

congtruent with the actions towards

the Yugoslavization of modern

architecture, which were carried out

in Belgrade.

At the same time,

architectural modernism was the

instrumental formula of the new

Yugoslav regime, placing the state

and its nation under the aegis of

the Western civilization, anchored

in the idea of progress. In the

positivist-evolutionist concept of

culture, modernism was identified as

a more perfect cultural formation

relative to the past, which

corresponded to the ideological

requirements of the dictatorship of

King Aleksandar I Karadjordjević. In

a similar way it also corresponded

to the requirements of the

secularization and cultural

levelling of Turkish national

identity at the time of the Kemal

Ataturk regime, which was at its

zenith. In general, one must bear in

mind that, during the late 1920s and

1930s, linking modernist

architecture to new political

ideologies or social, economic and

political reforms was a universal

phenomenon – extending from the

Soviet Union and Fascist regime in

Italy, as well as the revolutionary

and totalitarian regimes in Central

Europe (Hungary, Czechoslovakia,

Romania and Poland), to Kemalism in

Turkey, or Zionism at the time Tel

Aviv was built. In all mentioned

cases, the discourse of

architectural modernism legalized

these new regimes as “progressive”

and “reform-oriented”. Just from

that perspective it is necessary to

perceive the role of architectural

modernism in the Kingdom of

Yugoslavia, which is evidenced by

the fact that the crucial

architectural representations backed

by the regime were based on the

recognizable modernist vocabulary —

ranging from official national

pavilions at the world expositions

(Barcelona, 1929; Milan, 1931;

Paris, 1937) to, for example, the

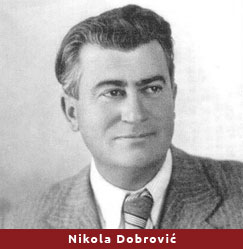

architectural competition for the

construction of Terazije Terrace in

Belgrade at which the seemingly

quite “modernist” design of Nikola

Dobrović won the first prize (1929). architectural modernism legalized

these new regimes as “progressive”

and “reform-oriented”. Just from

that perspective it is necessary to

perceive the role of architectural

modernism in the Kingdom of

Yugoslavia, which is evidenced by

the fact that the crucial

architectural representations backed

by the regime were based on the

recognizable modernist vocabulary —

ranging from official national

pavilions at the world expositions

(Barcelona, 1929; Milan, 1931;

Paris, 1937) to, for example, the

architectural competition for the

construction of Terazije Terrace in

Belgrade at which the seemingly

quite “modernist” design of Nikola

Dobrović won the first prize (1929).

In Yugoslavia’s

specific political context at the

end of the third and at the

beginning of the fourth decade of

the 20th century, modernist

architecture advocated a broad

spectrum of cultural values with a

distinctly political dimension. Just

thanks to this broad spectrum,

architecture became one of the most

important forms of representing

Yugoslavism. The accompanying danger

of the national, social or general

political disintegration of Yugoslav

society, echoes of the

intensification of the global

economic crisis and series of

foreign political factors,

contributed that modernism became an

inexhaustible treasury for the

presentation of the desirable

attributes of the Yugoslav nation,

and the system of its cultural

values and cultural policy, so that

it won over almost the entire public

space in the Yugoslav capital within

a short time. It is important to

note that already in the early

1930s, thanks to architectural

modernism, something being

increasingly viewed as

“international modernism” was

adopted as being consistent with the

idea of Yugoslav national culture,

which was shaping the original

national identity that transcended

the ethnic boundaries of Serbdom,

Croatdom and Slovenedom – for two

crucial reasons. The first and less

important reason was the

international character of modern

architecture and its conscious

neglect of everything local or

ahistorical. The second reason

seemingly distorted the ahistorical

dimension of modernism by pointing

to deep structural relations between

the “modern building method” and,

understandably, ideologically

acceptable vernacular architectural

heritage. Namely, in the discourse

of integral Yugoslavism vernacular

architecture was already designated

as the representation of the

original primordial tradition that

allegedly faithfully reflected the

idea of the unadulterated Yugoslav

spirit. During the fourth decade,

pro-Yugoslav architects,

intellectuals and political elites

advanced the theses about the

conceptual, structural and ethical

correspondence between vernacular

and contemporary architecture, thus

interpreting architectural modernism

as the contemporary reincarnation of

the “Yugoslav” national tradition.

At the time when the shift away from

ethnic particularisms represented a

tour de force of the overall

cultural policy, the construction of

“authentic” identity was a much more

complex venture than the

interpretation of modernism as

simply building “in a contemporary

way”. One of the crucial roles in

this ambitious venture was assigned

to the discourses of modernist

architecture. The allegedly

original, national and – according

to the established ideological

analogy – genuine Yugoslav

architecture emerged, as it was

held, in the “spirit of the national

genius” much before the beginning of

the separate tribal histories of

Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. However,

the new architecture of modernism

was nothing else but the reinvention

of the existing national tradition.

It used new materials and forms, but

its inner essence remained the same.

What was common to modern and

national architecture from the

perspective of the culture of

Yugoslav nationalism included their

common ideals, primarily a direct

relationship between man, nature and

material culture. Thus, the

architecture of modernism became a

direct and authentic link with the

primordial Yugoslav past. Thus, a

direct relation was established

between the authentic Yugoslav

nation — which was believed to exist

from time immemorial but, due to

historical circumstances, was split

into three tribes — and the

contemporary national community of

Yugoslavs. At the same time, by

linking the principles and elements

of modern architecture to local,

profane architecture the idea was

developed that, thanks to its

authentic spirit, Yugoslav national

culture already belonged to the

contemporary Western civilization.

***

Just this shift

towards the West was one of the

important aspects in the cultural

and political construction of

Yugoslavia’s “specific road” to

communism when, after the invention

of the Yugoslav “socialist

democracy” and self-management

system in the early 1960s, the

architecture of modernism reassumed

a crucial role in the legitimization

of the “new situation”. Like in the

post-1929 period, when integral

Yugoslavism needed a material,

tangible form, the specificity of

Yugoslav socialism was legitimized

by new, modernist architecture. In

both cases, the resolute shift away

from historicism and the pastiche of

historical and “national” styles,

meant symbolic distancing from one

ideological direction, one value

system and one identity concept, and

transition to quite a different

ideological identity domain.

As is well known,

the specificities of the second

Yugoslavia were reflected in its

position relative to the Cold War

division of the world, authenticity

and originality of Yugoslav

socialism, and the policy of the

proclaimed specific road as an

autonomous heading toward a

classless communist society.

Contrary to what was usually

understood as the rigid bureaucratic

centralism and etatism of the Soviet

Union and Eastern Bloc countries, on

the one side, and Western political

liberalism, on the other side, the

Yugoslav elites tried to find,

establish and preserve the complex

ideological construction of

“Yugoslavia at the crossroads”.

Paving Yugoslavia’s specific road to

communism was marked by its role

relative to the global political,

social and economic order, the role

that was instrumentalized by the

policy of non-alignment and active

peaceful co-existence on the

international plane, and the

principles of all-embracing

decentralization, workers’

self-management and social ownership

concept at home. The characteristics

of Yugoslavia’s specificity pointed

to the country’s mediatory role and

something presented by its

intellectual elites as an

avant-garde in the development of

the consciousness of humanity in its

heading towards the new, liberated

man and humanized society. By

bridging the gap between the

socialist system and democracy,

Yugoslavia’s socialist democracy

also had to bridge a triple gap

between the ever-changing reality of

everyday life, fixed image of the

surmounted past and proclaimed

vision of the future. Such a

transitional situation, as the

crucial feature of the ideology that

legitimized Yugoslavia’s political

system and process of its continuous

transformation, was basically

associated with the belief in the

inevitable withering away of the

state — the fundamental principle

derived from the interpretation of

original Marxism — that is, the

transformation of the state into the

post-state. During the period

between 1952, when the principle of

self-management was introduced, and

the death of Josip Broz Tito, which

symbolically marked a new phase in

the history of socialist Yugoslavia,

transformation, reforms and

instability established themselves

as the structure of long duration,

which characterized all constituent

elements of the federal state.

In this context,

architecture played a fundamental

role. Its place in building the

ideology of Yugoslavia’s socialist

democracy rested above all upon the

projection of the personal freedom

of each individual, as the basis for

the emancipation of the entire

society and its segments, as well as

upon the idea about the autonomy of

architecture. In the Yugoslav

context, the architecture of

modernism acquired a peculiar

teleological position, so that it

virtually and literally presented

the picture of the promised future

toward which the entire society was

heading. As both a symbolic and

actual construction of the

ideological system, architecture

advocated the idea of progress,

freedom, transition and continuous

evolution, thus legitimizing a broad

modernization process. This implied

the interpretation of the new system

of management and “deetatization” as

the transition of the state

functions to free citizens and,

according to Aleksandar Ranković,

the strengthening of their

confidence in the “value of their

personal freedom and human rights,

and the role of individual citizen

in the management of social life”.

At the pragmatic level of

architectural culture, this policy

was based on the Western model of

identifying modernism in arts and

architecture with liberalism, and

shifting away from communism (as

contrasted to the usual associations

of modernism and leftism before the

Second World War), which was

developed during the Cold War

period.

The peculiar

teleological position of modernist

architecture in socialist Yugoslavia

can best be illustrated by numerous

architectural and urban planning

competitions and general urban

plans, which not only outlined the

desired “future situation”, but also

played a strong educational role in

Yugoslavia’s architectural and

political culture. Although most of

these plans were never realized,

their place in public space

significantly determined and

confirmed the contents on which the

ideology of a transitional phase was

based. However, probably the most

significant project of this

transitional and teleological regime

was the planning and building of New

Belgrade —both the symbol of the new

Yugoslavia and the model for its

building. As an “ideological centre

of brotherhood and unity” – as this

major project was first called by

the Yugoslav political elites — New

Belgrade was systematically included

in the discourse of transition as

part of a complex ideological

narrative implying the introduction

of a number of differences —

differences relative to the recent

past that established a normative

and value framework for the

realization of the projected future.

Since the first plans for building a

new city and urban regulation, New

Belgrade was considered instrumental

in the process of constructing the

imagined identity regardless of

whether it was aimed to create the

image of the capital of the new

Yugoslavia, or the framework for the

functioning of a contemporary

democratic society. significantly determined and

confirmed the contents on which the

ideology of a transitional phase was

based. However, probably the most

significant project of this

transitional and teleological regime

was the planning and building of New

Belgrade —both the symbol of the new

Yugoslavia and the model for its

building. As an “ideological centre

of brotherhood and unity” – as this

major project was first called by

the Yugoslav political elites — New

Belgrade was systematically included

in the discourse of transition as

part of a complex ideological

narrative implying the introduction

of a number of differences —

differences relative to the recent

past that established a normative

and value framework for the

realization of the projected future.

Since the first plans for building a

new city and urban regulation, New

Belgrade was considered instrumental

in the process of constructing the

imagined identity regardless of

whether it was aimed to create the

image of the capital of the new

Yugoslavia, or the framework for the

functioning of a contemporary

democratic society.

That new identity

was based on the established

postulates of modernist architecture

and urban planning. The adoption,

reinterpretation and specific

Yugoslavianization of these models

took place in the context of

legitimizing a transitional

situation and generated numerous

manifestation forms most of which

being formally linked to the

architectural paradigm of high

modernism. The continuous exchange

of ideas and plans for New Belgrade,

analogous to the adoption of ever

new Yugoslav constitutions, was

aimed at presenting the proclaimed

values and searching for new paths

for the “architecture of the

Yugoslav peoples”. The fact that the

ideological concepts of Yugoslav

society were constantly redefined

and made increasingly intricate, can

to some extent explain the

phenomenon of the conceptual

inconsistency and incompleteness of

New Belgrade. On the other hand, its

architectural and urban structures

served as a representative example

of the transformed environment and

confirmation of the correctness of

the movement and progress of the

entire society.

However, not only

numerous architectural and urban

planning competitions of the 1960s

and 1970s – it is advisable to view

them from the perspective of the

model of “utopian realism”, as

defined by Anthony Giddens – but

also a significant part of the

representative architectural

production of the time also

functioned using the same

ideological register. The humanistic

ideals of the liberated man and free

society, as the most significant

value incorporated into the

ideological system of postwar

Yugoslavia, was confirmed in the

discourses of architecture,

primarily within the scope of the

thesis about antidogmatism, not only

as the most valuable source of

architectural creation, but also as

the fundamental social value

exceeding the bounds of cultural

practices. Or, more precisely, with

the interpretation and ideological

instrumentalization of the

architecture of modernism in

Yugoslavia after 1948 there began a

long and all-pervading process of

building and cultivating

antidogmatism, which was reflected

in shifting away from rigid

functionalism, on the one side, and

formalism, on the other side. Over

time, the recognizable criteria that

systemically linked architecture to

a broader ideological framework

became entrenched in architectural

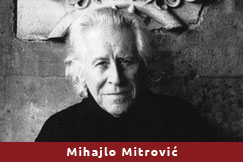

discourse. The most significant

criterion was the establishment of a

causal link between ethical and

aesthetic values, on the one side,

and the freedom of man, on the other

side, as contrasted to something

that was called an “intertia of

clerical mentality” by Mihajlo

Mitrović, one of the protagonists of

Serbian and Yugoslav architecture.

By cultivating a specific discourse

of mediation between aesthetics and

politics, which basically repeated

the pattern in which Yugoslavia’s

overall politics and culture

functioned at that time, this

prolific architect was just one of

the many fighters for creativity

freedom and non-orthodox modernist

architecture having an exceptional

ideological resonance in their own

historical context. criterion was the establishment of a

causal link between ethical and

aesthetic values, on the one side,

and the freedom of man, on the other

side, as contrasted to something

that was called an “intertia of

clerical mentality” by Mihajlo

Mitrović, one of the protagonists of

Serbian and Yugoslav architecture.

By cultivating a specific discourse

of mediation between aesthetics and

politics, which basically repeated

the pattern in which Yugoslavia’s

overall politics and culture

functioned at that time, this

prolific architect was just one of

the many fighters for creativity

freedom and non-orthodox modernist

architecture having an exceptional

ideological resonance in their own

historical context.

Thus, in

Yugoslavia’s public space modernist

architecture was assigned to

materialize the hardly attainable

goal of freedom, autonomy and

shifting away from canonical

thinking and acting, lying at the

core of the idea about Yugoslavia’s

“socialist democracy”. Over time,

despite all stylistic, morphological

and structural differences relying

on the global trend of redefining

the “international language” of

modern architecture, Yugoslav

architecture of so-called high

modernism in the 1960s and 1970s

became the signifier of the

desirable social values and

constituent part of political

discourse. It participated in a

general revolt against

depersonalization, impersonalness

and standardization – at the same

time when the leadership of

Yugoslavia, “one of the most open

countries” — as once emphasized by

historian Branko Petranović —

promoted the same messages in public

discourse, thus reaffirming the

highest values of a self-management

socialist society. In that sense,

antidogmatism became both the poetic

quality of architecture and contents

of a political ideology. On the

other hand, subjectivism in

architecture was crucial for the

legitimization of the political

course of socialist Yugoslavia and

important factor in the cultivation

of diversity (national, ethnic,

cultural, regional), as the

sacrosanct value of Yugoslav

socialism. In socialist Yugoslavia,

as noted by architect Ivan Štraus in

1991, at the time when the rigor

mortis of the state of the “Yugoslav

peoples and nationalities” already

occurred, architecture began to be

viewed in new ways, in accordance

with increasing democratic freedoms,

while at the same time clearly

highlighting individual views. important factor in the cultivation

of diversity (national, ethnic,

cultural, regional), as the

sacrosanct value of Yugoslav

socialism. In socialist Yugoslavia,

as noted by architect Ivan Štraus in

1991, at the time when the rigor

mortis of the state of the “Yugoslav

peoples and nationalities” already

occurred, architecture began to be

viewed in new ways, in accordance

with increasing democratic freedoms,

while at the same time clearly

highlighting individual views.

This testifies

that mere utilitarianism in

architectural poetics was

transcended by the construction of

an aestheticized world as the

projection of the origin of the

movement of the entire society. In a

subtle ideological shift from

functional to nonutilitarian,

architecture was a striking example

of transitoriness, changeability and

mobility, as the central social

values. Despite the functional

requirements on which it was based,

its emergence as an aesthetic

phenomenon understandably had both

ethical and political dimensions.

From that perspective, the

architecture of modernism

represented quite an autonomous

value system in accordance with the

basic ideas of modern art, but its

relationship with the social context

was by no means excluded. On the

contrary, the idea of autonomous

architecture with individualism at

its root as the most important

characteristic of something named

“socialist aestheticism” first in

the criticism of Yugoslav culture

and then in historiography, was part

of the process of spatializing the

ideological premises of socialist

self-management: free society,

plurality of thought and action, and

insistence on cultural diversity.

***

If the historical

experience of Yugoslav modernism is

viewed in its historical context,

outside the tradition of great

architectural narratives, and if it

is critically evaluated relative to

the idea about the autonomy of

modern art, it testifies not only

that architecture cannot be

considered value-neutral, but that

we must also understand it as a

basically ideological practice.

Namely, the historicization of the

architecture of modernism in the

first and second Yugoslavia can

confirm not only the general

theoretical premises of culture as

an ideological system in which

cultural forms and processes obtain

politically instrumental meanings,

but also much more than that. It

seems that a new reading of all that

was written and thought about the

architecture of modernism by its

contemporaries, including its own

ideological horizon trends, as well

as a careful interpretation of the

form of its presence in public

space, can help us open the new

views on the whole Yugoslav past. In

that landscape, the contours of the

architecture of modernism in

Yugoslavia will also be clearer and

less obscured by double resistance,

which still hinders its

consideration — resistence from the

discipline of architectural history,

including its obsession with

stylistic, formal and theoretical

genealogies and typologies, and its

unwillingness to offer a rational

interpretation of the Yugoslav

experience. A new image can help

that Yugoslav architecture is

understood not as a phenomenon

separated from its historical

context, or just a form of

legitimation of political ideas and

regimes, but as the constituent part

of the world of ideas on which the

diverse ideological foundations of

the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and its

socialist successor state were laid.

|